Dispatch: Karlovy Vary 2019

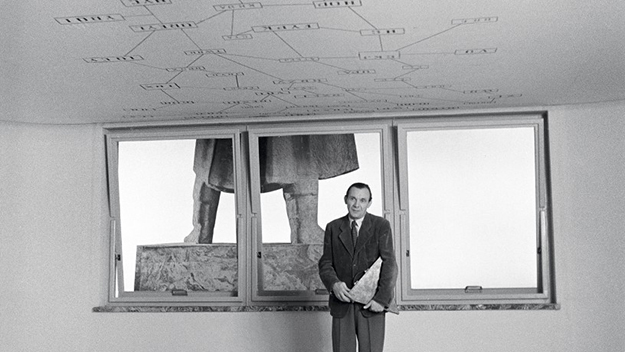

The Cremator (Juraj Herz, 1969)

The old specter is haunting Europe again. I arrived at Karlovy Vary for its film festival after a short stay in the precincts of Exarcheia, Athens, where the familiar hammer and sickle shares space on walls with the anarchist red-and-black, and dissidents fight it out nightly with a police force who, per some sources, has been infiltrated extensively by the far-right Golden Dawn Party. Political schisms once thought left in the prior century are alive and well in Europe as at home, and while not caught up in the same outright turmoil the city of Karlovy Vary itself still bears the physical traces of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic regime. A picturesque spa town founded in the 14th century that’s been frequented through the years by such A-listers as Peter the Great and Goethe, Karlovy Vary during Czechoslovakia’s Communist period was a popular destination for Party brass from near and far—the small local airport still operates only two weekly flights, to and from Moscow. For years, between 1959 and 1993, the festival was a biennial, switching off with the Moscow International Film Festival, and the main festival facility, the Thermal Springs Colonnade, represents this Habsburg jewel box of a city’s most visible concession to the sterner Soviet style, 19 stories of frowsily Functionalist reinforced concrete containing a hotel and multiple screening rooms.

Such thoughts as these were encouraged by “Liberated,” a sidebar of films produced in Czechoslovakia in the transitional years of 1989-92, that ran through this year’s Karlovy Vary—among them Věra Chytilová’s The Inheritance and Juraj Jakubisko’s It’s Better to Be Wealthy and Healthy Than Poor and Ill (both 1992). The program was tagged, loosely, to the 30th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, the series of nonviolent demonstrations that led, in the final months of 1989, to the end of one-party rule in then-Czechoslovakia and the election of writer and dissident Václav Havel as the new Czechoslovak Republic’s president.

Per the catalog essay by Karel Och, Liberated was curated as a celebration of “the demise of the odious Bolsheviks’ totalitarian hegemony,” but if unalloyed nostalgia for the old days was little in evidence in the films of the program, the perspective on the wide-open new world of liberal democracy and capitalism unbound that they present is not always unequivocally positive. In Chytilová’s loud, lewd morality tale, Boleslav Polívka plays a low-born lummox-turned-nouveau riche Prometheus unbound, boorishly browbeating his newfound inferiors, who’ve no choice but to kowtow before the new cult of wealth. And already in It’s Better to Be Wealthy and Healthy Than Poor and Ill, one finds a deep ambivalence towards the emerging capitalist (dis)order, seen as quickly making mercenaries of idealists. Jakubisko’s tender, melancholy film follows the comic misadventures of brunette Nona (Deana Jakubisková-Horváthová), who is a Slovak political dissident, and blonde Czech Moravian Ester (Dagmar Havlová), the former mistress of a secret police agent. Jilted by their men and set adrift by larger historical ructions, the two are thrown together by circumstance and forced to live by their wits, becoming buccaneer entrepreneurs in the Wild East who, in the course of the madcap movie, gain and lose fortunes. (The movie was advertised abroad as a Czechoslovak Thelma & Louise, but a comparison to Chytilová’s 1966 Daisies is more apt.) Whatever the system, it seems, women wind up with the shit end of the stick—but here are seen to abide by virtue of a very touching sense of solidarity. It’s Better to Be Wealthy and Healthy Than Poor and Ill concludes with Nona and Ester reunited after a falling out, though by the time of its release the Czech and Slovak Republics were already on their way to amicably announcing irreconcilable differences, parting ways mere months after the public premiere of Jakubisko’s film.

It’s Better to Be Wealthy and Healthy Than Poor and Ill (Juraj Jakubisko, 1992)

As much as the thrill of freedom, one could also find in the Liberated series the ruefulness that marks It’s Better to Be Wealthy and Healthy Than Poor and Ill—that sense of opportunities likely to be missed. Introducing his 1991 cult film Smoke, director Tomás Vorel bemoaned the post–Velvet Revolution dismantling of the nationalized film industry as a mistake. (Vorel also discussed his creative association with Havel, who played the president in Vorel’s 1996 film The Stone Bridge.) In the days after the festival, visiting the National Gallery in Prague at the Trade Fair Palace, I spent some time with the work of Adéla Babanová, including a projection of her 38-minute 2018 Neptun, an ingenious simulacrum that mixes together original shot-on-35mm footage with actual newsreel documentation of the “discovery” of Nazi documents sunk in a Bohemian lake in 1964—later revealed to be a plant by the Czechoslovak StB state police—undercutting the indexical integrity of the filmed image in laying out a tale of disinformation. Per the didactic wall text, the work reflects how “ideological mechanisms of manipulation and the propaganda use of disinformation seem invisible phenomena applied to and influencing mass consciousness as much in the totalitarian past as in the democratic pluralistic present.” In other words: Meet the new boss, same as the old.

Some instances of the film art produced under the previous regime could be viewed in Karlovy Vary’s “Out of the Past” program, dedicated to restorations and revivals. A highlight of one kind of export this year was a screening of 1945 Poverty Row immortal Detour, whose director, Edgar G. Ulmer, was born in Olomouc, in the present-day Czech Republic. Projected in the ornate baroque Municipal Theatre, decorated by Gustav Klimt and brother Ernest, it was as striking an instance of contrast between setting and product, a vigorous, rude charcoal etching in a grandiosely gilded frame.

Also of note were two films made closer to home by Slovak filmmakers associated with the largely Prague-centered Czechoslovak New Wave: Peter Solan’s The Barnabáš Kos Case (1965) and Juraj Herz’s The Cremator (1969). The former, based on a short story by Slovak writer Peter Karvaš, is an absurdist satire of bureaucratic meddling and rewarded mediocrity starring Josef Kemr in the title role as a middle-aged triangle player in the national symphony orchestra who, quite without warning, is elevated to the position of the orchestra’s creative director. Cleverly engineered sequence shots work to establish Kos as a tiny cog within the grand orchestral mechanism, but upon his promotion absolute power proves to corrupt absolutely, and the formerly meek Kos is soon reborn as an activist executive, prattling airily about Dvořák’s “feel for the triangle,” commissioning a desperate composer to write a triangle-heavy composition for world premiere, and visiting a forge to have a massive triangle made for his clangorous, catastrophic solo.

The Barnabáš Kos Case (Peter Solan, 1965)

The Barnabáš Kos Case’s pointed parallels to regime incompetence in promoting unqualified yes-men couldn’t be clearer, but the relative freedom in terms of subject matter that Solan enjoyed in the mid-’60s wouldn’t last for long—hence the banning of Herz’s The Cremator, whose rumination on rising despotism in the ’30s sat uncomfortably with the administration of its own era. Where Solan achieves distortions of scale largely through set design, Herz’s film does so through the queasy, leering, funhouse-mirror cinematography of Stanislav Milota—scholar Daniel Bird’s comparison to the style of Alexei German is an apt one. Herz’s approach is to thrust us into the troubled headspace of Karel Kopfrkingl (a pudgy, clammy Rudolf Hrušínský), a mortician working in prewar Prague whose proselytization for the merits of cremation gradually takes on a crackpot religious fervor as his obsession with the Tibetan Book of the Dead is intertwined with the fascist rhetoric that’s becoming everyday parlor chat. He begins to take his duty as liberator of trapped souls so seriously that he sees no reason to wait for people to die in the natural course of events before liberating them. The significance of Kopfrkingl’s method of eliminating corpses needs little elaboration; Herz, it should be noted, was a Jewish survivor of the Ravensbrück camp, and as such perhaps uniquely qualified to contemplate the executioner’s mentality.

The Cremator, which will have a weeklong New York run at Metrograph starting on August 7, part of a touring Herz retrospective, was a film born in the afterglow of the Prague Spring, and wouldn’t re-emerge into distribution for 30 years, with the Velvet Revolution, in the wake of which even seemingly innocuous pop films took on a political dimension. Let’s All Sing Around (1990) doesn’t correspond to the usual idea of a film tract—it’s a summer camp movie, which freely borrows tropes developed in Meatballs (1979), Porky’s (1981), and the like. The essential difference here is that Trojan’s film, a period piece set at an unspecified date in the not-too-distant past, takes place in a camp affiliated with the Pioneer Organization of the Socialist Youth Union—the equivalent to the Boy Scout organization in communist Czechoslovakia. The proceedings are short on ideological drills, long on the usual stuff of teen comedies—painful horniness, locker room peeping, etc.—with director Ondřej Trojan working in some ingenious sight gags, including shot puts launched into the stratosphere and a vain attempt to re-root a live tree harvested for firewood, expressly forbidden by Party ukase. The evening’s biggest laugh, however, came at the tail end of a scene involving an interminable hike, when the campers path is suddenly crossed by a fleeing refugee with suitcase in hand high-tailing it across a bog with uniformed border patrol officers two paces behind, hot on his heels.

Let’s All Sing Around (Ondřej Trojan, 1990)

While Solan and Herz stayed on after Soviet tanks arrived to put an end to the Prague Spring in summer of 1968, emigration was the path taken by many of the brightest lights of the Czechoslovak New Wave, including Jan Němec, who’d effectively been blocked from making films in his native country after ’68, shortly after he’d blown onto the scene with cage-rattling works Diamonds of the Night (1964) and A Report on the Party and the Guests (1966). The Liberated program included Němec’s homecoming comeback film, made following a lengthy exile period spent in part videotaping weddings—perhaps not coincidentally, one of the business ventures of the women in It’s Better to Be Wealthy and Healthy Than Poor and Ill. Němec’s The Flames of Royal Love (1990) is a veritable explosion of bottled-up filmmaking energy, adapted from Czech philosopher and proto-surrealist writer Ladislav Klíma’s novella The Sufferings of Prince Sternenhoch, published posthumously in 1928, and long a dream project for the director. A tawdry, raffish fairy tale centering on the hypergamous marriage between a cleaning woman (Ivana Chýlková) and a prince (rock star Vilém Čok) that quickly descends into a grudgeful war of wills, its content is very “Once upon a time…” but its setting is distinctly contemporary, with architect Václav Aulický’s rather infamous Žižkov Television Tower, a real-life science fiction monument still under construction at the time of filming, playing the royal residence.

Němec, like Herz possessed of a pronounced black comic streak, created the decadent and deranged monarchial mishegas of The Flames of Royal Love in collaboration with consulting artist Michael Rittstein, turning contemporary Prague into a loose, louche world of nauseous glut and clutter. Born 1949, Rittsteinhad came to prominence during the ’80s through a series of large canvases defined by Baroque exorbitance; searing, unnatural colors; painfully distorted figures; and, often, a sense of domestic stultification. With the likes of Jiří Sopko and Jiří Načeradský, Rittstein has sometimes been identified as part of a mini-movement, the so-called Česká groteska or Czech grotesque school, often framed as a response to the stultifying political climate of Czechoslovakia in the ’80s.

Something like a “Czech grotesque” school has its own storied history in the cinema, as the examples of Chytilová, Němec, and Herz profusely show, though the living links to that tradition are disappearing fast. Chytilová died in 2014, Němec in 2016, Herz in 2018, and Czech or Slovak artists possessed of their particular perspective, having both predated and outlived the Iron Curtain, so-called, cannot be replaced. What remains are their visions of excess, inundated with the obscenities of the system, whatever the system or regime of the moment might happen to be.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.