Deep Focus: Finding Dory

Andrew Stanton’s follow-up to Finding Nemo (03) dares to be good—and that’s what makes it such great fun. Finding Dory doesn’t replay the same notes as the first film, and it doesn’t push for homey wisdom. By developing the logic behind the character of his beloved heroine, Dory (Ellen DeGeneres), a blue tang fish with short-term memory loss, Stanton arrives at a concoction that’s equally warm and witty. Watching it is the aesthetic equivalent of swimming in a heated pool set at just the right temperature. You feel exercised and soothed at the same time.

This is one case where a role written for a particular star is unimaginable without her. Stanton sensed that DeGeneres could go deeper with this character, and she does it without pushing her elastic humor out of shape. The premise is that Dory retains emotional memories even though she can’t recall the experiences that produced them. DeGeneres’s voice and Stanton’s animators generate a genial sort of friction by rubbing Dory’s bubbly surface against her growing undertow of sadness.

Too many family movies simply riff on The Wizard of Oz and restate versions of “There’s no place like home.” Finding Dory portrays a 21st-century extension of home as a long-distance network of kindred spirits. At the start, Dory lives contentedly on the Great Barrier Reef, just a few fins over from her friends, the widowed father clownfish Marlin (Albert Brooks) and his boy Nemo (Hayden Rolence). But her homing instincts get reactivated, first by a classroom discussion of seasonal migration, and then by the audiovisual spectacle of a robust school of migrating stingrays who belt out their migration song like a Russian men’s choir. She discovers that she has a mother and a father of her own, Jennie (Diane Keaton) and Charles (Eugene Levy). She sets out to find them. With the help of Marlin’s favorite mellow, high-speed sea turtle Crush (Stanton), the three friends zoom across the Pacific to “the Jewel of Morro Bay, California”—the Marine Life Institute where Dory’s family (she soon learns) set their crucial lesson to music: “Just keep swimming.” In one of the film’s many funny-savvy touches, she gets stuck in the plastic rings of a six-pack and winds up in the Institute’s quarantine while Marlin and Nemo swim free. (They soon infiltrate the Institute to find her.)

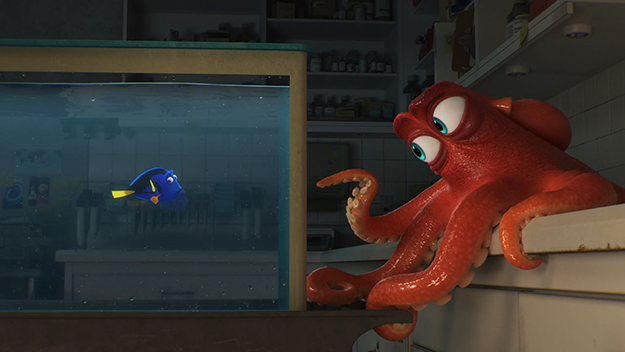

What ensues follows the contours of caper films and jailbreak movies but never feels like either one. It’s a movie without villains. The workers at the Institute dedicate themselves to the “rescue, rehabilitation, and release” of sick or injured fish and sea creatures. That includes Hank (Ed O’Neil), an octopus who lost a tentacle and became, as Dory says, a “septopus.” He’s also a mimic octopus, able to change shape and color so he can blend into the environment. (When we first meet him, he’s mimicking the cat in a “You Hang in There” poster.) One of the film’s many topsy-turvy jokes is that he doesn’t want to be set free—he’d prefer a glass case to the wild. He knows the Institute is sending a truck full of fish to the Greater Cleveland Aquarium. A score of blue tangs are scheduled for transport to Ohio—and Dory has been tagged to be one of them.

The Institute’s official voice, Sigourney Weaver playing “Sigourney Weaver,” is a model of brisk humanity. She makes the Institute’s recorded mission statement sound so energetic and inspirational that Dory soon refers to her as a personal friend. (It may be the most hilarious use of a movie star’s name since Peter Cook’s devil in Bedazzled pronounced the magic words, “Julie Andrews!”) Dory rediscovers her history the way actors feel their way into a part. She retrieves the sense memory that she was happy at the MLI and reconnects with a near-sighted whale shark named Destiny (Kaitlin Olson), who had been her “pipe pal” when they were kids, communicating through the plumbing. The film is as high-spirited and freewheeling about unlikely buddies as it is about their defects and injuries, like Hank’s missing tentacle, Destiny’s myopia (she’s always knocking into walls), and even the likely concussion of a beluga whale named Bailey (Ty Burrell), who almost convinces himself that a conk on his bulbous head has ruined his biological sonar or “echo-location” (referred to in the film as “The World’s Most Powerful Pair of Glasses”). Stanton pulls off free-swinging comic strokes, whether from crabs scurrying for cover—we realize that they’re hermit crabs—or a couple of sea lions acting super-territorial (played by Wire co-stars Idris Elba and Dominic West) or a startlingly bold parody of fish-eating-fish posters. The funniest moments are the most cheerful, too, as when little fish and big fish meet in peace because they’re all FODs (friends of Dory’s).

Stanton is a born comic-fantasy director. In a Stanton movie like this one or Wall-E or Finding Nemo (and, for my money, the unjustly maligned live-action fantasy John Carter), you can’t separate the lush diversity of the images from the director’s infinite playfulness and heartfelt inventions. (Angus MacLane co-directed Finding Dory; Bob Peterson and Victoria Strouse collaborated with Stanton on the original story.) Even a seemingly simple scene such as Dory balking before “going through the pipes” to find her parents—she’s afraid she won’t be able to follow the directions, “two lefts, straight, and you’ll hit it”—contains rapid-fire miracles of expressive staging and editing. Stanton contrasts Dory’s size with that of Destiny, the whale shark, as this largest fish in the sea (and the Institute) tries to nudge the tiny blue tang toward a pipe. At the scene’s mid-point, Hank drapes himself on top of the pipe’s opening like a fearsome decorative door-knocker, while Dory nervously sails into the pipe and out again. Then Hank and Dory swim into a two-shot: he lunges a scary tentacle at her and bellows “tag”—meaning the tag she wears that could secure him a seat on the truck to Cleveland.

The movie is full of subjective perspectives, most dramatically when Dory has her epiphany of “home” and zooms through the Great Barrier Reef, reducing it to a carnival blur, and, later, when Stanton depicts Bailey’s echo-location as X-ray vision. He includes audio jokes that also double as existential clues, whether it’s the omnipresent presence of “Sigourney Weaver” or Dory “speaking whale,” which she apparently thinks means talking with a loud voice, low register, glacial pace and nonsensical diction. Stanton conjures unselfconscious metaphors. When Marlon and Nemo try to surf jet streams of water that shoot up from a plaza—as they strive to get from a gift shop tank to a tidal pool exhibit—you don’t have time to think “fish out of water,” not even when they flop onto the concrete.

Finding Dory isn’t as beautifully sustained as Finding Nemo or Wall-E, and it does feel over-long. After all, balancing the richness and detail of a thoroughly re-imagined world with an illusion of spontaneity is an almost impossible task. But Stanton does exactly that with the film’s final one-two punch: a pair of climaxes so emotionally complete that neither one is “anti-.” The first pays tribute to the devotion and foresight of Dory’s parents, who have never stopped preparing for Dory’s return. Without giving too much away, let’s just say that they create a circle of life with shells. The second is a brilliant slapstick sequence with an extraordinarily clever buildup—otters make adorable decoys—and the zestiest comic car chase in years. It’s whimsical and inspired. Hank the septopus takes the wheel of the truck headed to Cleveland’s aquarium, and fish fly from one open tank to another in the back as he maneuvers hairpin turns. The fish chant “RELEASE! RELEASE! RELEASE!” just as the crowds screamed “ATTICA!” in Dog Day Afternoon.

“What is so great about plans?” Dory asks Hank. A few beats later she adds: “The best things happen by chance, because that’s life.” Actually, some of the best things in this movie happen because of her parents’ best-laid plans. As Fitzgerald famously said: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” That’s the test of a first-rate comedy mind, too, and Stanton just about aces it here.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.