Deep Focus: Spider-Man: Homecoming

In Spider-Man: Homecoming, Spider-Man is an over-eager 15-year-old obsessed with earning full-fledged membership in The Avengers. His impatience at joining these costumed superstars and becoming a publicly acknowledged world-class superhero cements the character’s position in the Marvel Universe. But it also undercuts his appeal. When did Spider-Man, Marvel’s original crazy, mixed-up teenager, turn into such a go-getter, such a joiner? It takes the entire duration of the movie for him to make peace with his true self as “your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man.” The director, Jon Watts, who shares script credit with five other writers, tries to answer the demands of Marvel’s burgeoning movie empire while maneuvering Spider-Man back to where he belongs. The chorus of advance raves has declared that he’s hit the sweet spot. I’d call it sweet-and-sour.

As creator Stan Lee says in his 2002 autobiography Excelsior!, the idea behind Spider-Man was that “except for his super-power, he’d be the quintessential hard-luck kid. He’d have allergy attacks when fighting the villains, he’d be plagued by ingrown toenails, acne, hay fever, and anything else that I could dream up.” Homecoming has won a lot of goodwill with the simple act of returning its boy-hero (Tom Holland) to the middle of high school. But his teen alienation isn’t fab—it’s prefab.

We’re supposed to identify with Spider-Man/Peter Parker’s yearning for the smart, sweet, pretty upperclassman Liz (Laura Harrier), though his focus is almost always elsewhere. (It’s clear from early on that if he’d just slow down he’d get the girl.) He tells her and everyone else, Aunt May (Marisa Tomei) included, that he’s dashing off without warning or hunkering down behind closed doors because of a demanding internship with Stark Industries. What he actually does is ditch his backpack in back alleys and don the souped-up spider suit that Tony Stark/Iron Man gave him in Captain America: Civil War (2015). He logs as many after-school crime-fighting hours as he can in hope of impressing Stark himself and Stark’s chauffeur and right-hand man, Happy Hogan (Jon Favreau). He generates a good-natured frenzy that catalyzes both amiable slapstick and random destruction, which just about sums up the movie.

The latest reboot of the Spider-Man saga is programmed to be ultra-frisky, like a robot Jack Russell Terrier. The whole movie takes its cue from Tom Holland’s super-motivated Parker. The comedy-drama is geared to make Parker ease up. But the message has a hollow ring to it because the film is every bit as psyched on its own hyperactivity and gimmickry as Parker. It’s as if “Spidey” has become a synonym for “antsy.”

Holland provided a late-inning energy shot to Captain America Civil War: his youthful gusto was infectious, especially when he pulled off a giddy homage to The Empire Strikes Back. In Homecoming he’s inexhaustible, and exhausting. The movie wrings some genuine belly laughs from the way he experiences minutes as hours or shoots webs before he leaps. In a sequence that begins and ends at a suburban party, he aims his web-shooters upward, then realizes that there are no tall buildings to swing from in the suburbs. But the sequence generally lacks the wit and precision that would make it zing. It’s fun to see Spider-Man bang against curbsides, but most of the time he’s simply his own fall guy.

Marvel zealots may be too happy charting the expanding Marvel Universe to complain. Writer-director Watts links the action not just to Civil War but also to the Battle of New York at the end of The Avengers (2012), which left scraps of alien technology strewn around Manhattan. Homecoming begins when the owner of a small salvage operation, Adrian Toomes (Michael Keaton), goes to work clearing away the rubble. The newly formed Department of Damage Control shuts him down so white-collar “experts” can take over, despite Toomes’s protests over the havoc this cancellation wreaks on his crew and their families. As it turns out, the Damage Control agency is a public-private partnership between the U.S. government and Stark Industries. To a blue-collar entrepreneur like Toomes, it looks as if “the jerks like Stark who made this mess get paid to clean it up.”

The juiciest part of the movie is Watts and Keaton’s depiction of Toomes as a stand-up proletarian who detests elitism and crony capitalism. (Along with his work in Spotlight and The Founder, this makes for a string of classic Keaton characters.) Deciding to hang onto some alien tech left under a tarp on one of his trucks, Toomes deploys his workshop wizard (Michael Chernus) to invent a new generation of space-age personal weaponry, then turns his employees into small-arms dealers. Watts braids the two storylines together when Spidey stops three thugs in Avenger masks from robbing an ATM. They’re using gizmos emitting purple beams potent enough to destroy the superhero’s favorite bodega across the street. Spidey follow the lavender glow—and it ultimately leads him to Toomes.

Meanwhile, in Queens, Tomei waits for the script to give Aunt May something to do. She’s funniest when she walks in on Peter while he’s in his room with his excitable junior-league Sancho Panza, Ned (the ebullient Jacob Batalon), the only non-Avenger who learns his secret. Seeing Peter half-changed into civilian gear, she cocks an eye at him and half-asks, half-declares, “Maybe you want to put some clothes on, Peter?” The tang is all in the delivery; she puts an edge on pale-vanilla dialogue.

Meanwhile, at the Midtown School of Science and Technology, a slew of talented young performers try to brew up a hormone-driven, angst-filled atmosphere in an academy full of overachievers. I thought the outsiders in The Breakfast Club, the movie now considered the benchmark of high-school cinema, were simply third-generation stereotypes. In Homecoming, the student body is more diverse and the lunchroom is still divided between in- and out-crowds, but this pack is so chipper and sitcom-friendly it seems ready for The Brunch Club. Even the comic-book bully Flash (Tony Revolori) is a member of the Academic Decathlon team.

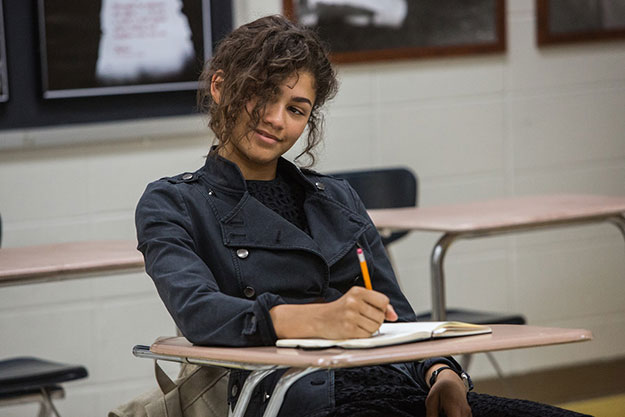

Watts stuffs Midtown High with clever touches. I particularly liked the pseudo-professional school-news reports, co-hosted by Angourie Rice’s semi-poised Betty Brant, which pop up on flat-screen monitors throughout the building. But the only teens who develop an authentic rapport with Pete are Ned, who’s overjoyed to be the kind of superhero’s sidekick known as “the guy in the chair,” and Disney Channel star Zendaya as the misanthropic, totally awake Michelle (an M.J. in the making), who’s excited about traveling to the Academic Decathlon championship in Washington so she can get in on some protest action at the various embassies.

Peter’s most intimate female relationship is with the Siri- or Alexa-like voice of his super-suit he dubs Karen. It’s actually the voice of Jennifer Connelly, who makes it somehow amusing to ask, “Should I engage Enhanced Combat Mode?”

Robert Downey Jr. pops in every now and then as Stark or Iron Man, and so does Chris Evans’s Captain America, via some uproarious motivational/educational videos. At times the film feels like Around the Marvel World in 133 Minutes. Gifted comic performers like Hannibal Buress and Donald Glover take small roles and get their laughs, though without leaving much of a lasting impression. The whole movie is like an overstuffed grab bag. Even the brightest ideas, like starting Peter’s saga with the cell-phone movie he made of the Avenger’s civil war battle, have snap and crackle but no emotional pop. And even the epic setpieces are devoid of awe and wonder and lyricism. They’re like comic-book splash panels without their disreputable charge or unruly graphic life.

I enjoyed Watts’s previous feature, Cop Car (2015). I thought he displayed a more striking and versatile talent than other low-budget filmmakers recruited for blockbuster franchises, such as Gareth Edwards (Godzilla) and Colin Trevorrow (Jurassic World). That film had sardonic undertones and a touch of poetry in its view of the Colorado landscape. But it was so thin it could barely sustain its 86-minute running time. What I found remarkable was that this youthful (now 36-year-old) director was more skillful with his grizzled villain—Kevin Bacon as a scary corrupt sheriff—than he was with his kid heroes. And the same goes with Toomes in Homecoming.

It’s not unusual for Keaton to be the saving grace of a movie. Still, his confidence and charisma as Toomes are extraordinary. As a performer, he’s burned away the pop-eyed, hyperbolic reactions and speed-freak line readings that gave verve to his early roles. As Toomes he sublimates Keaton specialties like semi-sneering glee into complex attitudes of bitter defiance and resolution. He’s not merely believable as a shrewd, aggrieved blue-collar entrepreneur, he also brings richness and weight to a man who belongs in a basket of deplorables. Midway through, he soars into action as a supervillain who’s like a dark carrion bird, with rotors unfolding near the edges of his wings. This garish alter ego feels both surprising and inevitable.

Keaton kicked off his most recent comeback appearing as a Hollywood actor who burned out playing a superhero named Birdman. In Homecoming he caps it as the Vulture.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.