Deep Focus: Ghostbusters

Let’s just get the silly controversy out of the way: the original Ghostbusters movies were not sacred works of art and revamping the franchise with women turns out to be the new film’s saving grace. The sisterhood at the center of Ghostbusters is stronger than a proton beam, more powerful than ectoplasm, and able to leap tall tales in a single bound. Performing with zest and originality, Melissa McCarthy as resilient true believer Abby Yates, Kristen Wiig as quick-thinking academic Erin Gilbert, Kate McKinnon as gleefully eccentric engineer Jillian Holtzmann, and Leslie Jones as the ultimate can-do New Yorker, MTA employee Patty Tolan, give you four good reasons to watch this more-hit-than-miss reboot. The sprawling, complex production ultimately swamps the talents of Paul Feig—a surprise since he directed last year’s globe-trotting McCarthy espionage comedy Spy with panache.

But that film’s script, which he wrote himself, was zingy and unpredictable. Here, the screenplay he co-wrote with Katie Dippold (who penned his execrable cop/buddy comedy The Heat) would feel as flimsy as an outline on an Etch A Sketch were it not for the improvisational wizards who fill it out with droll ad-libs, like Abby conjuring a vision of Patrick Swayze helping her throw a vase, and clever bits of business, like Erin starting to high-five Abby when she has a smoking hot weapon in her hand. McKinnon derives huge laughs from the inspired peculiarity of her facial expressions, just as Wiig does with her flaky inflections and deadpan, soft-spoken outrageousness. McCarthy continues to extend her range, pulling off a demonic-possession sequence with imaginative grace; she displays a startling knack for stylization when she assumes an eerily pleasant face. Jones puts all her comedic muscle behind slapping the devil out of her co-star, silencing naysayers who worried that she’d merely be playing sidekick to the certified brains in the outfit. After all, her Patty isn’t just street-smart: she’s New York subway-smart.

Give Feig credit for putting his key assets forward—the four stars, plus Chris Hemsworth as the male equivalent of a dumb-blonde receptionist. Feig knows that what makes them special is not simply that they’re upending stereotypes, but that they do it with their own sharp and sometimes warped humor. He gives the opening hour the shape of a classic origin story. Erin sets it in motion as she prepares to deliver her first lecture on physics in a big hall at Columbia. Dressed in an outfit so over-the-top proper that it’s almost sexy in reverse (a true Feig touch—he’s the rare contemporary director who dresses up for work), she shakes her tweedy booty in excitement at the prospect of filling lecture halls and gaining tenure. Then a stranger (Ed Begley Jr.) requests that she investigate a haunted Manhattan mansion. He has tracked her down via a book she wrote with her estranged girlhood friend Abby that now embarrasses her: Ghosts from Our Past: Both Literally and Figuratively: The Study of the Paranormal. Many lines that click in the film carry a knowing satiric touch like that “literally and figuratively.”

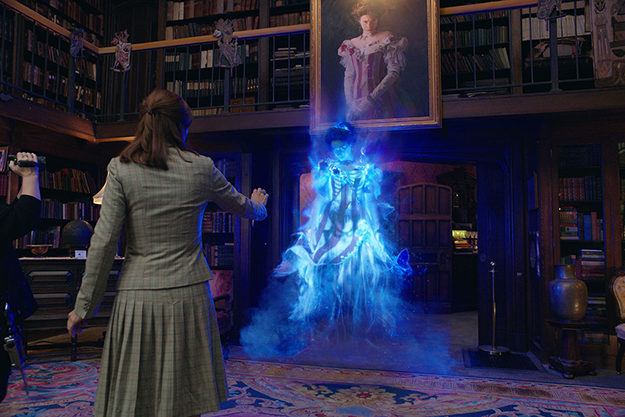

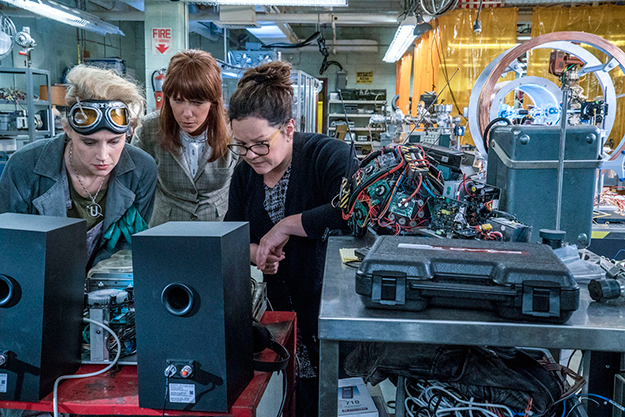

The irrepressible Abby has been selling the tome online to raise funds for the start-up research center she and Holtzmann, her new best bud, have quartered (temporarily, it turns out) on a disreputable campus. After Erin agrees to lead them to the ghostly estate in exchange for Abby removing the book from the Web, a new team of paranormal adventurers gets forged in green slime. Abby posts video of the trio pogoing while screaming, “Ghosts are real!” Once that gets out, Erin gets fired—and gets over it. How you gonna keep her up in Morningside Heights after she’s seen a ghost in the West Village? Thanks to Abby’s video, when Patty witnesses a ghastly electrical apparition that has nothing to do with a third rail, she knows who to call, even if they’re not yet known as Ghostbusters. And Patty realizes that she has something to bring to the party, too: not just that she reads a lot of New York City history but also that she can read people. Plus, she can finagle wheels from her uncle.

It’s blissfully easy for Feig’s company to revel in gender comedy without overplaying it. It’s perfect that the saga starts with Erin. She isn’t just a junior faculty member determined to hide a dodgy intellectual passion from her past. She’s a female physics PhD who came of age before STEM grants. A male peer wouldn’t worry so much about assembling a teaching costume or sweat about connecting to a white-haired eminence as white and as eminent as her department head (Charles Dance) with the necessary interest and deference. And the way Wiig plays her (brilliantly), Erin is the world’s worst poseur—each time she puts up a façade, it cracks before our eyes. Wiig makes Erin crisply analytic, even when she’s talking about intimate discomfort. I can think of no other actor who could have been so classy yet also so hilarious when reporting that slime has invaded her every nook and cranny. Every little thing Wiig does in Ghostbusters has an immediate kick and ticklish after-effect.

Feig has an eye and ear for idiosyncratic rhythms. The best parts of his direction are putting the stars together and then letting ’em rip, or, in some cases, not rip. When the team is dressed for action in their modified city-worker jumpsuits, and their paranormal gear is locked and loaded, Abby and Erin scream “Let’s Go!” almost simultaneously. Then they instantly defer to each other, out of sisterly consideration. Feig knows that comedy squads can be funnier when they’re not-so-well-oiled machines. What’s innately uproarious about McKinnon’s Holtzmann is that she’s deliriously happy to inhabit her own universe; that’s why she makes Wiig’s insecure Erin even more nervous. And Holtzmann’s goggle-like glasses ramp up rather than diffuse her insanely intense glare: you can feel McCarthy’s Abby feeding off her energy.

As he did in Spy, Feig expertly modulates McCarthy’s magnetism, and here he does the same for Jones. It’s euphoric to see them united with Wiig and McKinnon in erotic astonishment over landing Thor—that is, Chris Hemsworth—as their receptionist. Hemsworth relishes playing a doofus who carries around shirtless glossies and proposes a buxom ghost for their Web design. He delivers an equally jockish and jocular turn. But Hemsworth must bear the brunt of the climax’s decline from volatile ghost farce to incompetent spectacle. He’s positioned at the center of a giant musical-comedy number that stops dead in its tracks—literally and figuratively—and winds up mostly trapped behind the closing credits.

When the filmmaking machinery gears up for an apocalyptic crisis that resembles the not-so-grand finale of every other comic-book movie—as well as the original Ghostbusters—Feig loses control in the wheelhouse. In Spy he was able to build momentum and deliver a satisfying denouement, perhaps because even a glammed-up espionage movie is more grounded than a $144 million spooktacular. In Ghostbusters he does some careful preparation, but it all goes flooey. The first ghostbusting adventure is the best. The site (a Victorian brownstone turned museum), its history (an insane daughter who stabbed all the servants to death, then was locked up in the basement), and its supporting characters (including an unctuous tour guide who uses a trick candle to spook the customers) make for an apt combination of kookiness and classicism. While the hordes of subsequent ghosts are generic or cartoonish or too closely pegged to specific eras, the ghost in the museum carries a timeless, banshee-like aura; she’s hysterical in both senses of the word. Our hopes keep rising with a second sighting in a subway station and the recurring appearance of a creepy little fellow (Neil Casey) who calls his fellow subway riders “walking sewage” and warns Patty that “the Fourth Cataclysm” is coming.

Unfortunately, that’s three too many cataclysms to keep track of and it’s impossible to comprehend the mad logic of this fellow’s plan to detonate them. Feig lacks the cinematic necromancer’s eye for planting clues and motifs that resonate and grow in horror. All the audience can absorb is that (as Erin says) “someone is creating a device to amplify paranormal activity.” As Feig complicates the setpieces, they become increasingly erratic. Despite some merry passages, the spectral invasion at a heavy-metal concert registers more feebly as it goes along; it’s so feeble and dated that Ozzy Osbourne makes a guest appearance. What should have been a rousing climax dissipates into incoherence. Why does Times Square suddenly revert to the ’60s and ’70s, when you could still get a Nathan’s hot dog there or a buy a suit at Bond’s, the neon-draped “cathedral of clothing”? Ghostbusters posts a bigger logic deficit than most recent comic-book movies. Why don’t super-sized brawlers leave any lasting damage? Banged-up Gotham ends up looking slicker than before a chunk of it gets sucked into a vortex.

Still, the blinding, brain-smacking mayhem can’t wipe out the movie’s core of good feeling. Even after the action goes bust, the film’s gifted stars continue to radiate their own nuclear-powered, Amazonian brand of bonhomie.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.