Deep Focus: Southpaw

Jake Gyllenhaal is a gutsy, sophisticated performer, but his boxer hero in Southpaw fights like a crude Method actor. Named Billy Hope—presumably because he uses his fists like billy clubs and stands for hope and redemption—he can’t get his head into a match unless his opponent enrages him. With the light-heavyweight title on the line, he lets his opponent beat his face bloody before he launches an attack. On paper, it might read like an attention-grabbing tactic for a movie, but it’s rendered so melodramatically that it beggars belief from the outset. When Billy’s smart, ardent wife Maureen (Rachel McAdams) warns him that he’ll be “punch-drunk in two years,” she seems off by at least 18 months.

HBO’s Jim Lampley, who plays ringside commentator for the movie’s boxing scenes, has said in a promo interview that Hope is meant to be like Jack Dempsey, Joe Frazier, and Mike Tyson—champs who reigned with “short bursts of white-hot flame.” Lampley’s partner at ringside, Roy Jones Jr. (a remarkable champion himself), calls Hope “a brawler,” the kind of pugilist who gets knocked down, then pulls himself back up and KOs the other guy. Dempsey, Frazier, and Tyson were fighters who knew poverty and desperation and could vent their rage in the ring. Hope, a product of New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, grew up an orphan in the city’s childcare system, just like Maureen, who’s been with him since their tweens.

But in Southpaw we don’t really see Hope channel his fury from his hardscrabble past. We see him taunt rivals into pummeling him so he can tap into that wrath. Remember what Laurence Olivier told Dustin Hoffman on the set of Marathon Man? After Hoffman indicated that he’d stayed up for two nights partying before playing a scene in which he had to be exhausted, Olivier responded: “Well, why don’t you try acting next time?” In Southpaw, you keep waiting for his manager, Jordan Mains (50 Cent), to ask Billy Hope: “Why don’t you try boxing next time?” By the time Billy starts training with wily, idealistic Tick Wills (Forest Whitaker), who does ask him that question, the movie has slid into bathos.

Southpaw is a maudlin depiction of an arrested-adolescent celebrity lurching toward maturity and salvation. Hope’s boxing career doesn’t resonate the way Dempsey’s, Frazier’s, or Tyson’s did. The major social comment is a newspaper headline that calls him “The Great White Dope.” And despite speeches about Hope’s graduation from the School of Hard Knocks, he doesn’t function as a bristling working-class hero or antihero, like the fictional protagonists of Golden Boy, Body and Soul, The Set-Up, and Champion. Instead, Hope is a fantasy figure as retro and escapist as Little Orphan Annie. And the film is as gritty/glitzy as reality TV. Billy and his entourage belong to some virtuous brotherhood of Hell’s Kitchen street urchins. He and Maureen and their 10-year-old daughter Leila (Oona Laurence) live a suburban lifestyle that rivals Bravo’s Real Housewives, but without tainting their core purity.

Billy comes off as a melodramatic triple threat: a fervent husband, a devoted father, and a bit of a child himself. He relies on his wife to keep his home centered and himself sane. In the opening sections, McAdams and Gyllenhaal play off each other splendidly. When McAdams’s Maureen walks into an arena or a locker room, she owns the space as much as Billy. Clad in gladiator sandals, a curve-embracing grey and black dress, and golden links of jewelry that she sports like chains of office, she uses her looks to please and to rivet Billy. It’s easy to believe he responds instantly when she signals for him to get cracking.

Southpaw’s few scraps of emotional authenticity—even its moments of kitsch excitement—come primarily from these two valiant performers (and later from Forest Whitaker). Gyllenhaal turns himself into a fighting machine without losing his sensitivity. He gives Billy the hooded gaze and halting speech of a privacy freak who must do his job in public. Gyllenhaal’s physical transformation is impressive, but his spiritual metamorphosis is astonishing. It’s blissful to see Billy’s eyes clear when he’s alone with Maureen.

McAdams should get credit for summoning this gaze. She puts across the earthy practicality and passion of a wife who cares for her man body and soul, and she does it with candid humor and subtlety. When they’re in bed after the opening fight, and Billy jokes that he has two rounds still left in him, her charmed, amused response is what makes the moment magical. In front of flashing lights, McAdams is self-aware without being self-conscious. She’s more at ease than Billy at being on display. She exults in her wifely role, without limits. She informs 50 Cent’s swaggering Jordan, a manager who comes on as a buddy, that she’s the one who has Billy’s best interests at heart. When Maureen’s confidence flags, she wears a worried smile. It’s as if she knows that her ecstatic chemistry with her husband might be masking some dysfunction. Maureen is the brains, heart, and conscience of the whole Billy Hope operation. When, early in the film, he loses her to a stray bullet during a brawl between him and challenger Miguel Escobar (Miguel Gomez) and their respective squads of homeboys, his galaxy crumbles.

In his grief, Billy doesn’t just wallow in self-pity and revenge fantasies. He briefly pursues eye-for-an-eye street justice, but the only thing he hits is the bottle. The director of Southpaw, Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, The Equalizer), and his screenwriter, Kurt Sutter (a veteran of TV series like The Shield and Sons of Anarchy), turn Billy’s downward spiral into a bummer of a rollercoaster. He starts hemorrhaging money to cover rocketing legal fees and a ruinous overhead. He lets Jordan prod him into protecting his title before he’s ready for it. (The manager’s motto: “If it makes money, it makes sense.”) Without Maureen psyching him up and urging him on, Billy can’t function in or out of the ring. During his return bout, no one triggers Billy’s anger and his reflexes except the referee who ends the fight. (Billy head-butts him.) Fuqua cut his teeth on music videos and has rarely worked in television. But the sensibility behind films like The Equalizer and Southpaw is TV soap opera and pulp carried to extremes. Billy loses his mansion to the bank, his daughter to child services, and his manager and trainer to his bitterest enemy. He becomes an overgrown lost boy.

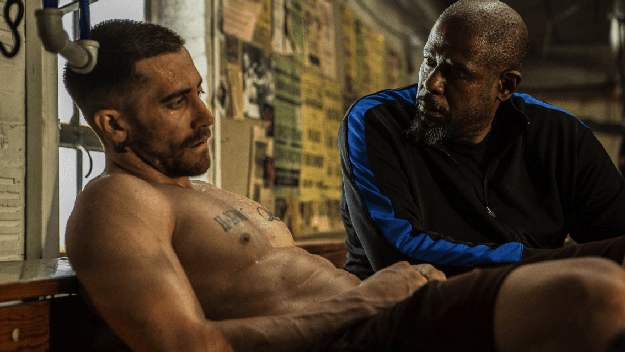

It’s a grim picture, to be sure. But true to soap-opera conventions, Fuqua and Sutter keep flashing signals that Billy will set everything right. He maintains a genuine brotherly rapport with his old crewmember Jon Jon (Beau Knapp), who tells him he was never in business with Billy for the money. Desperate to regain custody of Leila, Billy swallows his pride to work as a night janitor at Tick Wills’s gym, then trains according to Tick’s rules, which demand respectful behavior and defense and fluidity in the ring—“punching for points, not blood.” You can tell he’s matured when he worries about Tick’s most at-risk teenage pupil, a lovable doomed soul called Hoppy (Skylan Brooks).

Whitaker’s dry delivery and his dynamic sort of gravity bring some zing to this film’s soggy mid-section. If Tick’s rehabilitation of Billy sticks with you, it’s because Whitaker, too, elevates everyone around him. Few actors rival his ability to summon genuine reactions from a co-star with an unexpected pause or an unconventional beat. It’s both exciting and emotionally satisfying to see Tick section off the ring with long red workout bands and force Billy to bob and duck as if he’s doing a limbo rock. It becomes a visceral expression of Tick raising Billy’s game. The movie peaks when Tick signs up Billy for a charity exhibition match. You can’t help pulling for Billy to control his temper and display his expertise—and, you know, to box. By contrast, the final bout between Billy and Miguel Escobar, the irritating showboat responsible for his wife’s death, is anticlimactic and unbearably manipulative. Not only does Billy get to bring his daughter to Vegas for the fight, but he also manages to see that she’s accompanied by her smart, pretty caseworker. Naomie Harris, so witty in Skyfall and so touching in the National Theatre’s Frankenstein, imbues her with just the right degree of tough love—well, really just tough sympathy. But her role is so underwritten that she can’t begin to fill the dramatic vacuum left by Maureen’s death.

Like the Rocky sequels, Southpaw generates rooting interest by turning a successful fighter into an underdog. Fuqua, a recreational boxer as well as a fight fan, has geared both the drama and the filmmaking to connecting with the mass audience. He exploits the oomph of boxing caught in close-up. As he explained to The New York Times, he uses the vocabulary of televised fights and sports journalism—master shots of the ring and angled views from the perspective of judges and fans—then moves into extreme close shots, including punches shown from the point of view of the glove. Fuqua aims to deliver the thrills TV audiences expect without minimizing the sport’s brutality. But there’s nothing imaginative or fresh about this style. Lampley and Jones’s running commentary and Fuqua’s on-the-nose shooting and editing leave few evocative images or signs of athletic personality for viewers to discover for themselves. In films by directors as different as Robert Wise, John Huston, Jim Sheridan, and Ron Shelton, simpler is better. You can’t think about the boxing in their movies without summoning nuanced, even tactile memories of their actors. Robert Ryan turns himself into a vehement, rangy figure out of a Thomas Hart Benton painting in Wise’s The Set-Up. Stacy Keach fights physical and emotional gravity to stay on his feet in Huston’s Fat City. Daniel Day-Lewis boxes as resolutely as if the fate of Northern Ireland depended on it in Sheridan’s The Boxer. Antonio Banderas and Woody Harrelson turn from comical best friends into shockingly fierce battlers in Shelton’s Play It to the Bone. In Southpaw, the key match carries no surprise or hint of revelation. It’s not a crucible for Billy, but a certification of his moral improvement. Despite Gyllenhaal’s best efforts, you don’t believe in a man called Hope.

Rapper Marshall Mathers, aka Eminem, who executive-produced the sound track and contributed two songs, catalyzed this movie when he asked Sutter to pen a new version of King Vidor’s The Champ, the weepie about a former heavyweight battling for custody of his son that King Vidor made in 1931 with Wallace Beery and Jackie Cooper; Franco Zeffirelli remade it in 1979, with Jon Voight and Ricky Schroder. Sutter protested that he didn’t want to do another remake. Instead, he vowed to draw on Eminem’s life for inspiration. He centered it on a southpaw fighter because lefties “are to boxing what a white rapper is to hip hop; dangerous, unwanted, and completely unorthodox.” It was an admirable ambition, but the way it’s come out, Southpaw seems to have been made for righties.