Deep Focus: Minions

In Minions, the prequel to the Despicable Me movies, evil Scarlett Overkill describes her mini-henchmen as “pill-shaped miracle workers.” Actually, they’re more like petite yellow projectiles. With knock-’em-dead burlesque instinct, that’s how directors Pierre Coffin and Kyle Balda deploy them throughout a cock-eyed “origin story” that goes from all way back to Creation to “42 B.G.” (That is, 1968 A.D., 42 years before they first appeared with Gru, their one true master, in Despicable Me.) When the Minions enter 1960s New York and then Swingin’ England, they become DayGlo catalysts for tie-dyed comical destruction.

In an inspired introductory sequence, the Minions emerge with a roguish group personality from hazardous prehistoric seas. They’re tremendously engaging as they swim, wade, trudge and scamper through ocean, sand, tundra, and ice. As a tribe they plow ahead in hysterically hyperactive herky-jerky movements. What makes it all so distinctive is that Coffin and Balda individualize each one with an array of split-second double takes and rapid-fire ooohs and aaahs. They’re like Little Rascals on uppers.

The Minions’ two defining characteristics are a potent herding instinct and an unstoppable drive to follow the most potent and wicked villain in their sights. These chattering, easily distractable little guys embrace what they should fear, be it a Tyrannosaurus rex or a Neanderthal. They are eager to become part of any master predator’s team, including Dracula’s. Part of their subversive humor— and one reason they strike such reverberating chords with children—is that, like wayward kids, they mistake treachery and egotism for strength. But their neediness, loyalty, and skittering energy make them infectiously entertaining and appealing.

Though “minions” are by definition servile, disposable underlings, in Brian Lynch’s script these Minions work in mysterious ways. Their best efforts to serve wicked masters result in the bad guys’ downfalls. (In Despicable Me and Despicable Me 2, their enthusiastic allegiance to Gru helps bring out the good in that good-bad guy.) They’re like the wind that blows away the chaff, and they operate en masse with the sweep of a farcical hurricane.

Why has no comic artist before Coffin fully exploited the humorous undertones in the word “minions?” Geoffrey Rush relishes it in his narration, making it sound like a tangy compression of minced onions. Even Coffin and his original co-director Chris Renaud must not have realized that these eternally immature hedonists would become mighty mites at the box office. In Despicable Me, Gru brushes off the questions of who they are and where they came from simply by saying they’re his “cousins.”

Happily, in Minions, their moody mouths and goggled eyes (some are Cyclops, some Biclops) are expressive enough to anchor their own slaphappy epic. And their gibberish language, a United Nations of nonsense syllables, never fails to tickle the audience’s ears. Their dialect might stem in part from Coffin’s own background (his father is French, his mother Indonesian), but it also suits the collaboration between the Illumination Entertainment animation team in Santa Monica and the Illumination Mac Guff animation team in Paris. One of Coffin’s major contributions is voicing all the Minions himself. In the orchestrated whimsy of their dialogue, he sprinkles recognizable words and phrases like “si,” “gracias,” “mazel tov,” “buddies,” “thank you,” and “banana” (the Minions’ favorite food) among indecipherable grunts, riffs, and expletives. When faced with a portrait of Queen Elizabeth (voiced by an absolutely fabulous Jennifer Saunders), one heroic minion happily exclaims: “La cucaracha!”

The origin story Coffin and Balda tell in Minions is part haywire road movie, part James Bond blowout, and part slapstick destruction orgy. In a masterstroke that precludes any embarrassing questions about why Minions didn’t grow attached to Hitler, Mao, or Stalin, the creatures bollix up their relationship to Napoleon and, in flight from his ticked-off troops, race all the way to the Frozen North. There they build a snow-and-ice city in a massive cave and are happy for roughly a century and a half.

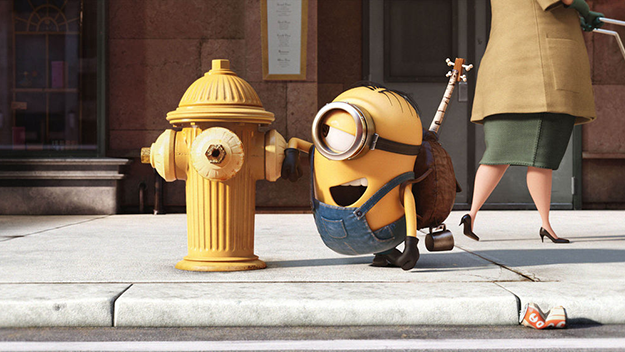

Once past the euphoria of founding their own fun-loving society, they realize how much they need a boss. They question their reason for being and line up for a psychiatrist. They grow sad and listless in tableaux as hilarious as Steve Martin and Dan Aykroyd acting like depressed Wild and Crazy Guys on Saturday Night Live. Only a new and more durable boss can save the Minions from pop-less ping-pong, somnolent soccer, and cheer-free cheerleading. Three Minions set out to find a new master villain so they can play Follow The Leader once again. Kevin, as determined and hopeful as the vertical thatch of hair on his head, keeps both of his eyes focused on the search. Stuart, who is all appetite, trains his one eye on guitars—to him they’re “mega-ukuleles”—when he’s not ogling “girls” (to him, yellow fire hydrants look like nubile females). Bob, the fearful innocent, goes nowhere without his teddy bear but makes unlikely friends (like a sentimental rat) and scales improbable heights when he must save his comrades.

After a trek across continents and oceans that, uproariously, puts them at the brink of disaster—a famished Stuart hallucinates that Kevin and Bob are bananas—this unlikely trio arrives in Manhattan and receives a crash course in urban culture and counterculture. They act a bit like hippies themselves, appropriating three sets of blue-jean overalls from a clothesline (thus, the Minions’ look is born) and squatting in a department store after hours. Snuggled up in a showroom bed, they experience the wonder of rabbit-ears TV, flipping past The Saint and Bewitched to tune in on The Dating Game. In one of the film’s many offhand strokes, the male contestants bear names and personalities similar to their own. When they lose the signal and try to regain it with a makeshift antenna, they stumble on a renegade channel that broadcasts information about Villain-Con, the convention of their dreams, based in pre-Disney Orlando. They’re soon hitching to the Sunshine State, in hopes of signing up to serve Scarlett Overkill (Sandra Bullock), the breakthrough female super-villain. With the help of the Minions and her gadget-maker husband Herb (Jon Hamm), Scarlett aims to steal Queen Elizabeth’s crown—and assume her throne.

All the vocal artists—including Steve Coogan as a mad scientist who outsmarts himself and as a deceptively doddering Tower of London guard—perform in character with gusto. Hamm has more fun on the soundtrack than he’s ever had in front of movie cameras, playing Herb, a soigné, smarmy pop-art aesthete who develops weapons and larcenous devices as tricky pieces of performance art. He savors the 1960s treasures that Scarlett has looted for him, including one of Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup cans. Herb thoughtfully explains to Bob: “We stole that because finally someone expressed my love of soup in painting form.”

The 1960s were all about breaking boundaries, and Minions is, too. What’s most anarchic and ineffable about the humor is the way Kevin, Stuart, and Bob connect to the period’s explosive pop art, whether they’re applying their own vernacular to the Monkees’ theme song or trying to emerge from a manhole cover in Abbey Road just when the Beatles are crossing the street. The soundtrack is evocative and droll, whether it’s playing The Turtles’ “Happy Together” as single-cell Minions swarm together for survival in the primordial muck, or The Rolling Stones’ “19th Nervous Breakdown” when Kevin, Stuart and Bob enter cacophonous New York, or The Doors’ “Break on Through to the Other Side” as they cross the threshold into Villain-Con.

The animation often percolates like a crack-up period collage. The opening sequence neatly establishes running jokes about the food chain while evoking Yellow Submarine. Scarlett Overkill’s bedtime story about three little pigs (the Minions) and a Big Bad Wolf (herself) unfolds in cut-out and puppet animation that pays madcap homage to legendary puppet animators of the 1950s and 1960s, like Jiri Trnka, while Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf plays on the soundtrack.

Still, the movie wouldn’t work, even as a jamboree, were it not for Coffin and Balda’s understanding of their seemingly inscrutable characters. Kevin’s would-be manliness and covert adolescent joshing, Stuart’s fantasies about becoming a star, and Bob’s prepubescent exuberance inform the action even when it becomes frantic. As meticulously as Harold Lloyd staged his mounting of a skyscraper’s clock, these directors set up an epic piece of slapstick involving a funeral wreath, a bee, a climb up a wall, and a leap onto a chandelier. They wring wit from changes in scale the way Jerry Seinfeld tried to in The Bee Movie. The sequence of Kevin assuming a gargantuan form goes on too long, but it clicks when he passes a tearoom full of newly arrived, normal-sized Minions scarfing down their scones.

Coffin and Balda are so generous that they spice up the end credits with vignettes of the Minions bonding with a very young Gru. They save the very best for the very last: a Minion rendition of the Beatles’ “Revolution” that becomes a curtain call for the entire cast and an excuse for one more giant food-chain joke. In its own helter-skelter way, Minions achieves a loony symmetry. It starts with evolution and ends with revolution.