Deep Focus: Creed

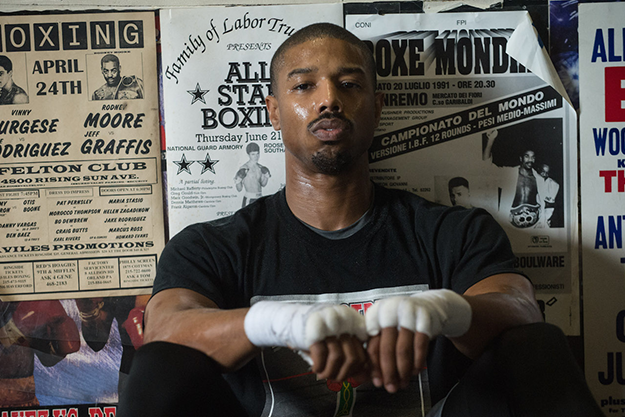

At the time of Rocky II (79) I had a dream: I wished that Sylvester Stallone had made Apollo I instead. Thirty-six years and four more sequels later, that dream comes true with Ryan Coogler’s reboot, Creed. Apollo Creed died in the ring fighting a Russian behemoth in Rocky IV, but his presence permeates this buoyant and joyous if at times bombastic movie about the sudden rise of his illegitimate son, Adonis Johnson (Michael B. Jordan).

Creed is every inch a Rocky movie. Yet somehow, Coogler and his co-writer, Aaron Covington, turn the story of two royal boxing families—the Creeds and the Balboas—into an underdog fable without causing you to wince. The top dog is the light-heavyweight champ from working-class Liverpool, “Pretty Ricky” Conlan (Tony Bellew), who is, pound for pound, the world’s number-one fighter. He takes his supremacy for granted, not realizing that Creed’s kid has been through his own school of hard knocks.

Adonis’s mother had an affair with Apollo and kept her son’s parentage a secret. After she died, he drifted in and out of foster care and juvenile detention centers in Los Angeles until Apollo’s widow, Mary Anne (Phylicia Rashad), sought him out and saved him. Blessed (or cursed) with fists of fury even as a boy—a youth worker describes him as a good kid, when he isn’t fighting—Adonis’s neediness and anger prevent him from settling into a lucrative desk job in young manhood. He tries to slake his thirst for fighting in weekend matches down Tijuana way, but he can’t get no satisfaction. He convinces himself that the only man who can give him the technique and seasoning he needs to be his best is his dad’s worthiest combatant and best friend, Rocky Balboa.

The epitome of a Philadelphia lifer, Rocky is content to run his neighborhood restaurant, Adrian’s, and to share the day’s news with Adrian and his best friend Paulie at their graves. Still, when Adonis begs for him to be his trainer/manager, he finds he can’t say no. The boy’s artless ardor gets to him; so does a sense of obligation.

What makes the movie so refreshingly entertaining and unpredictably moving is that Coogler takes the series’ rah-rah, go-for-it clichés as his given—or what Henry James would call, his donnée—and invests them with genuine feeling and individuality. Working in a broad-stroke genre enables this 29-year-old writer-director to tear into charged emotional subjects without hemming and hawing. It might be dramatically convenient for Adonis to discover that his downstairs neighbor at his Philly apartment is a gorgeous aspiring singer, Bianca (Tessa Thompson). Their callings clash, at first comically (she composes and rehearses too loud for him to sleep) and later wrenchingly (he takes out his frustrations on an influential rock-club headliner). Thompson’s smartness and tenderness and Jordan’s raw honesty and ardor set the romantic stakes very high.

Coogler proved he can be a master realist with his astonishing debut feature, Fruitvale Station (13), which dramatized the final hours of Oscar Grant before a transit cop shot him on New Year’s Day, 2009. He’s also got a diviner’s sense for deriving palpable drama from what remains unseen—beyond the frame or in the characters’ heads. Creed’s sneak-attack power pivots on the invisible presence of Apollo Creed, which is as it should be. Rocky Balboa may have become America’s iconic come-from-behind winner, but for my money, Apollo Creed was the greater character—not just a Muhammad Ali spin-off, but, as embodied by Carl Weathers, an Ali with a generous spirit who would give his fiercest contender another shot at the crown simply to prove he is the greatest, but would never rag on Rocky the way Ali did on another Philly immortal, Joe Frazier.

Adonis must reconcile the knowledge that his dad was a great boxer and a great guy with his own feelings of abandonment. Jordan captures, beautifully, the young man’s roiling undercurrents of anger and longing for Apollo. In a masterstroke, when Adonis studies his father’s most famous fights on YouTube, he puts himself in Rocky’s place, not Apollo’s, and lands one haymaker after another on his dad’s jaw. An hour and a half later, Adonis confesses to Rocky that his goal in life is to prove that he wasn’t “a mistake.” Rather than any of the pounding ring action, the intimate admission gives this boisterous film its knockout moment.

Rocky has his own scores to settle. Adonis reminds him that he gave a fine oration at Apollo’s funeral, but he hasn’t contacted his widow since then. The younger man scores a clean hit. The movie is both a dramatic exploration and a creative example of the need to build on the past rather than indulge in nostalgia. When Adonis pushes Rocky into investing time, heart, and sweat into his future, everybody wins—especially, and surprisingly, Stallone.

He hasn’t been this engaging since he wrote and starred in Rocky (76), in which he refreshed the concept of a loser making good, by never viewing Rocky as a loser. Even when everyone else saw the fighter as a stumblebum, audiences knew that he deserved to win—or at least “to go the distance.” He displayed unconventional wit and sensitivity whether he was playing with his pet turtles, “Cuff” and “Link,” or courting his pet-store worker lover Adrian. What made the Rocky sequels feel so cheap (apart from the hollow hype of the filmmaking) was their soulless repetition: everything that was charming hardened into cuteness. Stallone was so wedded to his own comeback-kid formula that Rocky had to learn the same old lessons about focus, self-actualization, and trusting kith and kin, over and over again.

What gave Rocky Balboa (06) its vitality was Stallone’s seriocomic recognition that his alter ego had long been spinning his wheels. Stallone was equally marvelous as the kind of aging athlete who rolls out the same old sports stories to regale his fans and the kind of aging widower whose daily ritual stop at his wife’s gravesite is a kind of death-in-life-line. He deepens that characterization in Creed. It’s much funnier and richer because Adonis forces Rocky to go beyond his comfort zone and share his wisdom, which is, wittily and wonderfully, the opposite of abstract Zen mastery. Rocky and his training tricks are rooted in the Philly earth, whether he’s improving Adonis’s speed by forcing him to catch chickens or compelling him to do his roadwork on city streets. In one of Coogler’s stirring contemporary touches, Adonis attracts an entourage of bikers who, like Baltimore’s 12 O’Clock Boys, ride vertically, or “straight back,” so their profile resembles the hands of a clock at noon or midnight. Coogler’s establishment of a vital, eclectic atmosphere helps keep the wily old vet and his fiery young star perfectly in tune.

Some of the movie’s most memorable images are Stallone and Jordan facing each other in a workout and swaying in synch, from the waist up; some of its most memorable sounds are Stallone’s mellow tones as Rocky tells Adonis that he’s still watching him and training him though others might be teaching him specific skills. Stallone has never been more powerful and graceful than he is here, at his most laid back. His casualness takes the edge off cornball jokes, like the one about the chickens getting slower; his bowed posture and deep-seated expressions are like gravity-defying sculptures. But even when the movie dips into tear-jerking, Stallone doesn’t give into sentimentality.

Even when Creed threatens to fall into show-off virtuosity, Coogler mostly keeps his balance. As befits the material, from the very first shots of a white corridor with a red stripe filling with green-shirted boys at a detention center, Coogler goes for a sharper theatrical edge than he did in Fruitvale Station. At his best, his new film is both visually striking and expressive: those lightning opening vignettes, for example, convey the volatile, claustrophobic tensions of juvie in mere seconds. At his worst, he falls into the overblown rhetoric of most Rocky movies, especially in the climactic fight, which alternates corner-man wisdom and bludgeoning blows.

The movie ends with a lovely coda. When Coogler’s mojo is in top gear, he pulls you into the action psychologically and viscerally. He choreographs Adonis’s first mature fight into a single two-minute shot: after the camera swerves to take in Rocky’s imprecations, it immediately swings back to show their impact on Adonis. At moments like that, Coogler is the cinematic equivalent of a 12 O’Clock Boy—his precocity takes your breath away.