Deep Focus: Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark

All images from Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (André Øvredal, 2019)

The books behind Guillermo del Toro’s new production, Alvin Schwartz’s compulsively readable Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark series, collect folkloric scraps and urban myths. They include bleak and often scary-funny campfire tales like “Harold,” about a scarecrow who comes to life; open-ended horror fragments like “The Big Toe,” about what happens after a boy plucks a big toe from the family garden—it’s rooted to something underneath the topsoil—and his mom cooks it, his father carves it, and they all eat it; and grotesque fantasies like “Me Tie Dough-Ty Walker,” about a bloody talking head that drops into a fireplace—the kind of story kids tell at sleepovers before pouncing on each other and screaming (as Schwartz suggests) “AAAAAAAAAAAAH!” Then there are mini-fables that provoke primal fears, like “The Red Spot,” in which a person unknowingly incubates spider eggs under her skin, and literal nightmares like “The Dream House,” about an artist who dreams that a pallid specter rouses her from sleep, in a room with nailed-shut windows, and murmurs, “This is an evil place. Flee while you can.”

The credits list del Toro as producer and co-writer of “the original story” (along with Patrick Melton and Marcus Dunstan), which might seem strange for a film directly based on Schwartz’s stories. But del Toro’s efforts are central to what he and Norwegian director André Øvredal and American screenwriters Dan and Kevin Hageman try to pull off here. To recreate, in cinematic terms, the visceral impact of Schwartz’s thrice-told tales, the filmmakers embed them in their own movie-mad youths. They fashion their version of ’80s Amblin films about kids facing outlandish perils, such as, at the low end, The Goonies, and, at the high end, Gremlins. They try to mirror Schwartz’s “OOOOOOOOOOOOH”s and “AAAAAAAAAAAAH”s with a secession of “Gotcha!” moments, and at least half the time, they succeed.

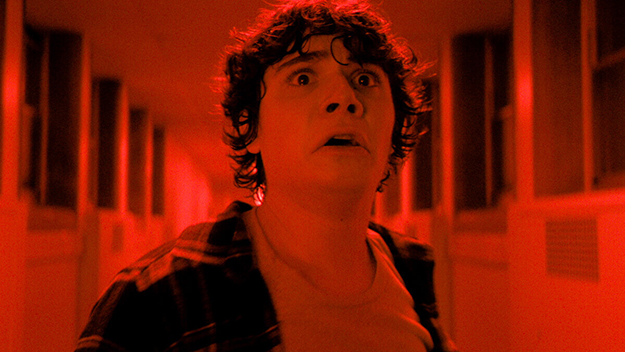

The moviemakers concoct a small-town high-school Halloween movie about geeks and freaks in mythical Mill Valley, Pennsylvania, in 1968. The misfit heroes’ supernatural travails begin after they provoke a bully from the in-crowd. Bespectacled Stella (Zoe Margaret Colletti), an aspiring horror writer, doesn’t feel like trick-or-treating, but her pals, Auggie (Gabriel Rush), a slender, cultured fellow, and Chuck (Austin Zajur), a squat, ribald clown, persuade her to hit the streets in order to exact excremental revenge on teen-macho Tommy (Austin Abrams), who has made an annual ritual of absconding with their treat bags. They humiliate the jerk, and when Tommy goes on the counter-offense, they pick up unlikely allies: Ramón (Michael Garza), a stranger just passing through town, and Ruth (Natalie Ganzhorn), Chuck’s fashion-conscious older sister.

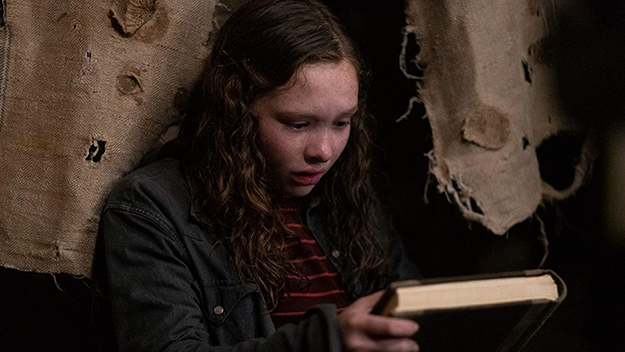

Their big mistake is stopping at the village’s haunted house, where, long ago, the family owners of the town’s founding industry, a paper mill, locked up their supposedly insane daughter Sarah (Kathleen Pollard) before stashing her in a mental hospital. Sarah reportedly lured young children to their deaths. So it’s not surprising that morbidly curious Stella would steal a copy of a dusty journal in which Sarah wrote supernatural stories in red ink. Or is it blood? We soon learn that Sarah’s spirit, now awakened, can pen new grotesqueries about contemporary subjects, like the demise of Stella’s pals and Tommy. These entries appear on a page before each comes face to face with fate. The ink is blood: fresh blood. The idea is that “you don’t read the book: the book reads you.”

All of this sounds like inordinately heavy machinery to support a wispy, episodic narrative. But cinematographer Roman Osin’s ruddy-brown autumnal tones, production designer David Brisbin’s evocation of an analog America during the week when Nixon and Agnew were elected, and Øvredal’s exuberant, straightforward direction, full of smash cuts and exaggerated sounds, often float this odd, misshapen boat. Del Toro and company take key visual cues from Stephen Gammell’s ghastly-beautiful illustrations for the books, then embellish them inventively. The scarecrow, Harold, looks remarkably like Gammell’s pug-nosed, cauliflower-eared, straggly-haired straw man, but here we can see bugs skitter in and out of its body, their shiny thoraxes and abdomens bringing its eyes creepily to life. The filmmakers mimic the huge doughy torso, bottomless chin, and thin, serrated mouth of the pale, bloated wraith in “The Dream,” then multiply the monster’s incarnations. Sometimes they fake-gild a wilted lily—as when they combine the grim talking head of “Me Tie Dough-ty Walker” with the reconnecting body parts of “What Did You Come For?” At other times, they flub the imagery but compensate with pure suspense—as in their precise, creepy variation on “The Big Toe,” which culminates in Auggie struggling to suss out what’s haunting his room as he peeks out from under his bed. And they get everything right when the “Red Spot” emerges on Ruth’s face as a giant boil just as she’s about to take the stage in the perfect choice for a 1968 school play: Bye Bye Birdie.

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark is hardly an actors’ movie. But Del Toro and Øvredal have assembled a gung-ho cast. They bring freshness and a welcome physicality to their types. Thanks to Rush, even high-toned Auggie, who dresses as “Pierrot” for Halloween, never comes off as pathetic and effete, even when his mom fusses over the crotch for his clown suit. And the narrative ingenuity rarely flags, building to a duel between dual realities in that haunted house.

So why did I begin to get increasingly restless as the film went on? Partly for the same reason I once did at some Amblin films. No matter how well acted, the mini-dramas meant to add human dimensions, like Stella’s sadness and guilt over her mother leaving her father, feel trumped-up or tacked-on: they’re artificial “heart.” And the movie’s cleverness at threading Schwartz’s stories together and integrating them into an original tall tale gradually eliminates several sources of their power: their off-the-cuff absurdity, the arbitrary, unspeakable excesses of their cruelties, and their jagged unpredictability. In this film, everything is explained and rounded out: each piece of sadism is designed to exploit a specific preoccupation of a certain character.

Still, a subplot about poisoned public waters, which also contains a plea to “believe the female victim” (even one that turns into a monster), creates a contemporary resonance. So do Ramón’s confrontations with racists—the sheriff (Gil Bellows) who profiles him as an outsider, the bully who paints “Wet” on his car’s hood and “Back” on its trunk. And the choice of 1968 conveys the unstressed point that in a climate of fear and paranoia, such as the Vietnam-Watergate era, people are apt to fall into confusion or complacency and act against their own best interests.

The movie uses the Nixon-Agnew election the same way Warren Beatty and Robert Towne did in Shampoo—as a barbed backdrop to personal calamity. The Beverly Hills hair stylist in Shampoo refers to his job as “doing heads.” This film is about losing and breaking them.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.