Deep Focus: Les Parents terribles

The timing couldn’t be better for reviving Cocteau’s least-seen masterpiece, Les Parents terribles: a peerlessly witty, imaginative, and haunting tale of volatile emotions in a chaotic family. The situation of penniless 22-year-old Michel (Jean Marais), living in his parents’ apartment, under the sway of his diabetic, ultra-possessive mother Yvonne (Yvonne de Bray), should connect with American audiences in an age when more young adults live with their parents than with a spouse or partner. What makes the film so exciting is how briskly and persuasively Cocteau takes everything to extremes. Yvonne reacts to Michel’s news that he’s become attached to a 25-year-old woman by flinging open her bedroom window and trying to summon the police.

In conversation with Michel’s sane, pretty lover, Madeleine (Josette Day), his Aunt Léo (Gabrielle Dorziat), who really runs things at home, muses that a person can’t know his or her own deepest thoughts. “It’s Greek to me,” she says—and we think, “Of course it’s Greek: it’s Oedipus Rex.” When Arthur Miller tries to mix classical tragedy with 20th-century melodrama in A View from the Bridge, he delivers clunky, inflated social realism. When Cocteau does it in his play and screenplay of Les Parents terribles (first presented on the Paris stage in 1938, filmed in 1948), the result is divine, vaudevillian tragicomedy.

This movie’s family has been labeled “bourgeois,” but Aunt Léo explains why they’re not. Only she has any money, and except for an occasional charwoman, they neither employ servants nor maintain an orderly existence. Yvonne’s husband, Georges (Marcel André), a would-be inventor, has ceded his household authority to Léo and his rights of marital affection to Michel. Yvonne, when she was 22 or 23, wooed Georges away from Léo, who was engaged to him. Yet ever since Yvonne gave birth, she’s had eyes—and arms and lips—just for her son. Stunningly handsome, Michel has grown so sloppy and clumsy that he repeatedly loses his shoes or cracks his teacup.

Yvonne’s belief that they belong in an elevated milieu may be her most bourgeois quality. This family’s plight extends beyond class. We view their perversity and ineptitude as outré examples of what can happen wherever and whenever a clan collapses inward. Les Parents terribles is the ultimate dysfunctional-family film because Cocteau clarifies how this group organism actually does function: in warped patterns. Léo derives pleasure from seeing how far clutter and filth get out of hand before her sister and brother-in-law realize that dirty laundry has piled into mountains and the bathtub has clogged. (Then she’ll fix it.) Yvonne is happy as long as she has Michel to herself. Until she explodes over his romance with an “older woman” (who’s three years older than he is), Michel delights in his state of arrested adolescence: even Madeleine mothers him. And Georges putters away in his crackpot study, striving to create an underwater sub-machine-gun.

Léo guesses that Georges, too, has been having an affair. Under an assumed identity, he has—to Madeleine, who had no idea her sympathetic sugar daddy was Michel’s dad. Georges, who didn’t know she was Michel’s gal, now realizes that she plans to dump him. (Madeleine says she never knew true love before Michel, and we believe her.) Can anyone except Léo survive these tremors?

In the film’s fleet 105 minutes, Cocteau achieves the soul-rattling black comedy and drama of a Eugene O’Neill epic. The harrowing intimacy of Les Parents terribles surely stems from its roots in Cocteau’s life. The project started when Marais, Cocteau’s lover and protégé, tired of parading his physique in action roles or costume plays (and being derided by critics as a pretty boy), asked him to create a modern role that would exploit his acting more than his looks. Cocteau then drew on the demented bond between Marais and his mother, who grew violently jealous of anyone who got near her son. Cocteau’s closeness to his own mother became part of the dramatic mix, along with elements from the family lives of other lovers and friends. Georges was the name of Cocteau’s father, who fatally shot himself when his son was nine. Cocteau’s first and rare “female passion” was another Madeleine. The mother became “Yvonne” because he had envisioned Yvonne de Bray in the role.

Parisian audiences who made the 1938 stage production a sensation were in for a surprise 10 years later. Once a painted curtain rises, Cocteau tosses away proscenium conventions. Cocteau told interviewer André Fraigneau, “I had set out to do three things: firstly, record the acting of an incomparable cast; secondly, walk among them and look them straight in the face, instead of contemplating them at a distance on the stage; thirdly, peep through the keyhole and catch my wild beasts unaware with my tele-lens.”

His camera reacts not merely to the domestic misbehavior of his “wild beasts,” but also to his own tender shock and awe at their alarming behavior. We watch the film as if by Cocteau’s side, able to discern the characters’ fleeting impulses and craftiest machinations. We grow as close to them as to eccentric cousins. The result is a waking dream—make that “waking comic nightmare.” Cocteau was never more of an instinctive virtuoso than he is in Les Parents terribles.(This film boasts the most persuasive swooning scenes in movie history.) Working with cinematographer Michel Kelber and camera operator Henri Tiquet, Cocteau develops a subtle yet potent visual style that enables editor Jacqueline Sadoul to cut together a sustained surge of emotion-charged images.

At first we fear Cocteau may go for baroque, since he starts with a close-up of Georges in his scuba mask and, a bit later, cuts to an overhead shot of Yvonne collapsed over her sink, near her insulin needle. But most of the time, the camera reacts like a steady seismograph to the family’s emotional temblors. Cocteau executes modest pans, tilts, push-ins and pullbacks, then rapidly shifts angles to catch oscillating waves of feeling. At peak inspiration, he frames Michel’s chin and cheek against Yvonne’s temple, as he confesses his love for Madeleine, facing the camera. We see his boyish delight as he looks upward toward some imagined amorous paradise, and his mother’s spurned-woman sorrow as she stares straight ahead. Then he rests his head on hers and Cocteau pans down to show only his moving lips and his mother’s panic-stricken eyes. Isolated, it’s an avant-garde photograph. In the flow of the movie, it’s a brilliant audiovisual anti-catharsis—a moment that stokes emotion to the breaking point but never releases it.

The ensemble work throughout is immortal. Cocteau wrote of his Yvonne and Léo, “In the tennis match between Madame de Bray and Madame Dorziat, in which almost every ball is sliced or placed on the line, you are amazed by their speed and may wonder who holds their racket best. One plays with her guts, the other with her head, and this makes them incomparable in roles which demand precisely that difference in style.” Baggy-eyed and blowsy but still proud, de Bray gives a gutsy, galvanizing performance. She’s got the wavering vulnerability of late-phase Judy Garland, but she never loses focus. Her intuitions magnetize the tiniest details. When Yvonne realizes that Michel may enter her room, she reaches for her compact mirror.

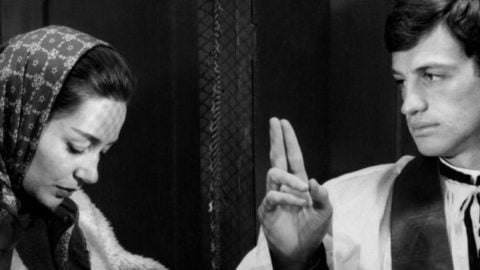

Dorziat’s sharp, slippery, sometimes Sphinx-like Léo acts like a referee in this film’s domestic form of Darwinism—survival of the emotionally fittest. After offering to help Madeleine, Dorziat choreographs a palm-waving, finger-wagging hand gesture to dismiss the gal’s weepy gratitude. As elaborate as any dap, it’s an outward sign of Léo’s buried intricacy. Marcel André conjures an erratic force as confused, angry, self-pitying Georges. When he bangs the dining-room table, a table-leaf pops up and nearly smacks Yvonne. (Cocteau milks the gag.) Josette Day, Cocteau’s Belle in Beauty and the Beast, conveys Madeleine’s clean solidity from the moment we see her scrubbing Michel’s back as he celebrates their romance in her tub.

In all his exuberance and mood-swinging madness, Michel could be the precursor of mixed-up kids in 1950s family dramas. But Marais plays him with verbal speed and physical flair instead of the usual pregnant pauses, stuttering diction, and unconscious scratching of body parts. He fuels his performance with classical gas. Whether he’s uninhibitedly cuddling with Yvonne or imagining a rosy future with Madeleine, he’s like a modern-dress version of the “sanguine” Shakespearean humor of red-blooded adolescence. He picks up Léo and twirls her around in one of the rare impromptu dances that’s ever worked in a non-musical. It’s marvelous that he acted this part with such authority and panache a decade after creating it. His disarming smile and energy defuse any qualms either about his real age (35) or the play’s potential for petty, lurid melodrama. His re-creation of Michel is, as Cocteau wrote, “Great art.”

During its first international release, Cocteau complained that Les Parents terribles “is doing less well abroad than my other films. This is because the French language plays the leading part in it. The genius of the actors cannot overcome that difficulty.” Actually, they can.

Les Parents terribles opens May 25 at Quad Cinema.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and a contributor to the Criterion Collection.