Deep Focus: The Martian

Ridley Scott’s improbably charming and engrossing The Martian, with Matt Damon in the title role, could have been called The American. The director told The Los Angeles Times last month: “In a funny kind of way, Matt is almost the perfect representative of the American. He’s fair, he’s sweet, he’s firm, he’s intelligent, and he’s a very can-do kind of guy.”

This Yankee Doodle Dandy decency permeates Damon’s characterization of Mark Watney, a botanist in a six-person NASA space crew who’s been taking soil samples on Mars. Wounded during a sandstorm, left for dead by his crewmates, he gamely performs his own emergency surgery and then sets smartly about creating a new food supply. Nothing comes too easily. Even generating water causes fiery blowback (he does it by burning the chemical compound hydrazine). Whenever a setback knocks his chin to the ground, Mark picks himself up, brushes himself off, and starts all over again. William Dean Howells once quipped: “What the American public wants is a tragedy with a happy ending.” The Martian is like an upbeat rendering of the Myth of Sisyphus. Even its repetitions are surprising, because you don’t expect a mainstream adventure movie to admit so many complications.

This film rouses cheers because its hopefulness is earned. The Martian doesn’t contain a single up-with-people bromide, and it never sacrifices tension for jokes or sentimental gestures. Mark’s refusal to surrender in the fight to survive only adds to the suspense. Will he beat the odds or be a noble, mortal failure?

For two hours and 21 minutes the movie provides a pulse-quickening, rib-tickling showcase for Damon’s wonderfully fresh and resourceful acting, as well as a stirring tribute to Mark’s All-American virtues. But it’s not a one-man show. The Martian boasts the group and individual heroics that have energized our aviation classics from Howard Hawks’s Only Angels Have Wings to Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff. As soon as satellite images of the landing site on Mars suggest that Mark is still alive, NASA’s scientists, techies, astronauts, and bureaucrats work through their differences and pool their talents to try to bring him home. By the end, people as different as Rich Purnell (Donald Glover), an uber-geeky expert in astrodynamics with no sense of protocol, and Melissa Lewis (Jessica Chastain), Mark’s authoritative mission commander, prove to be lifesavers.

In this classic survival movie setup, Mark must concoct strategies for enduring Mars’s unforgiving temperatures and landscapes with supplies intended for a mission lasting little more than a month. What’s original and enlightening about the movie is that Mark not only tests his own practical intelligence but also the sturdiness and cleverness of NASA’s equipment and planning. One example: Mark is able to reconnect with Earth by locating and digging up the Pathfinder spacecraft and its Sojourner rover, which last transmitted data in 1997. (He bets that all he needs to do is dust off the vehicles’ solar-energy cells.) The results carry the comic charge of that sublime moment in Woody Allen’s Sleeper when he finds a 200-year-old VW bug in a cave and it starts right up.

This film’s matter-of-factness is its primary source of strength and humor. It’s the opposite of the campy yet compelling 1964 cult film Robinson Crusoe on Mars. Mark doesn’t have a NASA monkey in his own cute little spacesuit to offer survival clues and amusing chatter and pratfalls. He faces no alien master race descending from space to strip-mine Mars, and he meets no alien runaway slave who becomes his Man Friday and provides immediate human companionship.

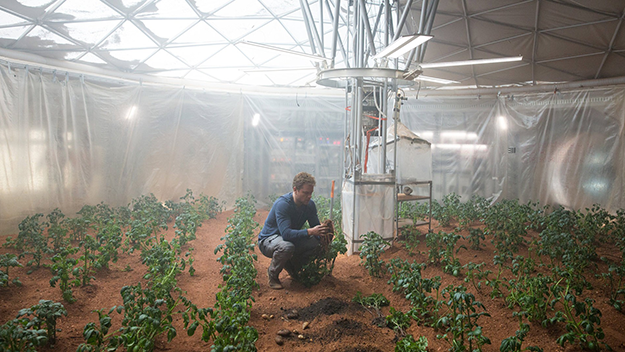

Instead, closely following Andy Weir’s novel (an Internet serial sensation that became a Kindle and print bestseller), Drew Goddard’s script concentrates on the hero’s never-say-die spirit and inexhaustible ingenuity. In one of many gimmicks that feel magically right, Mark narrates his adventure for a video log that he assumes will be his legacy. What’s touching and funny is that his entries chronicle his genius at endurance while expressing his droll upbeat personality. Telling the video camera that he must plant crops on a planet where they’ve never grown before, he vows: “Mars will come to fear my botany powers.”

He’s neither a pilot nor a military man, but, armed only with his degree from the University of Chicago, he follows the game plan Tom Wolfe repeatedly laid out in The Right Stuff: “In the skids, the tumbles, the spins, there was, truly, as Saint-Exupery had said, only one thing you could let yourself think about: What do I do next?”

The difference between Mark and the test pilots and astronauts in The Right Stuff is that ego and competition stoke their achievement. Mark is so modest that his bragging becomes a rich source of farce. His breakthrough triumph is using real potatoes set aside for Thanksgiving dinner to start a thriving potato patch, after turning Mars’s red dust into fertile soil by mingling it with his excrement. When his crop comes in, he declares that harvesting his plants means that he’s colonized Mars. “In your face, Neil Armstrong,” he proclaims.

Damon’s mastery of tone is as remarkable as his ability to calibrate Mark’s urgency; he’s never in the audience’s face. He delivers punch lines with an unforced irony, as if Mark is conjuring his own comic relief. He and the actors in the space crew—Chastain, Kate Mara, Michael Pena, Sebastian Stan, and Aksel Hennie—communicate their loyalty immediately. During a good part of the movie’s mid-section, NASA keeps the Hermes crew ignorant about Mark’s survival. The agency doesn’t want to burden them with guilt when they should focus on their return flight. Once they learn about Mark’s plight, Commander Lewis and her team prove that when it comes to saving a comrade, their daring has no bounds. Their audacity triggers a set of daredevil space maneuvers that culminates in a heart-stopping climax.

Maybe it takes a British director like Scott to see a signature American institution like NASA in all its struggles and glory. The movie is knowing about the agency’s political and PR challenges and admiring of the staff that faces up to them and keeps the space data flowing day and night. Scott has cast every part wittily, including the astronauts and the officers and personnel at the Johnson Space Center and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. Chiwetel Ejiofor, as Vincent Kapoor, the director of Mars missions, and Jeff Daniels as his boss, Teddy Sanders, the director of NASA, are perfectly matched infighters; they’re equals in subtlety and force. Kristen Wiig’s uniquely ambiguous looks—you often can’t tell whether she’s aghast or dumbstruck or coolly weighing possibilities—enable her to be alternately hilarious and commanding as Annie Montrose, NASA’s director of media relations. Sean Bean uses his melancholy air and weathered looks to smashing effect as flight director Mitch Henderson, whose only allegiance is to the astronauts. Mackenzie Davis as Mindy Park, the young satellite expert who becomes NASA’s first set of eyes on Mark, and Benedict Wong as JPL director Bruce Ng, contribute their own oscillating notes as they swing between exhaustion and elation.

As for the actors playing the Hermes crew, Chastain and Kate Mara (who plays computer expert Beth Johanssen) for the first time hold the screen like movie stars. Chastain burns off the tentativeness that marred her acting in Zero Dark Thirty. She moves with the physical authority of a born woman of action, while the petite Mara has the ability to tune a big audience into furtive shifts of emotion. Michael Pena as the pilot, Rick Martinez, combines intensity and relaxation to epitomize grace under pressure.

So does Ridley Scott. This virtuoso shooter has rarely made a movie that’s more varied in its images. He achieves a taut equilibrium while cutting among Mark’s grainy video, GoPro-style shots of minor cataclysms, stark, gorgeous slabs of Mars’s Spartan atmosphere, and crackling workplace footage of NASA and JPL personnel in crowded labs, offices, and control rooms. His narrative sense is stronger than ever. No subplot goes astray, not even when the action detours to China. He uses Commander Lewis’s disco collection—one of Mark’s few sources of escape—for comic counterpoint, but resists overusing it, which would have turned the film into a jokey cousin of Guardians of the Galaxy.

This director’s king-sized visual talent has often led him to take on sprawling heroic subjects, and in one case, Gladiator (00), he reaped popular success and awards. But I think his key films are The Duellists (77), which used its flabbergasting recreation of 19th-century nature paintings to frame the mystery of a never-ending grudge between two Hussars in the Napoleonic era, and Black Hawk Down (01), which subsumed his virtuosity into an immersive recreation of the Battle of Mogadishu.

In The Martian he’s made what may be his most personal movie by sticking to a just-the-facts approach. Watching this film you sense the kinship between Scott’s best big-studio epics, with their intricate craftsmanship and uncompromising instinct, and NASA’s boldest space missions, with their complex logistics and seat-of-the-pants inspirations. The Martian is a shot in the arm for the space program. It’s also a revitalizing celebration of Hollywood professionalism.