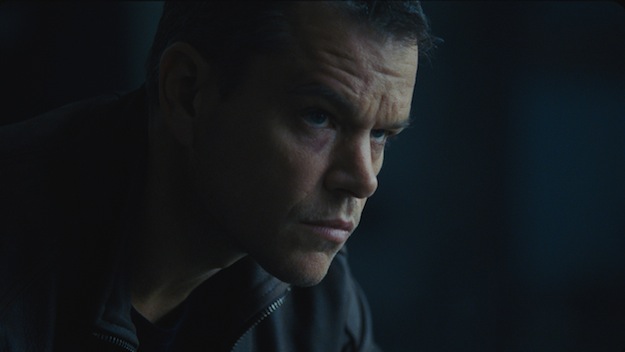

Deep Focus: Jason Bourne

With Jason Bourne, Matt Damon and director Paul Greengrass return to the rare Hollywood franchise that’s equally brainy and brawny, and once again they try to engage adrenaline addicts and high-end espionage fans alike. A visceral workout with several clever nods to current events, this entry gives series fans their money’s worth as former CIA agent Nicky Parsons (Julia Stiles) and current CIA digital intelligence guru Heather Lee (Alicia Vikander) introduce Bourne, now living as a bare-knuckle fighter based in Athens, to the part brave, part cowardly new world of high-tech surveillance.

The movie starts out with grand ambitions, then descends from macro-content to micro-content to nano-content as it pits Bourne against the favorite hit man of CIA director Dewey (Tommy Lee Jones), another super-skilled assassin known only as “the Asset” (Vincent Cassel). While the vehicular mayhem grows, our guts clench but our minds wander. Is it a sign of series exhaustion that the Bourne films have started to make me think of subtitles from Friday the 13th movies? There’s Jason Lives, The New Blood (Jeremy Renner in The Bourne Legacy), and Jason Takes Las Vegas (okay, the FTT13 movie was Jason Takes Manhattan). Are we doomed to see Jason Goes to Hell and Jason X? The filmmakers could go full cartoon with a slam-bang crossover, Jason v. Jason.

It’s easy to grasp the appeal of Jason Bourne, the weaponized human being who rediscovers his soul. First developed from Robert Ludlum’s novels by the original writer-director, Doug Liman, he’s a perfect fantasy action figure for confusing times because he makes ambivalence dynamic. Throughout the series, he wants to tamp down his killer instincts and retire from the assassination game. What keeps pulling him back are the chances of wreaking revenge on culprits who persist in killing his loved ones and the prospects of discovering what turned an honorable soldier like himself into a conscience-less assassin.

At the end of the original trilogy, Bourne seemed to have learned everything about his origins and exacted enough retribution on evildoers to go off the grid with a clean slate. (In the fourth movie, writer-director Liman simply set up a parallel track with Renner as faux-Bourne “Aaron Cross.”) At the beginning of Jason Bourne, Parsons, who’s been working with a Julian Assange–like figure, hacks into the CIA and downloads its black ops. She discovers information about Bourne and his father that (she thinks) might assuage any guilt Bourne still feels about volunteering for a program that made him an executioner. Soon Bourne’s search for this skeleton key to his origins gets wrapped inside another quest for justice—and both the folksy, sardonic Dewey, and Dewey’s Asset are determined to eliminate him before he can punish his enemies or air embarrassing revelations.

Vikander’s Lee occupies the space between Bourne and Dewey. She’s ambiguous to the end because Vikander makes a fascinating frenemy. Dewey relies on Lee’s expertise for his shady dealings with a Silicon Valley entrepreneur, Aaron Kalloor (Riz Ahmed), who grosses billions with a platform that promises to combine total privacy with unprecedented capabilities for compiling personal data. Whatever Lee’s own buried agenda, she believes she can bring Bourne back into the fold, as long as she can persuade him of basic changes in the Agency.

It’s too bad that Greengrass’s warning about the convergence of government information-gathering and social media is like a foghorn—he blares it out, then it gets lost in murk. What’s more like a dog whistle is the way he renders a faltering global economy: he stages one chase through a fiery mass demonstration in Athens (based on the 2012 protests against austerity) and another through high-rolling Vegas. Neither theme feels germane to the story, because Bourne isn’t crusading for government transparency or against the international financial elite. He just wants to crack a riddle about him and his father.

Audiences will respond to Bourne in this movie for the usual reasons. He outwits his antagonists with deadly swiftness and ingenuity while retaining our faith that he’s a man of good heart. It’s always fun to see a deluded CIA chief wear a damn-it’s-Bourne-again expression whenever he gets word of some unlikely getaway or takedown. Bourne’s derring-do has gotten so routinely outlandish that he might as well start tagging his handiwork, signing it “B” like Z for Zorro. Luckily, Damon still grounds the movie with his mastery of stoicism streaked by anguish. He’s magnetic as he outsmarts smarties and out-toughs toughs, then walks crisply away and blends into a crowd, with his baseball cap—this series’ highest form of camouflage—firmly in place. Otherwise, very little humor bubbles to the surface of this film: mostly, there’s Jones, who gets the film’s biggest laughs out of phrases as banal as “Let’s give it a shot.” Even for diehard series fans, the relentless pacing, the nonstop “tension music,” and the overused routines, like Bourne bludgeoning someone with the sudden opening of a door, or using his light fingers to pilfer a Molotov cocktail or an identity badge, could engender genre fatigue.

Greengrass, who made his name with Bloody Sunday (02), his reconstruction of British soldiers massacring Irish civil rights protesters in 1972, stages riot scenes as brilliantly as anyone since Gillo Pontecorvo (The Battle of Algiers). His docudrama approach here imbues the Athens riot with anarchic energy and danger, though it remains nothing more than a volatile backdrop to yet another motorcycle thrill ride through tight squeezes. Greengrass uses homemade incendiary weapons to punctuate the scene, but he can’t convince us that a rusty Bourne would meet Parsons in a public square filled with riot police and cameras without wearing a shred of disguise—not even a baseball cap. Still, that sequence is far more engaging than the climactic demolition derby run by Bourne and the Asset. A few effects are shocking and innovative, like a pilfered SWAT van slicing through traffic and sending smaller cars flying on either side, sometimes in pieces. It’s as over-the-top as The Blues Brothers, without the knockabout comedy. Greengrass and his editor and co-writer, Christopher Rouse, working closely with their favorite cinematographer, Barry Ackroyd, tuck in a tense homage to The Manchurian Candidate. But after a surprise turnaround during a shootout, audiences will say, “Saw that coming.” We can see a lot of this movie coming. What’s worse is what we don’t see: Greengrass and company tend to shoot hand-to-hand fighting so close to the bodies that it’s impossible to follow.

Cassel’s Asset achieves new peaks of malevolent, homicidal cool, a necessity to rouse rooting interest when our good guy creates so much collateral damage. But the freshest performer in the movie is Vikander, who electrifies Lee with charismatic intelligence and crackling elusiveness. She conjures passionate intensity when she’s working her keyboards, and her ability to convey racking anxiety without breaking character powers the Manchurian Candidate sequence. She elicits Greengrass’s most responsive work; in the movie’s best scenes, Lee’s quickness and dexterity turn computer displays into direct expressions of her shrewd intellect. An operations whiz scanning multiple screens while guiding actions thousands of miles away has rarely been performed and photographed with more confidence and éclat.

Nonetheless, we never feel the urgent involvement with Lee that we do with Helen Mirren’s military operations director in Gavin Hood’s Eye in the Sky, a low-profile film that has earned an ardent following since it opened four months ago. Hood’s lucid analysis of a drone strike has something better than a $120 million budget, and better than a beloved hero returning to action. Eye in the Sky has a powerhouse idea. That movie is like gourmet smart food. Jason Bourne is a popcorn movie.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.