Deep Focus: By Sidney Lumet

The filmmaker best known as the spirited chronicler of 20th-century New York’s vitality and decay, notably in Serpico (1973) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975), gets the Very Important Director treatment in Nancy Buirski’s By Sidney Lumet, a 109-minute rendering of a 14-hour-plus interview conducted over five days with Lumet in 2008 by the late documentarian Daniel Anker. It’s not a good look for him. Don’t get me wrong: Lumet was an important director, but for reasons that defy deification. Many directors revered him not because he had an unblemished record of accomplishment, but because he stayed in the game, putting out dozens of pictures with equal intensity whether or not the material warranted it. Jean-Claude Tramont, the gifted Belgian-born director whose career stalled after the Gene Hackman–Barbra Streisand comedy All Night Long (81), would occasionally sigh and tell me: “Sidney Lumet has the right idea. He never leaves the stage. His muscles don’t go slack. You may not like the movie he has out right now, but he’ll be back.”

In By Sidney Lumet, the director comes off as a shrewd, modest realist from the start, insisting that what excited him about his astonishing debut, 12 Angry Men (1956), was simply the chance to do a film, not to explore the American justice system. By and large Lumet takes the Fifth when interviewer Anker and producer-director Buirski try to pin him down as a moralist or a tragedian of family life. He resists getting characterized as a philosopher rather than a director-dramatist and ultimately agrees only to being obsessed with what is “fair.” Buirski anchors the movie with Lumet’s recollection of a traumatic wartime incident—witnessing a U.S. soldier sweep a 12-year-old girl off a platform and into a train compartment outside Calcutta, then gang-rape her with a group of GIs. His disgust and his self-loathing at not trying to stop it or express his outrage don’t resonate with the rest of the documentary. Buirski positions it as a haunting moral quandary, but it comes to seem more like an expression of personality for a man who was never an activist but managed to vent his political anger and radical attitudes in his moviemaking.

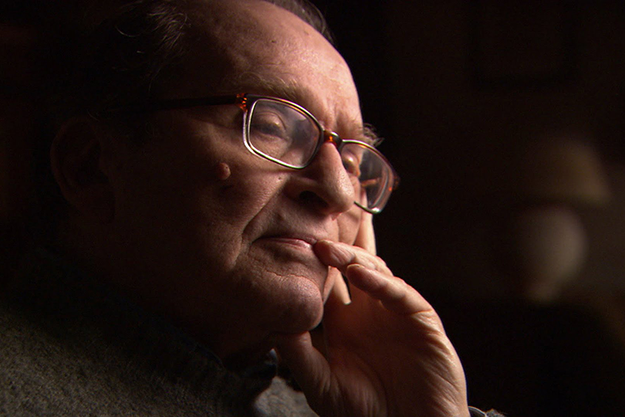

Lumet’s refusal to be thrust into a critical procrustean bed generates humor and tension for Buirski, and his shrewdness and animal vitality at age 83 (he died three years later) help keep the documentary alive. Of course nothing can stop Buirski from concentrating on her twin theses that Lumet is a political-radical artist and that his films comprise a harrowing dissection of family life. She tends to linger on leaden or grinding movies that support one or both of her theses—Prince of the City (1981), Daniel (1983), Running on Empty (1988) and Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007). Watching mediocre, overwrought, or interminable clips from films like these, and from his deserved flop turned cult film The Wiz (1978), and from some official classics, like The Verdict (1982), dulls the eclectic allure of Lumet’s achievement—as does using Lumet’s masterpieces simply to illustrate her reductive analysis.

When a director creates 44 films and scores of TV programs, it seems to me inevitable that movie-lovers (critics included), if they’re honest, view them in toto not as a giant, coherent tapestry but as a sprawling collage, with several standout sections and a collection of glittering prizes. Some of my favorite Lumet movies are generally forgotten, like The Hill (1964), his immersive descent into a British stockade in Libya during World War II (it does get adequately covered in By Sidney Lumet). Some never had any reputation at all, like The Deadly Affair (1967), one of the best of all John le Carré adaptations. I treasure lots of Lumet films simply for individual performances, like Lovin’ Molly (1974), his loose-jointed adaptation of Larry McMurtry’s Leaving Cheyenne, which boasts Blythe Danner at her most seductive and free-spirited, and his bumptious The Sea Gull (1968), with a lyrical James Mason and an incandescent Vanessa Redgrave, and his florid The Fugitive Kind (1962), based on Tennessee Williams’s Orpheus Descending, which features two of Marlon Brando’s soaring big-screen arias, though he and Anna Magnani misfire as co-stars.

For me by far the greatest Lumet movies, next to 12 Angry Men, are his masterly TV production of Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh (1960), and his nonpareil big-screen mounting of O’Neill’s greatest play, Long Day’s Journey Into Night (1962). But directors don’t always carve out a place in film history simply by creating a succession of masterpieces. Anyone who grew up as his films came out, and, especially, saw them in New York, experienced the energy and intensity of the bond he forged with the audience in crowd-pleasers like Serpico (in which Pacino gave a countercultural star performance) and even crowd-agitators like Dog Day Afternoon (in which Pacino, John Cazale, and Chris Sarandon gave transcendent performances). Watching Serpico not long ago on a huge video monitor with a director friend who is a master craftsman, we had to turn it off; the slipshod technique and bad-cop clichés suddenly seemed appalling. But in the theater it generated a galvanic atmosphere as the audience responded to Serpico’s put-on humor, like his riff on having a heroin-sniffing mouse, and his mordant street wisdom, including his rueful statement that cops “do not wash our own laundry—it just gets dirtier.” Lumet, whose own roots were in the theater, tells Anker that he rarely thought about how his movies would play in the cinema. Still, he grew up as a child stage actor and remained a theatrical creature down to his bones. His movies sometimes depended on audience reactions to complete them.

By Sidney Lumet doesn’t get at the ways, good and bad, that Lumet directed “for effect.” The movie seems to adopt the same technique as Jake Paltrow and Noah Baumbach’s scintillating De Palma, but Anker and Buirski don’t share the same easy rapport with their subject. Lumet ends up repeating, in more desultory fashion, anecdotes and insights that are packaged with more zip on, say, the 12 Angry Men Blu-ray.

The documentary is strong on Lumet’s youth and his relationship with his father, a stalwart of New York’s Jewish stage world, who read Hamlet to his son in Yiddish. (Lumet is charming when he accounts for his operatic excesses by saying he heard Madame Butterfly sung in Yiddish.) The documentary swiftly sketches in the egalitarian and communal social conscience of Depression-tested left-wing Jewish families of Eastern European descent and their sympathy for the Soviet Union. But the film is vague or confusing about the Cold War and the McCarthy era. Lumet goes on and on about the climate of fear, but all he has to say about the disclosure of Stalin’s crimes against humanity is that many people found them “deeply upsetting.” The documentary depicts the political turmoil of the 1960s and ’70s as if it were directly analogous to that of the 1930s. So much for the counterculture or the New Left.

In one of his final big-magazine interviews, Rolling Stone dubbed Lumet “The King of New York,” but in this documentary his insights about Gotham’s transformations are minimal. He basically says that growing up in New York accustomed him to confined spaces and that he could find locations and lighting to fit any theme or mood. All that may be true, but Lumet was renowned specifically for capturing the city’s volatility and high anxieties in the 1960s and ’70s. Once Elia Kazan began writing novels, Lumet became the New York director, and he inevitably portrayed it as a city on the verge of nervous collapse. He did so not just in landmark movies like The Pawnbroker (1964), but also in serviceable trash like The Anderson Tapes (1971). Partly because of his marrow-deep connection to Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, his movies often connected vitally to the Zeitgeist, no matter if they were stiff or over-praised. As Paddy Chayefsky rants go, I might prefer Arthur Hiller’s The Hospital (1971) to Lumet’s Network (1976)—The Hospital is funnier and less pretentious—but there’s no question Network had more impact. That’s why Lumet gets away with a rare grandiloquent moment when he says that in Network, the media really are a metaphor for America.

Lumet’s great successes are acts of inspiration—sometimes high, sometimes low. Take Lumet and Rod Steiger’s devastating portrait of a Holocaust survivor who revives himself via fresh pain in The Pawnbroker. As Steve Vineberg wrote in Method Actors: “Between its bull’s attack on the extremely volatile subject matter, and Steiger’s amazing acting, it scrapes you raw. And in some way, everything that’s wrong with it—its obviousness, Lumet’s close-in technique, the mid-sixties visual jazziness (to match the jazz score), the symbolism—works for it in terms of emotional force.” Pauline Kael, who wrote with terrific verve and insight about Lumet (notably in her long reported piece, “The Making of The Group”) liked to ascribe his success with O’Neill simply to the union of their intense, relentless temperaments. But his O’Neill productions are superbly felt-out and crafted, and there’s a touch of poetry to his handling of Long Day’s Journey Into Night. In that movie, as in 12 Angry Men, Lumet and his frequent cinematographer, Boris Kaufman, prove themselves utter masters of the close-up. Katharine Hepburn so totally inhabits the character of the drug-addicted mother and wife, in her fragility and whimsicality and grief, her life-torn sensitivity, that her most fleeting expressions of drug-induced euphoria and infantile play-acting illuminate her lines. In his terrific book, Making Movies, Lumet himself describes her performance—with its shivers of panic, and glassy-eyed resignation—as “the personification of tragic acting.”

One of the most revealing things Lumet says in By Sidney Lumet is that his moment of truth as a director usually comes when he decides what a film is about. For example, both Daniel and Running on Empty, he says, are about children paying for the passions of their parents. He confesses, though, that when he did Long Day’s Journey Into Night, he didn’t try to narrow his goals. As he wrote in Making Movies: “Four characters come together and leave no area of life unexplored.”

Watching By Sidney Lumet, we admire his antagonism to being pigeonholed while wondering whether, by tying movies too early to their themes, he ended up pigeonholing himself. He was such a dynamic, talented moviemaker that he often surmounted the limits of his own concepts. Watching The Deadly Affair, we can appreciate all the thought that went into Paul Dehn’s incisive script, but Lumet’s direction is what imbues the film with its poetic, electric poignancy. As le Carré’s signature character, George Smiley, here renamed Charles Dobbs, James Mason does a middle-aged variation on the odd men out he played for Carol Reed when he first became a star. As he strives to crack the mystery of a Foreign Service official’s suicide, Mason grounds the character’s disappointment and concealed strength in his weathered features and brushed-fur voice: everything about him says “bloodied but unbowed.” Lumet surrounds Mason with a cast of his peers, including Harriet Andersson as his adored, unfaithful wife, Simone Signoret as the official’s widow, and Harry Andrews as the retired inspector who becomes Dobbs’s right-hand man. The cinematographer, Freddie Young, works as beautifully with Lumet as Boris Kaufman did, giving the film an aptly brooding, almost decolorized look.

By Sidney Lumet is just solid and intriguing enough that when his list of credits unspools at the end, viewers fresh to his oeuvre will be marking titles to rent, buy, and stream. I mean to catch up to Stage Struck (1958), The Last of the Mobile Hot-Shots (1970), and The Offence (1973). Wouldn’t every movie-lover want to catch up on the director who created the peak production of what is probably America’s greatest play?

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.