Oakley Hall's Warlock

Warlock screens Sunday, February 10 as part of Film Comment Selects, with introduction by Geoffrey O’Brien, former editor of Library of America.

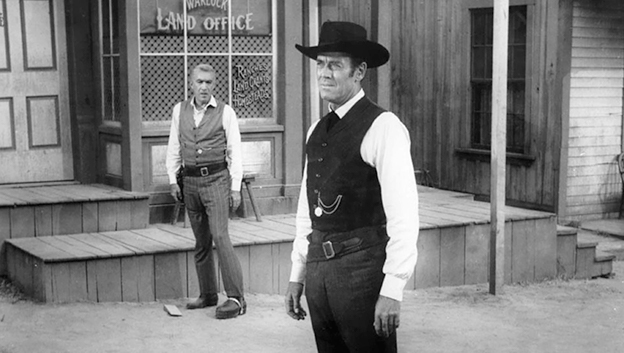

In Edward Dmytryk’s 1959 CinemaScope Western, the mining town of Warlock is at the mercy of a band of rogue cowboys, until citizens engage the sharpshooting services of Clay Blaisedell (Henry Fonda), accompanied by right-hand man Tom Morgan (Anthony Quinn). Adapted from the razor-sharp 1958 novel by Oakley Hall, Dmytryk’s film becomes a roiling panorama of competing drives and moral ambiguities, epitomized by Richard Widmark’s tormented Johnny Gannon. Warlock costars Dorothy Malone and DeForest Kelley, and was shot by Joe McDonald (My Darling Clementine, Pickup on South Street).

Thomas Pynchon pronounced Oakley’s original book (a Pulitzer finalist), “one of our best American novels,” which “restored to the myth of Tombstone its full, mortal, blooded humanity.” Robert Stone, in his introduction to the 2006 New York Review Books reprint of the novel, writes that, “In the evocatively named town of Warlock (shades of Young Goodman Brown) the Apaches kill and die and are followed by the Mexicans who slaughter the gringo cowboys and are killed by them. The US Cavalry having helped decimate the Indians and Mexicans are now used against white labor by mine owners. The murderous cattle barons who made their own law in the Rattlesnake Valley are driven down and out. America, aspiring toward her self-generated pseudo-myths, remains a prisoner of her deepest true ones.”

Read an excerpt from Hall’s novel, reprinted below with the kind permission of NYRB.

Chapter 20: Gannon Has a Nightmare

The town of Warlock is flourishing. Its recently appointed marshal, Clay Blaisedell, has driven out the cowboy gangs and cattle rustlers that hitherto marred its name. Among those expelled from the frontier town is Abe McQuown, whose gang once ran rampant. Two brothers, John and Billy Gannon, find themselves cleft between these two forces: John—also referred to as “Bud” or simply “Gannon”—hopes to redeem his image by accepting the position of deputy sheriff; Billy, however, remains with McQuown.

It is a dream, he told himself; it is only a dream. Sweating, naked, daubed with mud, he crouched behind a crag upon the canyon wall and watched against the curtain of his memory the sandy river bottom of Rattlesnake Canyon, listening in the waiting silence to the pad of hoof irons in the sand and the sharper, urgent sound as a hoof struck stone, and, nearer, the musical clink of harness, and nearer still, voices soft-mouthed with Spanish; his heart turning over on itself as the first one came around the far bend upon a narrow-faced white horse, looking very tall at first in his high, peaked sombrero, but small, compact, brown, watchful-eyed, with pointed mustachios, behind him another and another, some with striped serapes hung over their shoulders and all with rifles carried underarm; seven, eight, and more and more, until there were seventeen in all, and Abe’s Colt crashed the signal. The echo was instantaneous and continuous. Smoke drifted up from all around the canyon where the other mud-daubed figures were concealed, and it was as though an invisible flash flood had in that instant swept down the canyon: horses reared and screamed, swept backward in the flood, and died; men were thrown tumbling, a rifle flung up in a wide arc turning end over end with weird slowness, and there were gobbling Apache cries mixed with the screams of dying men. There was the white horse lying on the reddening sand, there was the leader in his high, silver-chased hat crawling in the stream; then the hat gone, then a part of his head gone, and he lay still in the channel with his jacket shiny and bloated in the water that ran red over him. And now the half-naked, muddy Apache figures stood all around the canyon, yelling as they fired into the mass of dying men and horses below them, the faces magnified and slowly revolving before his eyes—Abe, and Pony and Calhoun and Wash and Chet, and on the far side Billy and Jack Cade, Whitby and Friendly, Mitchell, Harrison, and Hennessey.

And at the end there came the Mexican running and scrambling up the steep bank toward him, hatless, screaming hoarsely, brown eyes huge and rimmed with white like those of a terrified stallion, and the long gleam of the six-shooter in his hand, slipping and sliding but coming with unbelievable rapidity up the canyonside toward him, John Gannon. He changed as he came. Now he came more slowly; now it was a tall, black-hatted figure walking toward him through the dust, slow-striding with the massive and ponderous dignity not of retribution but of justice, with great eyes fixed on him, John Gannon, like ropes securing him, as he cried out and snatched in helpless weakness at his sides, and died screaming mercy, screaming acceptance, screaming protest in the clamorous and horrible silence.

It is only a dream, he told himself, calmly; it is only the dream. But there was another reverberating clap of a shot still. He died again, in peace, and waked with a jolt, as though he had fallen. There was another knock in the darkness of his room.

“Who is it?” he called.

“It’s me, Bud,” came a whisper. He swung off his cot in his underwear and went to open the door. Billy came in, stealthily. A little moonlight entered through the window, and Billy was visible as he moved past it, wearing a jacket and jeans, his hatbrim pulled low over his face.

“What are you doing in town?”

“Come to see you, Bud.” Billy laughed shakily. “Sneaked in. Tomorrow I don’t sneak in.”

Billy took off his hat and flung it down on the table. He swung the chair around and sat down facing Gannon over its back. The moonlight was white as mother-of-pearl on Billy’s face.

Gannon slumped down on the edge of the bed, shivering. “Just you?” he said.

“Pony and Luke and me. Calhoun weaseled.”

“Why Pony?”

“What do you mean, why Pony?”

“He hasn’t any right to come—he was at the stage. Was Luke in on it, or not?”

“Not,” Billy said shortly. Then he said, “It doesn’t matter who was at the stage or not.”

“No, it doesn’t matter now. They were lied off and you with them, so it is too late to tell the truth.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” Billy said. Gannon could see that he was shivering too. “But I have got to do it, Bud.”

“Got to get yourself killed?” He had not meant to speak so harshly. “Don’t be so damned sure about that!”

“Got to kill Blaisedell then?”

“Well, somebody’s got to, for Christ’s sake!”

Gannon closed his eyes. It might be the last time he saw Billy; probably it was; he knew it was. And they would wrangle meaninglessly over who was the son of a bitch, Blaisedell or Abe McQuown. It seemed to him that if he was any kind of man at all he could let Billy have his way tonight.

“Listen, Bud!” Billy said. “I know what you think of Abe.”

“Let’s not talk about it, Billy. It’s no good.”

“No, listen. I mean, what is different about him? He goes along the way he always did that used to be all right with everybody, but everybody’s got down on him. He gets blamed for everything! He—”

“Like the Apaches used to,” he said, and despised himself for saying it.

Billy said in a husky voice, “I know that was a piss-poor thing. Do you think I liked that? But you make too much of it.”

“I know I do.”

“Well, like the Paches; surely,” Billy went on. “But you know what it’s like all around here. Every son with a true-bill out against him ends up here, and he has got to eat so he swings a wide loop or tries to agent a coach or something. And Abe gets blamed for it all! But you know damned well—“

“Billy, you are not coming in tomorrow because of Abe.”

“Coming in because a man has to stand up and be a man!” Billy said. “That suit you? Because it is a free country and sons of bitches like Blaisedell is trying to make it not.”

He looked at Billy’s taut, proud young face with the glaze of moonlight on it, and slowly lowered his head and massaged his own face with his hands. Billy’s voice had been filled with righteousness and it tore him to hear it, and to hear Abe McQuown behind it furnishing the words that were true enough when Billy spoke them and yet were lies because they came from Abe McQuown.

“But I guess you don’t think that way,” Billy said.

Gannon shook his head.

“He is after Abe,” Billy went on. “He is after all of us! A person can’t stand it when there is somebody on the prod for him all the time. Trying to run him out or kill him. A man has got to stand up and—“

“Billy, Blaisedell saved your life when he backed off that lynch party. And Pony’s, and Cal’s, and maybe mine. And he could have killed Curley that night in the Glass Slipper, if that was what he was after. And you too. And Abe.”

“He just wanted to look good, was all. And us to look bad. I know how it would’ve been if he’d had us alone and nobody to see.”

“What if he kills you tomorrow?” he whispered.

“I’ve got to die some day, Christ’s sake!” Billy said, with pitiful bravado. “Anyway he won’t. I figure Pony and Luke can stand off Morgan and Carl, or that Murch or whoever he’s got to back him. I figure I can outpull him and outshoot him too. I’m not scared of him!”

“What if he kills you?” he said again.

“You keep saying that! You’re trying to scare me. You want me to run from him?”

“Yes,” he said, and Billy snorted. “Billy—“ he said, but he knew it was useless even before he said it. “You weren’t at the stage and you shot Ted Phlater in self-defense, but not the way it looked in court. Billy, I can’t see you die a damned fool. I—“

“Don’t you ever say a thing to anybody about any of that,” Billy said coldly. “I am with them, whatever way it happened. That is gone past now. You hear? That’s all I ask of you, Bud.”

That hurt him, as part of the long hurt that Billy had never been able to think much of him. He sat shivering on the edge of the bed, and now, when he didn’t look at his brother, Billy seemed to him already to have become just another name on Blaisedell’s score, and just another mound on Boot Hill marked with one of Dick Maples’ crosses. With horror he looked back to Billy’s moonlit face.

“Billy, I don’t mean it any way and you don’t have to say if you don’t want to, but—do you want to die?”

Billy was silent for a long time. He leaned back and his face was lost in shadow. Then he laughed scornfully, and one of his bootheels thumped on the floor. But his voice was not scornful: “No, I am afraid of dying as any man, I guess, Bud.” He rose abruptly. “Well, I’ll be going. Pony and Luke are camped out in the malapai a way.” He started toward the door, pushing his hat down hard on his head.

“Sleep here if you want. I’m not going to try to argue with you any more. I know you are going to do what you are set on doing.”

“Surely am,” Billy said. He sounded childishly pleased. “No, I’ll go on out there, I guess. Thanks.” At the door he said, “Going to wish me luck?”

Gannon didn’t answer.

“Or Blaisedell?” Billy said.

“Not him because you are my brother. Not you because you are wrong.”

“Thanks.” Billy pulled the door open.

“Wait,” he said, getting to his feet. “Billy—I know if somebody shot me down you would take after them. I guess I had better tell you I won’t do it. Because you are wrong.”

“I don’t expect anything of you,” Billy said, and was gone. He left the door open behind him.

Gannon crossed to the door. He couldn’t see Billy in the darkness of the hallway, but after a moment he heard the slow, stealthy descent of bootheels in the stairwell. He waited in the darkness until the sounds had ceased, and then he closed the door and returned to his cot, where he flung himself down with his face buried in the pillow and grief tearing at his mind like a dagger.