Deep Focus: De Palma

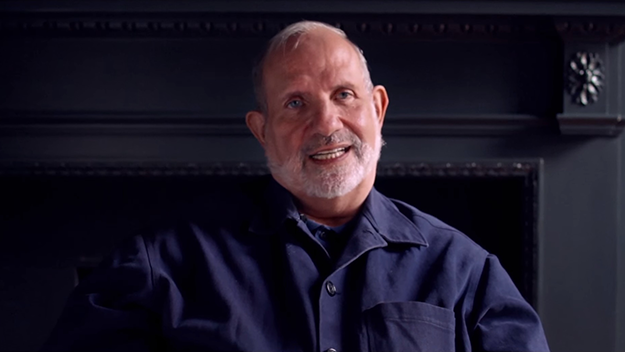

De Palma is to director profiles what Brian De Palma films are to conventional thrillers: its brilliance, humor, and humanity put it leagues beyond the usual “making-of” doc or DVD extra. Rarely has a filmmaker so energetically and eloquently revealed the pressures and pleasures of a director’s work. Yet De Palma’s co-directors, Noah Baumbach (When We’re Young, Mistress America) and Jake Paltrow (Young Ones) deserve credit for making all the right moves—and making them seem like no moves at all. The film is 111 minutes—taken from 30-40 hours—of De Palma talking to them while they remain offscreen. The framing of their subject from the shoulders up, the ultra-clean sound recording that allows him to be 100 percent conversational, and their soft touch at inserting illustrative clips and photos combines with De Palma’s vibrant storytelling to form an indelible bond with each viewer. Baumbach and Paltrow are friends with De Palma, yet rather than show off their personal connection, they attempt to share their intimacy with the audience. They succeed. The one time De Palma addresses them as “you guys,” it may take you a minute to realize that he’s talking to them, not you and your date.

From the beginning, their documentary rescues Brian De Palma from the misunderstandings of critics both positive and negative. No director ever had a more inspired or perceptive champion than De Palma did in Pauline Kael, yet she once lumped him together with Scorsese, Coppola, and Altman as Catholic directors who ”have grown up with a sense of sin and a deep-seated feeling that things aren’t going to get much better in this life. They’re not uplifters or reformers, like some of the Protestant directors of an earlier era, or muckraking idealists, like some of the earlier Jewish directors . . . .[Their work] combines elements of ritual and poetry in their heightened realism.” She gets at the new sensibility these breakout filmmakers shared, but Catholicism doesn’t seem to figure much in De Palma’s temperament or upbringing. He attended Friends’ Central School in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, a renowned Quaker institution whose other notable alumni include poet Hilda Doolittle (aka “H.D.”) and architect and city planner Edmund Bacon (Kevin’s father). De Palma’s bloody imagery stemmed mostly from witnessing his orthopedic surgeon father perform operations, and his pervasive sense of sin appears to have come from his knowledge that his dad was cheating on his mom. De Palma confides that his parents’ unhappy marriage poisoned his home; he recalls tracking down his father’s lover, knife in hand, and finding her hiding in a closet.

Baumbach and Paltrow also rescue their friend from the trend-watchers who always grouped De Palma with Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and company as “The Movie Brats.” He and Martin Scorsese had more hipster éclat and street smarts than the rest of those guys. What is clear from the start of De Palma is his saturnine shrewdness and intelligence, his witty and original personality, his canny survival instinct, and his determination to grow as an artist. The movie doesn’t dwell on De Palma’s life outside of movies, but it does touch on his youth as an adolescent science fair winner with an eye for the young ladies. De Palma proves to be a droll raconteur, especially when he tells self-deprecating stories. Once, for example, he answered a dare to record the girls’ sex-education class, and got turned in by the girl who dared him.

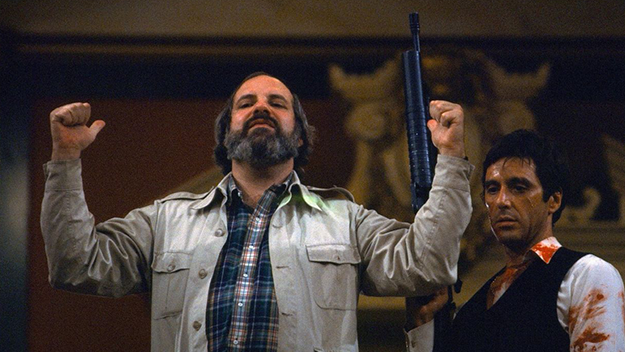

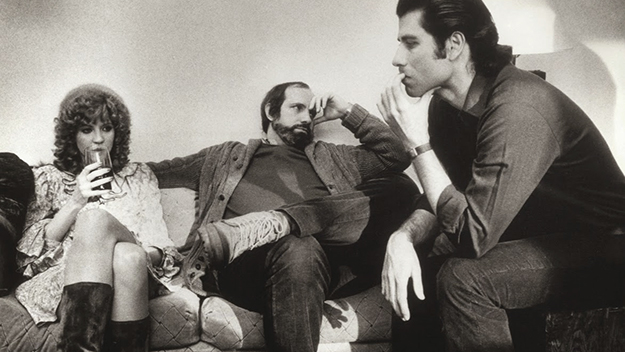

Movie Brat haters will be surprised to learn that he entered Columbia to study physics, math, and Russian, but he soon began haunting New York’s celluloid oases, like Amos Vogel’s subscription series, Cinema 16, which showcased his early short, Woton’s Wake (62). Doing graduate work in theater arts at Sarah Lawrence, he co-directed The Wedding Party (made in ’63, released in ’69) with his mentor Wilford Leach and classmate Cynthia Munroe, then realized that he knew more about movie directing than his stage-oriented teacher (Leach later won two Tonys). De Palma’s own experience in theater and acting classes informs his knack for casting: Wedding Party was the first film for Robert De Niro as well as for Sarah Lawrence acting students like Jill Clayburgh and Jennifer Salt. (Clayburgh would marry De Palma’s future collaborator, playwright David Rabe, and Salt would, for a while, be part of De Palma’s stock company.) De Palma would shape Sissy Spacek’s and Piper Laurie’s astonishing performances in Carrie as well as standout work from John Travolta (Blow Out), Michael J. Fox (Casualties of War), Al Pacino and Sean Penn (Carlito’s Way), and Sean Connery (The Untouchables). In De Palma, when he depicts the outbursts of prized colleagues like composer Bernard Herrmann, cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, and Pacino, he’s a first-class comic actor himself.

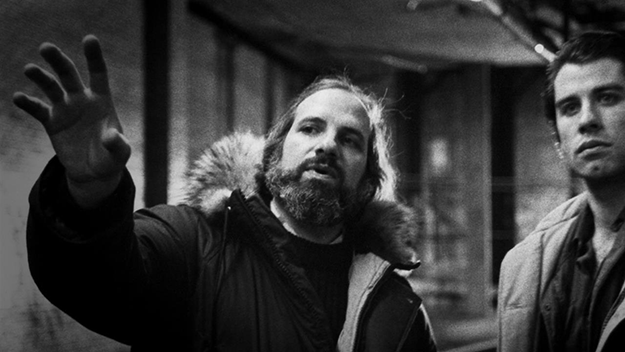

The way Baumbach and Paltrow frame his story, De Palma comes on in his early days like a one-man New York New Wave. Through most of the 1960s, De Palma earned his daily bread doing documentaries, including the performance-art film Dionysus in ’69, in which he used split screen to capture the charged interaction of the audience and the actors. He first drew critical attention with his controversial “underground” comedies Greetings (68) and Hi, Mom! (70), a grungy tour de force with the now legendary satirical theater piece called “Be Black, Baby.” He made what should have been a pop-rock milestone in his burlesque musical horror film, Phantom of the Paradise (74), but he didn’t win broad acclaim and box-office success until the black-comic teen-angst horror movie Carrie (76). Not even Carrie, though, gave him the sustained liftoff that Spielberg got with Jaws. De Palma’s career has always zigged and zagged between “smart” professional moves designed to keep him in the game and expressions of personal obsession.

Supporters like Kael noted that in both cases he kept perfecting his craft, broadening his subject matter, and seizing opportunities for innovation. But only rarely would he hit the critical-popular sweet spot with films like Dressed to Kill (80), and even then he faced waves of accusations that he was exploiting women and vulgarizing Hitchcock. Tragically, his out-and-out masterpieces, Blow Out (81) and Casualties of War (89), divided critics and failed to win over a mass audience. (As Rolling Stone’s film critic in the early 1980s, I wrote a rave for Blow Out.)

Happily, Baumbach and Paltrow’s quick-fingered succession of excerpts and the director’s running commentary explode conventional wisdom while conveying both his virtuosity and indelible engagement with his times. You can’t see this sampling without savoring how issues like race, political executions, and urban crime recur explicitly and implicitly in his work. Although De Palma’s movies may seem, at first glance, “dated,” they turn out to be enveloping and immediate—time capsules that go off like fireworks. Supreme entertainments like Carrie and Dressed to Kill contain unexpected resonances. Who would have guessed that in Carrie, Laurie’s remarkable paradox of a performance—her passionate portrayal of a repressed and repressive religious zealot—would reverberate even more strongly in 2016 than it did in 1976? De Palma contains the clip of Carrie using telekinesis to kill her mom with her own cooking utensils, leaving the madwoman looking like a distaff St. Sebastian. (Decades later, Laurie still marveled to me at De Palma’s ingenuity at pulling off that stunt via wires attached to the blades and her body.)

The director lucidly recounts the challenges of that movie, including setting young girls at ease with their nudity (luckily, Spacek set a good example) and executing long, looping camera moves on prom night. It’s refreshing that he’s so frank, here and throughout, about his mistakes, such as using split-screen during Carrie’s climactic carnage. He learned, he says, that split-screen is ineffective for action scenes: even in the finished film, it clutters rather than clarifies the action. What’s more gratifying is the way his vibrant patter melds with his seductive compositions. His words and images instantly express how exultantly and beautifully he stylized Stephen King’s novel, infusing it with his feeling for the giddiness of youth. He choreographed the teenage bodies moving through a locker room filled with steam like a languorous comic ballet.

Carrie turned out to be a startlingly personal movie, especially considering that De Palma didn’t initiate the project. In the documentary, when you see the various blades piercing into Laurie’s body, you’ve got to think of little Brian watching his dad slicing through tissue in the OR. Dressed to Kill, which he did write as well as direct, is almost autobiographical. De Palma, the Philadelphia technology freak who tried to protect his mother from his dad’s philandering, is embodied by the young Keith Gordon, playing a Manhattan technology freak trying to discover who fatally cut his mother in an elevator. In De Palma, we learn that a movie so often interpreted as a Hitchcock pastiche actually derived from De Palma’s attempt to film Gerald Walker’s Cruising (before William Friedkin got to it), his college reverie of picking up women in an art gallery, and a lucky bit of channel-flipping that brought him to a talk show on transsexuals. Dressed to Kill is not just a slasher film executed with straight-razor precision. It’s soaked in the psychological fantasies of its doomed heroine (Angie Dickinson) as well as the grittier realities of the hero’s hooker helper (Nancy Allen). The older woman’s steamy opening dream/nightmare melds with her heated imaginings about the stylish man she attracts in the museum. (Allen and De Palma married in 1979 and divorced in 1984. De Palma mentions this marriage and his other two in passing, mostly in connection to his work.)

De Palma creates a visual style so operatic and balletic that Dressed to Kill boasts the imaginative impact of surrealism, while remaining cunningly observant about life in New York circa 1980. What makes De Palma a master pop satirist is his refusal to preach and his utter lack of inhibition. When Allen runs into the subway to escape the killer, it’s a great out-of-the-frying-pan-into-the-fire moment. Who would seek safety in the New York subways of the Mayor Koch era? De Palma captures the racial and social-political tensions of that moment without dilution or apology.

In De Palma, the director talks perceptively about his own influences. The documentary opens with De Palma’s memories of seeing Vertigo as a kid and coming to appreciate it as an adult. He says filmmakers love Hitchcock’s movie because it’s all about what directors do: Hitchcock creates a romantic illusion—and then kills it, twice. In the clips from the Master of Suspense, you can see everything De Palma learned from Hitchcock: his cunning use of subjective camera and his deployment of every tool at a director’s disposal, including blocking, lighting, cutting, and special effects to adopt his characters’ often dizzying perspectives. Hitchcock, though, rarely moved his camera as sinuously as De Palma, who drew on the work of many other directors, including Orson Welles and Stanley Kubrick, to create his own simultaneously voluptuous and incisive style. De Palma never sounds more Hitchcockian in De Palma than when he says he starts with “a construction,” not characters, then engages the actors to fill them in and root them in reality—unlike, he says, “you guys” (Baumbach and Paltrow), who start with characters and build films around them. It’s remarkably similar to what Truffaut told Hitchcock: “Your point of departure is not the content but the container.” This stance explains perfectly why he would clash with a character-is-action filmmaker of equal stature, Robert Towne, on the screenplay for Mission Impossible.

This film definitively illustrates that with De Palma, as with any talented movie artist, the truth about his work is often richer and more elusive than his statement of intent. Blow Out stems from a plot De Palma sees as “a construction”: a movie sound technician (Travolta) uses the tools of his trade to prove that a governor’s fatal car accident was a political execution. Every scrap of that construction seems personal to De Palma and becomes a matter of life or death to us. It kicks off with a parody of soft-core horror porn but ends with a portrait of a man trapped inside his own technology. Blow Out is such a mind-blowing movie because it does the reverse of what De Palma says Hitchcock does in Vertigo. De Palma and his hero don’t spend the movie creating an illusion but uncovering a reality moviegoers recognize as a mash-up—not of movie thrillers, but of all the Kennedy tragedies, Chappaquiddick, as well as the assassinations. The central relationship is not an obsessive romance but a tender friendship between the soundman and a makeup counter girl and escort (Nancy Allen) who is sitting next to Pennsylvania’s governor when a tire blows out and his car goes into the Schuylkill River. When Travolta’s character turns the death throes of a murdered woman into the “good scream” he’s been seeking for an exploitation picture, the soundtrack for the movie-within-the-movie becomes the hero’s continuous loop of suffering. De Palma describes the underlying sting of Blow Out: its subliminal message is that even if we stumbled upon exactly what happened in the JFK assassination, nobody would care.

De Palma is unabashedly emotional and moving when he admits that Travolta’s way of muttering “It’s a good scream…good scream” at the end of Blow Out gets him every time. Everything that’s fecund and vital about De Palma’s subsequent 35 years of moviemaking flows from the complex legacy of Blow Out. Of course that includes the searingly naturalistic Casualties of War, Blow Out’s opposite twin. Here he renders a forgotten real-life story about a Vietnam War atrocity—battle-scarred U.S. soldiers raping and murdering an innocent Vietnamese girl—with so much empathy and artistry that it would wring tears from xenophobes if you could only get them into the theater.

He’ll also be remembered for his two unexpected pop-culture phenomena, Scarface (83) and The Untouchables (87). I vastly prefer his superb tragic gangster film Carlito’s Way (93), parts of his tricky assassination thriller Snake Eyes (98), his sexy, playful, perfect dream thriller Femme Fatale (02), and Redacted (07). This brutal, chastening companion piece to Casualties of War, which fictionalizes a similar atrocity from the Iraq War, renders it in a cutting-edge collage of fly-on-the-wall digital footage and simulated streaming video from American and insurgent Internet sites. In that movie, De Palma, with the intuition of a born filmmaker, connects our inadequate response to public tragedy to the onslaught of new media.

All of De Palma’s movies contain patches of sublimity or inventiveness, including the much-maligned Mission to Mars (00) and The Black Dahlia (06). De Palma provides a one-of-a-kind filmmaker’s perspective on everything from the runaway costs and escalating burdens of big-studio moviemaking—he made Carrie for $1.8 million, Mission to Mars for $100 million—to the haphazard ways an American movie artist-entertainer must cobble together a career from mixed opportunities and accidents. At age 75, he ruefully admits that filmmakers are usually remembered for movies they make in their 30s, 40s, and 50s. He talks straight from the shoulder about his cave-in to commercial worries on the epochal calamity of The Bonfire of the Vanities (90), and about his inability to find a satisfying ending to Snake Eyes. He tells Baumbach and Paltrow that endings are always a problem, and that you’re lucky if you find two or three that hit the bull’s-eye in the course of a career.

De Palma has the best kind of ending for a director documentary: it leaves us wondering what’s yet to come from this protean and multifaceted filmmaker.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.