Deep Focus: Rock the Kasbah

For Barry Levinson’s nimble, big-hearted comedy-drama Rock the Kasbah, writer Mitch Glazer has come up with Bill Murray’s richest role in years, one that exploits the comedian’s love of tawdry old-time show biz and rejuvenates him at the same time. The result is a frisky, inventive, and endearing performance in a movie that is, like its lead character, full of surprises.

As Richie Lanz, a one-time rock tour manager who sees himself as an inspired agent/manager and signs up with his protégé for a USO tour to Afghanistan, Murray displays the ability to think on his feet and on his back and in all postures in-between. He has a touch of the demotic poet in him: he spins out juicy bits of rock history to lend a mythic size to the seediest situations. When his assistant, Ronnie (Zooey Deschanel), also his only pro or semi-pro client, refers to their bumpy plane ride into Kabul as a “death trip,” he says, no, the Bangles tour in ’85—that was a death trip.

The modest miracle of this movie is that, by the end, it’s both funny and touching to discover that Richie considers the contract between management and talent a sacred bond. By then, he’s discovered, signed, and imperiled a Pashtun village girl, Salima Khan (Leem Lubany), who becomes the first female contestant on the American Idol-like TV show, Afghan Star. The real series was chronicled in a moving 2009 documentary named after the show. Levinson and Glazer dedicate this feature to one of its trailblazing female competitors, Setara Hussainzada, who sang and danced in front of the camera, received death threats, then moved to Germany.

Salima lets down her niqab and sings, in English, Cat Stevens’s biggest hits from the early Seventies. Songs like “Wild World” and “Peace Train” would be perfect for this movie even if Stevens hadn’t converted to Islam in 1977 and changed his name to Yusuf Islam. Rock the Kasbah restores the truth to the honorable clichés of Show Biz Past, like “the show must go on” and “talent will out”—tenets often forgotten in pop arenas where bad behavior and burnouts are predictable. They become matters of life and death to Richie and Salima.

Refreshing in its unexpected mix of cynicism and hopefulness, Rock the Kasbah refuses to get moralistic about a character like the spangled hooker Merci (Kate Hudson), who hires herself out for decadent Kabul parties when she isn’t running her own one-woman bordello out of a trailer (a double wide). It respects her ambition to accumulate a large enough nest egg to underwrite a new life in Oahu.

The movie finds laughs in the bravado of two unhinged arms dealers, Nick (Danny McBride) and Jake (Scott Caan), who turn into adrenaline junkies while pushing their luck and abandoning all scruples, as well as in the unlikely partnership between Richie and a mercenary, “Bombay” Brian (Bruce Willis), who would have to be called “grizzled” if he had any hair. (Richie, in a piquant example of his logical banter, asks Bombay whether he should actually be nicknamed “Mumbai.”)

Rock the Kasbah gains emotional traction when it depicts the cross-cultural power of entertainment and the proverbial honor among thieves. Or mercenaries and whores, like Bombay, who becomes Richie’s brother in arms, and Merci, Richie’s partner in every way. The movie gracefully morphs from a lower-depths backstage dramedy to a stirring humanistic fable, without becoming hokey—a tribute to Levinson’s characteristic wit and mastery of tone and to Murray’s breadth as a performer.

At the start, Richie comes off as a sly, low-key dissembler: a minimalist Music Man exploiting a potential client’s illusion of talent. Working with Ronnie out of two Van Nuys motel rooms, he sinks into a subterranean dimension of boredom and disgust as he listens to a rock diva wannabe named Maureen (Sarah Baker) murder some lyrics while auditioning for him. Nevertheless, he convinces “Mighty Mo” that she could become as successfully “irritating” or “annoying” as Celine Dion, Nicki Minaj, and “sometimes” Christina Aguilera. She gladly writes him a check for $1,200.

Murray turns that scene into a brilliant comic aria, using unpredictable timing and phrasing to keep both the audience and Mo off-balance. You think you know where he’s headed when he starts checking off her failings, but even when he talks about a grain of sand entering an oyster shell and producing a pearl, you don’t expect him to end up invoking Dion, Minaj, and Aguilera. Murray begins his spiel slowly and never goes into overdrive; his confident, rhythmic line of gab lassoes his client’s psyche. In just one scene, Murray conjures electric variations on the spacey miasma he generates when playing melancholy characters in slice-of-life art movies (Broken Flowers), and the freewheeling put-on artistry he employs to perk up his scenes in Wes Anderson’s facetious epics.

When Richie accompanies Ronnie to a gig in a Valley grill, there’s nothing tuned-out or put-on about him. He’s with her all the way. From the back of the room and in front of the bar, he stage-directs every extroverted gesture she should be making instinctively as she covers the Meredith Brooks smash “Bitch.” (Deschanel is also aces, letting us know with a ticklish hesitancy that Ronnie can sing, but probably should belt out her own songs.) When Richie tries to stoke enthusiasm in the dwindling audience, her biggest fan turns out to be a USO representative. He sells Richie on touring Ronnie through Afghanistan. In an antic-poignant farewell scene, Richie sneaks a goodbye to his precocious little girl Dree (Avery Phillips) through a corner window in her house before his divorced wife calls Dree away to watch Ann Coulter perform on Dancing with the Stars.

Even a role as small as Richie’s ex-wife is played by an actor as great as Kelly Lynch (Drugstore Cowboy). While getting the best out of Bill Murray, Levinson directs a star vehicle as if it weren’t one. Characters who in other hands might simply fulfill a plot function, such as Ronnie, emerge as attention-grabbing individuals. Deschanel sparkles even when Ronnie is stoned and smudged with drooping makeup. She may just be a zircon in the rough, but she’s smart and put-together and she has chops. If she can believe in Richie’s self-created legend, almost anyone can. She’s fragile enough to need his support but she’s also sensible. The incendiary sights between the Kabul Airport and the (not-so-) Majestic Hotel are enough to make her flash an SOS about the USO.

In Afghanistan, Levinson’s unblinking yet restrained compassion and humor-suffused sanity create a black-comic reality that delivers a shock or a laugh at each hairpin turn or hazardous intersection. Everyday dangers are present at any second: an IED or a suicide bomber could explode, the Taliban could mount an incursion, or independent warlords could wreak havoc by taking over city blocks or overturning desert rivals. And this risky environment breeds extreme escapes. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (in a painting) set the tone at the hotel bar and cafe. When nihilists like Nick and Jake want to blow off steam, they head to the Vulcan club, a decadent hot spot that’s like a postmodern speakeasy. As Lawrence of Arabia would put it, after all that, the desert is appealing because it’s clean.

Collaborating with an agile and eloquent cinematographer, Sean Bobbitt (12 Years a Slave), Levinson creates a novel, ruthless atmosphere without getting bogged down like the U.S. military. Levinson and Bobbitt don’t overdose on carnage—they convey the buoyant persistence of life, whether in the capering children of Kabul or the pent-up longings of traditional rural villagers. Levinson keeps the movie lithe as he traces elusive bonds that will lead Salima on and off and on Afghan Star and Richie and Bombay Brian into a showdown with bad guys in the desert.

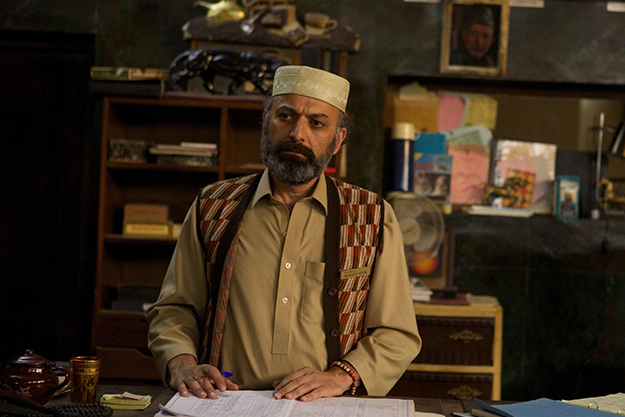

The good guys include Salima’s sober, conservative father Tariq (Fahim Fazli), the chief of a righteous Pashtun village several hours from Kabul. Richie discovers Salima after delivering a shipment of ammo from Nick and Jake to Tariq. She’s covertly intrigued when Richie seals a deal by strumming and belting out Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the Water.” Lubany’s passionate presence helps bring an easy, unselfconscious lyricism to images of Salima sneaking looks at Afghan Star and singing in a cave beyond the village. Later, her heightened feelings seem to spread across the country when friendship groups and families huddle together in the dark to watch her compete.

As the narrative weaves together heroism, anti-heroism, and casual villainies, Levinson builds his movie the way Richie builds his business—on the power of relationships. Hudson gives Merci a tough, stubborn intelligence that Richie will rely on, and Arian Moayed transforms the stock character of a native taxi-driver, Riza, into Richie’s delicate conscience. You’re glad to see minor recurring characters, like Taylor Kinney’s Private Brian, who is valiantly matter-of-fact in the face of constant crises. Throughout, there’s method to Richie’s madness, particularly when he wins Bombay’s allegiance by manipulating his ambition to write a mercenary memoir. Willis is both understated and out-there as Bombay, a hard-bitten character who ultimately tunes into Richie’s bizarre wavelength.

The intricate plot pays off because of Murray’s protean performance. The action escalates to a Middle Eastern version of a Western confrontation—a “Save the Alamo” climax complete with Dylan wailing “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” (from Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid) on the soundtrack. Few contemporary actors could be as wised-up, hysterical, and soulful, simultaneously, as Murray is when Richie communes with Lubany’s ardent, spiritual Salima.

To borrow from John Sebastian, at that moment you believe in the magic in a young girl’s heart. In Rock the Kasbah, music “can make you feel happy like an old-time movie” and even “free your soul.”