Deep Focus: Mary Poppins Returns

Mary Poppins Returns propels the Banks family and its nonpareil nanny on so many gusts of poignant, humorous invention that it leaves not just the cast but any non-Grinch audience floating merrily in mid-air. The film takes place during “The Great Slump” (better known as The Great Depression) but the director, Rob Marshall, establishes a nifty, resilient tone as Jack (Lin-Manuel Miranda), a lamplighter, cycles through London at dawn to turn down gaslights. Jack insists on celebrating “the lovely London sky” though food queues and urchins line the streets in a sooty, lowering atmosphere. As embodied by Miranda with an incendiary sweetness that sets off sparks in song and dance, Jack senses the inner vitality that will revive the city’s families and change their fortunes. Marshall’s frequent cinematographer-alchemist, Dion Beebe, who also shot Chicago (2002), uses his powers of suggestion to conjure hidden beauties in morning mists and early lights.

Deftly, playfully, this opening number, which ends right where it should, at 17 Cherry Tree Lane, sets up the film’s pop metaphors and images, including lamps as magic lanterns of fellowship and cityscapes as realms of wonder. Jack breezes through the picture’s cheery advice for perplexed families: search for buoy lights and beacons, savor momentary joys, shift points of view to gain worthier perspectives (especially, “look up!”), and hold and grasp the people you love—who they are and could be. He doesn’t need to say “Keep smiling through”—Miranda personifies that, effortlessly.

Rooted in Emily Blunt’s witty, assured, protean Mary Poppins, screenwriter David Magee and Marshall and John DeLuca (who co-wrote the story with Magee) fill out these motifs with talking cartoon animals, an army of “leeries” (slang for lamplighters), and vivid Cherry Tree Lane eccentrics, including the cannonading Admiral Boom (David Warner takes over, perfectly, from Reginald Owen), whose obsession with time clicks into the clock-stopping climax. The unrestrained adventures that Marshall and DeLuca choreograph into novelty acts, show-stoppers, hilarious tableaux, and a little white-knuckle action revive the grownup Banks kids—widower Michael (Ben Whishaw) and workers’-rights activist Jane (Emily Mortimer)—and open up metropolitan marvels for Michael’s flock: Annabel (Pixie Davies), John (Nathanael Saleh), and Georgie (Joel Dawson). Georgie inadvertently pulls Mary Poppins out of the air on a kite. Jack, a protégé of and honorable successor to Dick Van Dyke’s “Bert,” is her soulmate.

The result is an un-coming-of-age movie. When we first meet Annabel and John, they more or less run the house for their distraught dad and addled housekeeper Ellen (Julie Walters, uproarious as ever). They’re premature adults who grow impatient with their daydreaming younger brother Georgie. Under Mary’s delightfully oblique care, they embrace their youth, while Michael and Jane, who has given up on romance, rediscover theirs. (Georgie, Mary’s new favorite, comes into his own.)

Blunt’s version of the character as a brusque agent of rejuvenation is miraculously fresh and funny. Blunt hews closer to the tangy, fractious governess of P. L. Travers’s books than to Julie Andrews’s warm, gleaming paragon. Blunt gives Mary a Mona Lisa smile that keeps everyone guessing (except for close pal Jack) and the killer timing of a putdown artist who has decided to use her gifts for good. The kids soon cotton to her staccato éclat. She wins us over immediately with her mixture of irritated and amused authority and her enigmatic cool. Her virtuoso self-consciousness works like catnip on youngsters and proves to be alluring: when she shoots herself an approving grin in a mirror, is she revealing her self-satisfaction or making sure her persona is pasted on tight? Blunt puts a glamorous twist on Poppins’s omniscience and omnicompetence—the more talents she unveils, the more appealing she becomes. The performer partners with her director to keep the action toned and limber. Blunt’s Poppins wins a giant laugh even when she halts a sequence that’s gone on a tad too long.

While following the Mary Poppins template, this movie echoes everything from Busby Berkeley movies to Carol Reed’s Oliver! “Can You Imagine That?” plunges Mary and her charges into Finding Nemo’s digital seas, where they talk and sing sans snorkels. Marshall’s masterstroke is to people the deep with figures from the children’s lives, delivering both an Esther Williams water ballet with diving dolphins and a joyous variation on those giddy Wizard of Oz moments when Dorothy sees the family farmhands row a boat through a tornado. The leeries’ “Trip a Little Light Fantastic” mirrors the chimneysweeps’ “Step in Time” from the original Mary Poppins, but Marshall kicks it off with Bob Fosse–like flourishes, then segues into lamp pole-dancing, some Stomp-like motifs, and rambunctious synchronized cycling that’s unexpected and invigorating. It culminates in rhyming “leerie talk” that puts a Cockney-versifying stamp on rap.

Marc Shaiman skillfully weaves motifs from the earlier film’s Sherman Brothers score into the orchestral music, eliciting nostalgic pangs while putting over the idea that bygones should be pleasurable despite being tinged with sorrow. His and Scott Wittman’s apt and charming songs strike alternately plain and fancy notes. “Have a pot of tea, mend your broken cup,” Jack advises at the start, and though Blunt’s Mary rolls off tongue-twisters as brilliantly as her predecessor, Dame Andrews, she’s equally superb at being cryptically silly and emotionally direct. She’s as much Mother Goose as Mary Poppins when she croons that a lost dish and spoon could be “playing hide and seek behind the moon.” Shaiman and Wittman’s work ranges from touching and subtle to gleefully bombastic: it all fits Marshall’s grand design.

Come in hoping for a smart, affectionate romp through Mary Poppinsiana and you’ll be rewarded. Arrive without expectations and you’ll be surprised at how moving an experience this musical comedy can be. On its own pop terms, the movie transmits a genuine artistic response to financial hardship and familial heartbreak. Whishaw is quietly sensational as Michael, a struggling artist striving to pay the bills as a part-time teller. Now his employer plans to foreclose on his house. Whishaw’s eyes are as expressive as his voice when Michael, searching for his misplaced bank shares, opens his late wife’s musical jewelry box and sings “A Conversation.” He commingles longing and grief so consummately that the song becomes an instant heartbreaker—for a woman we never see. He ends “My question, Kate, is ‘Where’d you go?’”

Mary answers when she croons his children to sleep with the elegant lullaby “The Place Where Lost Things Go.” What Marshall salutes and Mary advocates for each Banks, big and small, is the healing power of creativity. Dreams are where what’s “lost is found.” The bank chief (Colin Firth) doesn’t ooze evil merely because he’s a cutthroat capitalist, but also because the pseudo-rationality of his profit-and-loss tables—his banker’s equivalent of keeping the trains running on time—curtails any hint of sympathetic imagination. It’s a kick to see Firth offer a clever caricature of a superficially suave, disgustingly glib professional. (One fears these days he might be taken as a role model.) Jeremy Swift and Kobna-Holdbrook Smith make a superb smarmy/sympathetic lawyer team as two of his brutalized underlings.

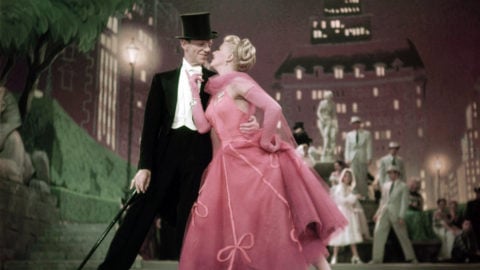

For the film’s deliriously intricate 2-D cartoon segment, Firth, Swift, and Smith also give voice to a wolf, badger, and weasel, respectively. In a glorious tribute to the “Royal Doulton Music Hall” (and an update to “It’s a Jolly Holiday with Mary”), Marshall combines “total theater” with “total movie.” (Wagner had a name for it: Gesamtkunstwerk.) Jack and Mary and her charges leap into the pastoral scene painted on their mother’s “priceless” china bowl to fix a decorative detail broken during a nursery tussle. Marshall deploys old and new techniques with a soulful seamlessness for this heady jaunt through a countryside filled with English-speaking mammals to an entertainment palace catering to all species. Costume designer Sandy Powell, a whiz throughout, puts the humans into garden-party garb and actually paints their outfits to suit the cartooning’s eye-popping colors.

Combined with the uncanny contributions of traditional cel artists, digital compositors, and production designer John Myhre’s crack team, the resulting 2-D animation is not “fantasy come to life”; it’s “life come to fantasy.” To keep it all supernaturally natural, Marshall stitches in casual bits that must have absorbed weeks of labor, like Georgie swapping his cap for a coachman’s top hat. (The never-disappointing Chris O’Dowd plays Shamus, the coachman.) Recognizing the kids’ shock when they hear him speak, Shamus puts them at ease by saying, “I know—I’m Irish.” (Well, he’s part setter and part poodle.) The sequence climaxes with the rousing “A Cover Is Not the Book:” Blunt and Miranda channel their inner vaudevillians with split-second sass that keeps their performances front and center while the scenery changes with droll fluidity. Miranda, in particular, pulls off some of the snappiest movie-musical patter since Robert Preston in The Music Man.

What Marshall does in this sequence applies to the movie as a whole. He places familiar faces and patterns into a wonderful state of flux. That’s true whether he’s preparing for the unexpected entrances of two special guests (since the word is out by now: Dick Van Dyke and Angela Lansbury), or working in a boisterous specialty number for an uninhibited Meryl Streep as Mary’s distant Slavic cousin Topsy, a Ms. Fixit whose world “turns turtle” every second Wednesday. Marshall took inspiration from the “Topsy Turvy” chapter of Mary Poppins Comes Back, but he revamped it heavily enough to include a cunning poke at Streep’s penchant for accents.

Even Marshall’s choice of season adds to the vitality. The story unfolds during the early days of a cold spring—Michael sings, “The snow has left the lane, but the cherry trees forgot to bloom”—and ends in an orgy of blue skies and pink blossoms. This warming trend reminded me of Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “A Cold Spring,” which starts with trees hesitant to show their leaves and culminates with fireflies “on the ascending flight, drifting simultaneously to the same height—exactly like the bubbles in champagne.” At the close of Mary Poppins Returns, we’re ready to pop the bubbly.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.