Deep Focus: Unsane

Explanatory ads and teasers, be damned! Feel relieved if all you bring away from them is portraits of the sensational Claire Foy in psychic torment and physical jeopardy. To give away anything else about Unsane is unfair.

With equal splashes of wit and gore, this cool, nasty little thriller fearlessly exploits up-to-date strains of social and sexual paranoia. It also eviscerates infuriating bureaucratese, circa now, whether practiced by complacent law enforcers, a sexist bank executive, or manipulative hospital personnel.

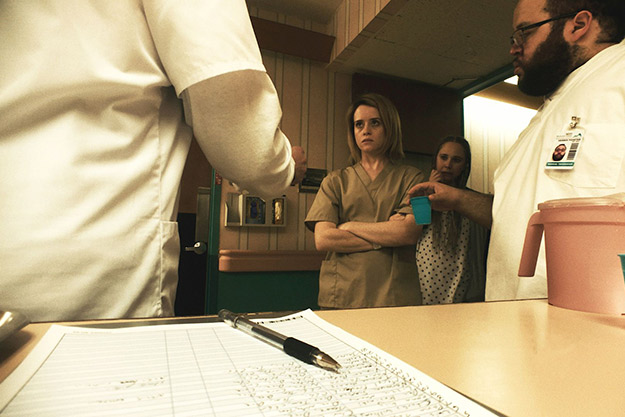

Under his cinematographer pseudonym (Peter Andrews), Steven Soderbergh shot this movie swiftly, on an iPhone, capturing his performers’ every twitch and pose and near-subliminal shift of expression. And under his editing pseudonym (Mary Ann Bernard), he cut the film like a psychological steeplechase, complete with messy mud-and-blood splatters and spills. Neither overheated and over-calculated, like Paul Verhoeven’s Elle, nor frigid and laminated, like David Fincher’s Gone Girl, it resembles Sam Fuller’s Shock Corridor mixed with elements of Neil Jordan’s scandalously ignored In Dreams. It’s a nightmare with a heroine who has her eyes wide open.

Foy’s Sawyer Valentini is a super-sharp banking analyst who doesn’t suffer fools gladly—or at all. Afflicted with the hyper-vigilance, anxiety attacks, and flashback/hallucinations we associate with PTSD, as well as trust and intimacy problems, she’s one more woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

She’s ferociously smart and often ruthlessly clear-headed, especially after she mistakenly commits herself to a mental hospital. Think back to Broadcast News, when Albert Brooks tells Holly Hunter, “It must be nice . . . to always think you’re the smartest person in the room.” Hunter replies, “No, it’s awful.” In or out of the institution, that’s Sawyer’s plight in Unsane. She’s a take-no-prisoners character who starts out in a metaphoric psychological prison and winds up in a literal one.

Elle earned so much critical good will partly because it’s extra-thrilling to see any genre-movie hero these days who doesn’t focus on charming his or her peers and the audience. That goes double for Unsane. Foy’s ruthlessly unsentimental and nimble, quick-witted performance makes her perfect casting for punk hacker Lisbeth Salander in the forthcoming Girl in the Spider’s Web.

One thing Foy’s banking analyst has over Isabelle Huppert’s video-game tycoon in Elle is that you believe Foy is good at her job. We meet her as she briskly tells a dissatisfied client, over the phone, that the work she’s done is correct: another analyst might provide different results, but they would be wrong. To Sawyer, the customer is not always right. Nor is the sweet co-worker Jill (Sarah Stiles) who thinks in clichés, like the one about catching more bees with honey than with vinegar.

Soderbergh and his screenwriters, Jonathan Bernstein and James Greer, sustain their first-rate office satire when Sawyer’s boss (Marc Kudisch) offers her a chance to fly from their base in Pennsylvania to a banking conference in New Orleans and room with him for two nights at the Hyatt Regency. Reacting to her keeping a distance and her deadpan hesitation with several series of “good, good, good, ” he’s risibly smarmy. No wonder she dissembles to her mom (Amy Irving) back in Boston how well she’s doing in Pennsylvania. It makes sense that she’d want to rush into a computer-generated date.

To give away as little as possible (and far less than the trailer), let’s just say that what happens next drives her to seek help at the Highland Creek Behavioral Center in a remote setting beyond city limits. Unbeknownst to Sawyer, it’s a mental health version of a Medicaid mill. Its staff finds ways to hold patients for as long as their insurance pays—usually a day to a week for observation, a month for opioid treatment.

It’s astonishing to me that some advance reviews complained that Sawyer’s character lacks depth. Part of what makes this film so gripping is that we know she needs “help,” not incarceration. When she lets her hair down with a Highland Creek “counselor” (the superbly faux-compassionate Myra Lucretia Taylor), the dark revelations about her life are heart-stopping. They become heartbreaking when we realize that she can talk to no one else about them, including her mother. Sawyer signing her own admission papers is poignant as well as terrifying because she’s trying to overcome her OCD by not reading the fine print.

As the action gets graphic and bloody, what keeps us rooting for Sawyer is not only her position as a trapped innocent but also the quicksilver complexity Foy brings to every aspect of her performance. She’s alternately manipulative and emotionally naked, wily and naïve, snobbish and empathetic—or so skilled at analyzing other people that she can pass for empathetic.

In these perilous times, it’s fitting that the semi-crazy Sawyer and an investigative journalist are the characters most capable of independent thought and honest feeling. Nurses and orderlies merely cling to their jobs. We recognize the doctor with the boardroom manner, the business manager who seconds as a PR expert. Even Sawyer’s mother’s lawyers and the slobby local cops fall back on rules, regs, and jargon, or keeping their paperwork in order.

Soderbergh’s iPhone shooting is no gimmick. The disorienting effect he achieves with a fish-eye lens when Sawyer is over-drugged is actually the least interesting thing about it. First, without ostentation, the iPhone enables him to get the most out of actors in close quarters. She faces off with her most dreaded antagonist in a padded cell that seems to close in on her like the walls in “The Pit or the Pendulum.” Her targeted vision cuts the ward and lunchroom into sections where she either bonds with an opioid addict (the immensely amiable SNL veteran Jay Pharoah) or jousts with a lowdown long-term patient (Juno Temple, in a hair-raising display of guttural bravura).

Just as important, Soderbergh uses his phone to conjure a natural kind of unnatural lighting. Things get creepy when you notice that the panel lamps in some inner corridors are one-on, one-off. At night, the hospital’s shadows grow malignantly ominous. If, like me, you find the puky “palliative” colors and lighting of medical spaces unsoothing, you’ll experience this film’s clinical ambiance like bedbugs crawling up your back.

Foy’s talent illuminates this whole clever horror show. When another British TV favorite, Benedict Cumberbatch, played Doctor Strange, his acting was apt and bright but his generic American accent blunted his usual flair. The opposite happens here with Foy. She makes Middle Atlantic cadences seem as keen and flexible as a Swiss Army Knife.

In every scene, you see her work separate vocal blades in quick succession. She can be unctuous and flattering to the head nurse (Polly McKie) when she still thinks she can talk her way out of trouble, then turn bristling and abrasive as soon as she gets her hand on a phone.

Foy’s frankness emerges in fierce bursts of jet-black humor. She brings down the house when the doctor threatens her with solitary confinement, telling him: “Take me there right fucking now.” But she isn’t afraid to play the mean-girl putdown artist when she lets the obstreperous Temple know that she does feel too good to talk to her, “you fucking mental patient.”

In last year’s sorely overlooked Breathe, Foy brilliantly used the same split-second control over split-level emotions that she mastered throughout The Crown to play Diana Cavendish, the wife of paralyzed polio survivor and pioneer “responaut” Robin Cavendish. With ease, Foy brought off precarious scenes in which Diana felt genuine joy or relief yet still had to act it out for Robin’s benefit. She brings a similar authenticity and heightening to Sawyer. Even after learning clinical details about her past, including her father’s death when she was 15, we never ultimately learn what makes Sawyer run.

Foy’s performance is so rich that she turns her character’s ambiguous volatility into a virtue. In The Crown she became acting royalty. In Unsane she’s a once and future scream queen.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and a contributor to the Criterion Collection.