Deep Focus: The Puppet Master: The Complete Jiri Trnka

Bayaya

Jiri Trnka didn’t craft his puppet-cartoon shorts and features merely to imitate life. His endlessly original and inventive movies incorporate life, or transcend it. Trnka insisted that he was “local,” and drew many of his subjects from Czech folk culture. But his sophistication energized his work, even as his warmth and freshness gave it emotional appeal. Best of all, he had “vision” in the primal sense—a new way of seeing.

The whorls of nature and the wrinkles of human experience come together in his flexible, robust style. He renders peasant environments with forceful elegance and aristocratic life with a crackling satirical precision that suggests unruly depths. He creates his own high-low universe, from classical Cocteau dreamscapes to Bruegel-esque country saloons. In this alternate reality, stubby children with round heads and button noses hug the ground. Strong women with sly or doleful eyes glide on willowy legs through the deep forest. Lopsided fellows stumble along streets and alleys, their razor-edged noses knifing the air.

Trnka invests all these figures—farcical, tragic, or heroic—with a peculiar charisma and gravity. After carving or molding his puppets and designing or painting their expressions, he rarely animated their eyes or features. To do so, he said, would disrespect their identities as puppets. What’s astonishing is that, without raising an eyebrow or moving their lips, they convey multitudes. Their feelings change from scene to scene, according to how they’re angled toward the camera or how their profiles take the light. The extra split-second it takes for us to link narration, lyrics and dialogue to each character heightens our attention.

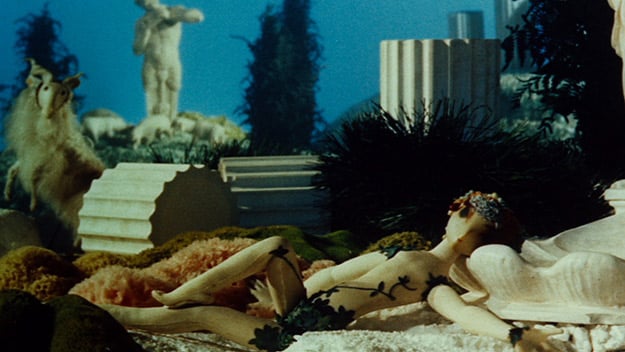

A Midsummer’s Night Dream

Trnka’s belief in his figurines’ integrity endows his movies with dense yet scintillating textures. They help him sustain the fierce whimsy of his one-of-a-kind homage to peasant endurance, The Czech Year (1947); the surging potency of his Bohemian mythic history, Old Czech Legends (1953); the intricate fantasy atmospheres of Bayaya (1950), The Emperor’s Nightingale (1948), and A Midsummer’s Night Dream (1959); and the lived-in black comedy of his anti-military farce, The Good Soldier Svejk (1954).

The Czech Year starts with the toot and bang of a plucky country band—Trnka announces his arrival as a major artist with the sounds of pipe and drums. The idea of an episodic pastorale based on seasons and holidays sounds like sappy kitsch. It must have roused the skepticism of European audiences who’d seen their countries ravaged in the recent war, and of outsiders who wondered what all these lovable peasants were doing when Jews and gypsies were carted off to concentration camps.

But Trnka’s exuberant spirit blows away doubts and objections. His movie attempts to preserve a rambunctious, communal way of life that no longer is and possibly never was. The director’s upfront artifice registers with a stunning immediacy that wipes out any sickly nostalgia. His squat characters could be children play-acting, especially because a youth chorus or boys’ choir does the nonstop singing on the soundtrack. This unusual ambiguity locks us into focus. (Later, we realize that tinier, squatter boys and girls are the kids.) When a musician and a bear begin a snowball fight, the “snow” smears the lens (an early visual coup) and the bear’s wife steps up to lead her husband in a dance.

The Czech Year

Yes, dancing bears. Given this film’s freewheeling aesthetic, we can’t say for sure whether they’re anthropomorphic beings or villagers wearing festive costumes. Amid the growing terpsichorean frenzy, Trnka’s stomping, whirling bodies and adrenaline-lit faces keep escalating in the montage until the images change with each pounding musical beat. As merrily we roll along, Trnka filters Christian rites through backwater personalities and traditions. He transports us inside the dreams of Easter pilgrims: one fellow prays to score strikes at bowling. We wonder where all the negative energy goes. Then, in the midst of another rollicking number, a wizened old man starts to sing, in a modulated shout, about riding to war and leaving his sweetheart behind.

It’s like a pathos-laden precursor to the bittersweet opening of Up. In an extended flashback, the high points of a lifetime flash before us: the gallant horseman clomping off while his true love waves back at him, letters back and forth, cavalry charges and cannonades, the half-mistaken message that he’s been torn to shreds and lost. (The song is a high point of Vaclav Trojan’s versatile score. A master at blending folk themes, modernism, and “movie music,” in this film and Trnka’s other features, he’s like a Czech Prokofiev or Copland.) The sequence ends with the returning veteran staring at the bride and groom after a church wedding. His former fiancée has just married a dapper white-haired fellow. The vet looks at the man’s fine shoes, then at his own peg leg. This sequence stops the show.

Trnka’s features often establish a churning forward motion or a compelling beat, then daringly slip-slide away. Old Czech Legends tells a Mosaic epic with a scale and craft akin to War for the Planet of the Apes. Trnka stages a pulsating action opera using lanky, dramatic figurines vastly different from the jolly puppets of his previous piece of folklore. It commences with the Bohemian leader Cech leading his people to their promised land. It’s not easy for a filmmaker to summon tribal feeling in alien audiences, but when Cech climbs Rip Mountain alone to survey mind-expanding vistas filled with beasts, milk, and honey, we, too, feel like proclaiming, “This land is mine.” Cech asks his followers to name their new country. They call it Czech Lands, after him.

The Czech Year

Then, midway through, Libuse, the wisest daughter of Cech’s successor, becomes her people’s first female ruler. That’s when Trnka decisively alters the tone and pace of the film. His camera, like most of her subjects, stares at with wonder as she hands down judgments with a dynamic sort of serenity. Her authority gets shaken when a surly plaintiff questions her ruling on a land dispute and mouths off about being governed by a woman. Instead of rousing her supporters, she follows the advice of a female woodland spirit—and finds the right man to rule her patriarchal country.

No matter how disappointing for contemporary viewers, the quest to find this solid, fair-minded fellow proves to be enchanting. That doesn’t stop outraged female courtiers from igniting a gender-driven civil war. This film is full of dazzling blood-soaked vignettes, like a final-act battle between loyal Bohemians and a mad would-be conqueror that rivals the best of Welles, Ford, Olivier, and Peckinpah, or an indoor monster-boar hunt, with camerawork from the panicked beast’s point of view. But nothing is more moving than the surprising resolution of the rift between men and women. Even after the female rebels indulge in coldblooded trickery and torture, the male fighters readily engage their opposite numbers in a dance—and the male champion beckons the rebel leader to him. We’re witnessing the birth of gallantry, and Trnka’s instinct for gesture and movement makes it magical.

Because his material boasted national roots and he was hailed internationally as a pioneer, it looked from the outside as if Trnka could ply his craft without answering to Communist bureaucracies. Of course, a lot of his personal beliefs could fit comfortably within Marxist theory, if not practice. His 2-D/collage cartoon short, Springman and the SS (1946), is a hyperkinetic slapstick revenge movie about an anti-Nazi chimney sweep who fashions footwear from couch-springs that enable him to leap tall buildings with a single bound. He uses this superpower to taunt the Gestapo and the local quislings. Trnka’s savage anti-clerical short, Archangel Gabriel and Mistress Goose (1964), based on a story from Boccaccio’s Decameron, depicts a fraudulent, hypocritical monk hiding his lechery behind folds of shar-pei skin. He peers out through eyes so sunken he rarely opens his lids, recalling Leonardo Da Vinci’s studies of the grotesque. He poses as the Archangel Gabriel to bed a voluptuous parishioner.

The Hand

Trnka’s climactic short The Hand (1965) is a powerhouse anti-authoritarian parable about an artist—in this case a harlequin—obsessed with crafting a good pot for his house plant. He gets stymied by an enormous gloved hand willing to use any means necessary to prod him into crafting a sculpture of itself. Trnka fills this spooky, harrowing film with his firsthand knowledge of totalitarian regimes that shower moral weaklings with medals and co-opt rebels even after death.

It’s just as fascinating to see Trnka approach traditional escapist material with his playfully aware sensibility. In Bayaya, an expressionist gem of stop-motion medieval fantasy, a dead mother caught in purgatory comes to her son as a white horse and whisks him away to the king’s castle. To save three princesses’ lives he battles a gleefully malicious, hydra-headed dragon. When he cuts off three of its heads, it comes back with six, and when he slices those away, it returns with nine. Then the boy jousts in a tournament to win the youngest daughter’s hand. As this spectacular setpiece unfolds, a children’s ditty on the soundtrack mocks the knights’ sparkling livery and weaponry. The words allow us to drink in the thrilling thrust and tumble while chuckling over the comic waste of it all. It’s a telling expression of Trnka’s egalitarian ethos that the commoner hero and the princess end up happily ever after—in the boy’s modest home, not in the castle far away from his father.

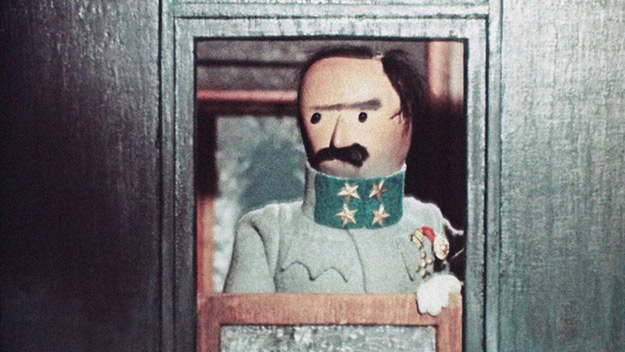

For me, the biggest surprise is Trnka’s blithe adaptations of three chapters from Jaroslav Hasek’s The Good Soldier Svejk. Who would have thought an animator would be the ideal interpreter for a slippery Czech grunt who survives World War I? Svejk, a self-admitted loon, is less idiotic than any rational war machine; Joseph Heller confessed he couldn’t have written Catch-22 without first reading Svejk. Critics have argued over the character’s status as a genuine dolt or a put-on artist.

The Good Soldier Svejk

Trnka, basing his designs on Josef Lada’s enduring illustrations, limns Svejk as an inscrutable adult cherub. His doughy affability masks a strong survivor’s instinct deep inside. His smile isn’t just his umbrella—it’s his armor, too. His tendencies to launch into digressions that exhaust his commanding officers (illustrated here in witty black-and-white cutout cartoons) or to overturn commands by following them too literally, register as the sort of adaptive mechanisms we read about in Darwin. Except here, the outcome is survival of the unfittest. He’s consistently humorous because he doesn’t know he is funny at all. Trnka makes Svejk’s few affectations both risible and alarming: his favorite march, for example, is a goose step. That’s especially upsetting because (as in Hasek’s book) the fellow cornering the black market on liquor is a Jew in caftan and side-curls.

Trnka’s legacy ultimately rests on his gifts as a world-builder and fabulist. At that, he’s simply nonpareil. As an introduction to tales from Shakespeare, parents should substitute his compact version of A Midsummer’s Night Dream for the Charles and Mary Lamb version. Trnka stays true to the story of lovers who switch affections under the influence of the woodland fairy king Oberon, who hopes to punish the misbehavior of his beloved Titania with the help of Puck, his sprite co-conspirator. Trnka also plants his own felicitous touches everywhere. Among the humans, Trnka specifies that one rival lover is a soldier and the other a musician—so the two fight sword against flute. In the supernatural glade it’s sensational to see an array of dancing blooms and acorn-cups, or small, fluttery insects forming a coat of many colors for Titania.

Trnka lavishes affection on the play’s low comics—the amateur actors who perform the tale of the doomed romantics Pyramus and Thisbe at the nuptials of their king Theseus and his Amazon queen Hippolyta. In Trnka’s version, Puck’s spells cause the royals to take their efforts seriously. Trnka miraculously conveys the whooshing emotion that ripples through an audience at the tragic climax. The final silhouetted dance of these infectiously innocent players caps a masterpiece of animated choreography.

The Emperor’s Nightingale

The Emperor’s Nightingale is a masterpiece of another kind. It’s a work of poetic mechanics. Those who’ve seen the widely distributed version with a Boris Karloff voiceover should seize this opportunity to view the original film fresh. Without any unnecessary verbiage, we can savor how buoyantly, in his live-action framing tale, Trnka sets up the objects in a sickly rich kid’s bedroom. This lonely, cruelly sheltered child reconfigures his possessions in a fever dream based on Hans Christian Andersen’s classic story about a Chinese emperor and his regimented court. The toy sailor attached to a bag containing a bouncing ball becomes a real sailor (that is, a puppet sailor) in his dream, while the ball gets transformed into the hot-air balloon that flies the seaman into China. A lace furniture cover with a pattern of decorative cutouts turns into a people-scape of the Imperial City, the faces of the emperor’s subjects filling each hole.

In Trnka’s re-imagining of Andersen, the emperor himself is a poor little rich boy, too. He follows a strict regimen of indoor mechanical diversions, like playing with glass swans that swim on a mirror-glass pond. These keep him occupied within the Imperial City, far from untrammeled nature. Then a book the sailor leaves behind enraptures him with descriptions of a nightingale’s enchanting song. His courtiers locate this creature, never before seen in court, in a dark forest by the deep sea. Back in the city, the birdsong’s beauty, redolent of the green wood and real life, cuts the emperor to the quick. The movie becomes a battle between this living thing’s unselfconscious art and the emperor’s soulless distractions, which eventually include a wind-up version of the nightingale.

The film triumphs because Trnka draws equal inspiration from the court’s ingenuity and the nightingale’s earthy lyricism. It’s a perfect launch pad for the two sides of his genius. His movies are so bracing because their puppet universe pierces into or rebounds off the real one.

The Puppet Master: The Complete Jiri Trnka runs April 20–25 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Stills courtesy the Czech National Film Archive.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and a contributor to the Criterion Collection.