Deep Focus: Jeff Bridges and Hell or High Water

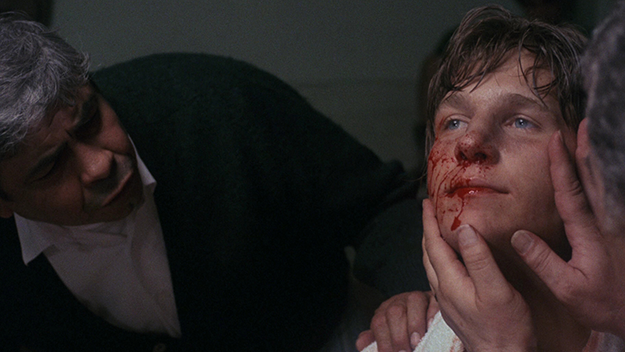

Fat City

Bold, intuitive actors who spend a professional lifetime in movies can achieve a style so unique and expansive that they elevate every scene they’re in. It was true of Burt Lancaster 30 or 40 years ago, and it’s true of Jeff Bridges today. Bridges has become his own kind of great American artist—the Westerner who embraces experience and exudes unpretentious, often humorous wisdom.

Bridges has been giving lived-in performances from the start, in Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show and John Huston’s Fat City, Lamont Johnson’s The Last American Hero and John Frankenheimer’s The Iceman Cometh. This California man—a son and brother of prime Hollywood talent (Lloyd, Beau)—has always possessed more technique than most big-screen originals as well as more range and versatility than peers enveloped in the mystique of “New York actors.” (Bridges logged three months at the Herbert Berghof Studio in Manhattan.)

Kenneth Tynan once wrote that “to be famous young and to make fame last—the secret of combining the two is glandular: it requires energy.” But it also depends on the depth of the indefinable something that makes a performer stand out in the first place: the quality called “star presence,” which in Bridges has been growing in magnitude and radiance for 40 years.

The Fabulous Baker Boys

Mid-career he made that presence felt in everything from noir-ish musical romance (Steve Kloves’s The Fabulous Baker Boys) to avant-garde Western (Walter Hill’s Wild Bill). Then he played “the Dude” in the Coen Brothers’ The Big Lebowski—a social dropout so euphorically wacked that we get a contact high just looking at him. No actor since Toshiro Mifune got more expressive mileage out of stretching his back or his hamstrings. Bridges gave the Dude a textured fuzziness that imparted a second-to-second emotional authenticity even to the Coens’ most jumbled, show-off action. He made the intangible tangible. He stayed grounded in reality even when his character got lost in the vapors.

Playing the Dude added a new imaginative freedom to Bridges’s formidable creative arsenal. He drew on it in all types of films and genres. In Seabiscuit Bridges kept the racetrack showmanship of a well-heeled Depression horse-owner front and center, while embodying the man’s magnanimity toward racetrack underdogs. In Iron Man, Bridges exerted an avuncular force as Tony Stark’s business partner Obadiah Stane: with his trademark head of hair shaved, the power in his face funneled into his eyes. They were as enigmatic as they were galvanizing. Rod Lurie told me in an email that when he convinced Bridges to do “President Jackson Evans” in Lurie’s political melodrama, The Contender, “He hugged me and said, ‘The Dude as President. Who’d have thought it?’” But rather than play him as a slacker pothead in disguise, Bridges translated his otherworldly power as an actor into the particular strengths of that character. With President Evans, Bridges gives us the Platonic ideal of Bill Clinton—marvelously instinctive and down-to-earth, principled, and shrewd, the life of the Party, the White House, and the movie.

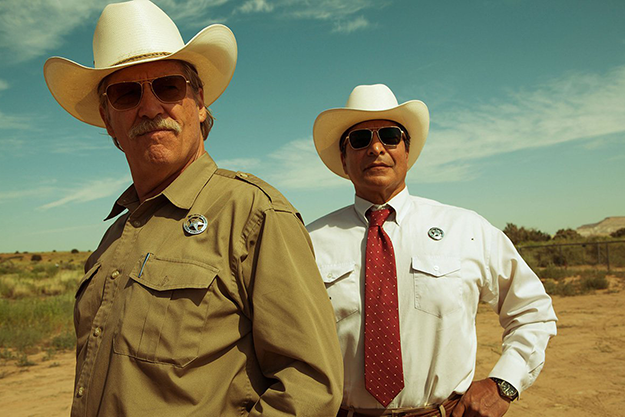

Bridges is the one undiluted delight in David Mackenzie’s Hell or High Water. He plays Texas Ranger Marcus Hamilton, a smart, engaged lawman, three weeks away from forced retirement, who deciphers the game plan of two men robbing a string of West Texas banks. Pulling his Indian-Mexican partner Alberto Parker (Gil Birmingham) into the hunt, Marcus hopes to lie in wait for them across the street from their next heist. As a portrait of a man with a playful mastery of his craft, I’d rank Bridges as Marcus with Picasso as Picasso in The Mystery of Picasso.

Hell or High Water

In a sense, there’s no mystery about what happens in this movie. Marcus sizes up the banks they hit in a small chain called Texas Midlands, and he recognizes that they’re smart for stealing untraceable bills from the tellers’ drawers. These banks haven’t yet properly rigged their new digital surveillance systems. Marcus may figure the thieves know that, too. He doesn’t say so, but Bridges’s shrewd silences and cracker-barrel stares can suggest anything. Marcus reckons that the robbers will keep hitting other Texas Midlands banks until they reach their cash target.

What is mysterious is how Bridges manages to go beyond the movie’s plot. In his immersed and immersive kind of acting, the angle of his slouch and the tilt of his head are as eloquent and startling as the unpredictable arc of a sentence by Mark Twain. He creates a comic essay about friendship from the way he slumps on a motel chair next to a six-pack and grouses about Alberto lying in bed and watching a TV preacher. (Birmingham partners him perfectly, with a hidden half-smile.) Bridges conjures a haunting tableau of homegrown brilliance as Marcus wraps a blanket around his torso and spends a night brooding on a porch chair. It’s like a seriocomic riff on Peter O’Toole’s T.E. Lawrence obsessing under the desert moon. Alberto deflects Marcus’s jovial racial jibes with some agile ageist gags of his own. True to their stoic brand of masculinity, these guys never stoop to direct expressions of their feelings. The actors build their relationship on two things: an unspoken bond of fraternal love, and the mutual realization that Marcus is almost always (pardon the expression) on the money.

Mackenzie proved that he knew how to key a film to the vivid mixed emotions of an inspired ensemble when he directed Ben Mendelsohn, Jack O’Connell, and Rupert Friend in the British prison movie Starred Up. He staged and cut the action to express their impulses and thinking. Apart from his splendid work with Bridges, in Hell or High Water he does an artful job of shooting the script, but he still can’t compensate for its schematic simplicity and glibness. He semi-stylizes the action to put it over. He keeps us inside the getaway car rattling away from a robbery so we buy that it won’t attract the police car crossing its path. He partially obscures our view of Toby beating on a gun-toting punk who goads him at a gas station, keeping his camera one car and pump-island removed. His work here is handsome and tactful, if not probing.

Hell or High Water

Taylor Sheridan, the screenwriter, who wrote the relentlessly scary drug-war movie Sicario, knows how to set the action in motion, and Mackenzie knows how to keep it rolling. But it goes down some well-worn tracks. At best the nonstop ranting against banks plays as rural black comedy. Sheridan has a dab hand with down-home humor: when Marcus asks some old-timers if they’ve been sitting at a diner for a while, one answers, “Long enough to watch someone rob the bank that’s been robbing me for 30 years.” At his peak, Sheridan contributes a bad-waitress scene that may become a classic, like the one in Five Easy Pieces. Too bad Sheridan pegs his crucial characters, the hold-up men, to a sociological specimen board. The concepts of poverty as a “poison” passed down through generations, the cowboy way of life as an anachronism, and family abuse as an unalterable cycle of violence utterly define the bank-robber brothers, Toby and Tanner Howard (Chris Pine and Ben Foster, respectively).

Tanner, the wild one, is an ex-con with a bloody past that includes the murder of their brutal father. (Tanner told police it was “a hunting accident,” though the killing occurred in a barn.) He’s conventionally explosive; Toby is conventionally implosive. While nursing his dying mother, this dour, determined divorcee hatched his robbery plan to cover her debts to the Texas Midlands banks and make her unexpectedly oil-rich ranch a legacy for his own two sons. (It is enjoyably ironic that he aims to pay the banks with their own money.) Foster peppers Tanner’s menace with madcap exuberance. Pine threads scarlet rage into Toby’s grey demeanor. But the writing stymies them. They strive to generate electricity in the spaces between the lines, but it gets lost in the dead air.

An actor turned screenwriter, Sheridan sacrifices depth and consistency for effect. The super-cautious, hyper-rational Toby risks his freedom by virtually confessing his crimes to his older boy. (Toby tells his son to believe “everything” he might hear about his uncle and his dad.) A tense coda rests on the far-fetched notion that if Tanner is linked to the crimes, Toby won’t be. Sheridan needs that coda to hammer us with his idea of moral ambiguity and his insistence on frontier family values. He wants us to reconsider how glad we are that the Howards stick up—and stick it to—the bank. But there’s nothing left for us to learn about the Howards once we grasp their socio-psychological profiles. Sheridan parses out the information about Toby’s ex-wife and kid and his and Tanner’s mom and dad while the two men do their dirty work, go on the run, and live and die with their choices. It’s less a journey into the heart of darkness than a game of follow-the-dots.

Hell or High Water

“A large part of acting is just pretending,” Bridges told London’s Daily Telegraph in 2005. “You get to work with these other great make-believers, all making believe as hard as they can.” In Hell or High Water, Pine and Foster try “making believe as hard as they can,” only to come up empty. But Bridges uses his own creative vision to refresh the stock role of a canny old lawman—and he’s so at ease in his talent he doesn’t look like he’s trying at all. Isn’t that what presence is all about?

Has any other Oscar performance looked as effortless as Bridges’s portrayal of an alcoholic country singer in Crazy Heart? He walked audiences through a maze of existential confusions without missing a step. Here he uncannily creates a life-size Western hero from the marrow out. He alone makes Hell or High Water worth seeing.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.