Deep Focus: Come and See

Come and See (Elem Klimov, 1985)

The restoration of Come and See (1985), Elem Klimov’s unblinking depiction of Nazi armies wreaking carnage on Soviet Belorussia in 1943, enables us to view this disturbing, mesmerizing epic with fresh eyes as it turns Klimov’s lens into a burning glass. Originally called Kill Hitler, this film ranks with Kon Ichikawa’s Fires on the Plain as a World War II nightmare of humanity pushed beyond its limits. It rivals Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal as an apocalyptic vision of mortal fear and mass sadism flaying every vestige of faith, hope, and charity in a scarred quarter of the world.

The title comes, like Bergman’s, from the Book of Revelation: when the Lamb of God opens the fourth seal of the scroll of revelation, John hears “the voice of the fourth beast say, Come and see. And I looked, and behold a pale horse; and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him.” In Soviet Belorussia’s seemingly impenetrable forests and vast bewildering plains, Klimov creates a fertile landscape for Death. He locates Hell in the soul-shriveling anger and despair that settle in its teenage survivor’s face over the course of a depravity-packed few days. The hero’s circular travels bring him back to where he started, and Klimov, with a string of stinging closeups, delivers an existential twist on classic odysseys.

Aleksei Kravchenko, 14 at the start of production, plays Flyora, a green recruit to a ragtag bunch of rural Soviet partisans. Flyora enters the film a juvenile patriot, eager for the fight. He nearly gets crushed in the collapse of civic and military order as Nazi death squads scorch the earth. Suffering, not combat, defines Flyora as a person and a soldier. He’s essentially on his own for half the movie. Separated from his unit, Flyora witnesses and endures a secession of atrocities completely different from conventional skirmishes or guerrilla attacks. He ricochets from one crisis to another as enemy planes patrol the sky and German forces wage “total war” across the countryside, annihilating whole villages and populations. He learns that there’s no limit to the punishment occupiers can exact from people they consider Other.

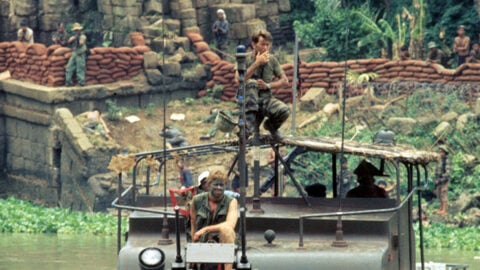

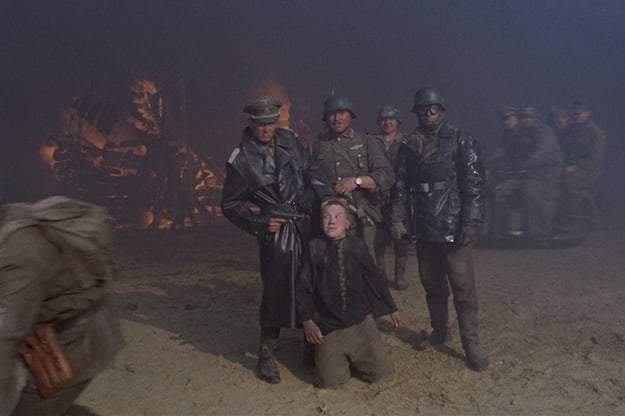

When the partisans surround a clutch of German war criminals who have burned entire communities alive, the key question becomes: will the Soviets torture them or summon an ounce of mercy? Come and See compels an audience to evaluate its characters’ morality according to what they won’t do.

Janus Films’ press notes state that Klimov tried to hypnotize Kravchenko during the most devastating sequences, “so he wouldn’t remember them.” Klimov didn’t succeed, but Kravchenko does: he hypnotizes us. He possesses the magnetism of a born performer and the emotional transparency of a great one. (It’s comforting to learn that he has worked steadily in theater, film, and television throughout his adulthood; he appears in the forthcoming film adaptation of another demonic wartime pilgrimage, Jerzy Kosiński’s The Painted Bird.) Kravchenko takes Flyora from giddy boyhood and ravaged youth to wary premature adult. Only at the end of Come and See can we appreciate his range. For the previous 142 minutes, we’re too viscerally caught up in Flyora’s angst to assess Kravchenko’s artistry. Kravchenko’s expressive features invite us into his head and into his soul. We know exactly when he’s wondering, “What has become of this world? What has become of me?”

Klimov uses sound and image to frame the movie in unorthodox ways, drawing us ever deeper into Flyora’s harrowing coming of age—or, rather, his leapfrog over adolescence. The innovative sound design filters the audio partly through Flyora’s damaged ears and psyche—we experience his industrial-strength tinnitus after a bombing raid—and partly through the director’s sensibility—we faintly hear a Strauss waltz as Flyora barely keeps his footing in a swamp. The soundtrack achieves a crackling, nerve-shattering realism during the razing of a village, only to stabilize for a climactic epiphany. Klimov and his cinematographer, Aleksei Rodionov, employ Steadicam not for smooth, mesmerizing effects but to trace jagged arcs in the irrational movements of panicked Belorussians and of Nazis staging genocide. The moviemakers’ visual scheme has been called “subjective”—linked to Flyora’s perspective, only—but it actually assumes his point of view and other characters’ in turn. Often, what Flyora doesn’t see is what hurts him.

Beyond these virtuoso techniques, Klimov’s dramatic vitality, his control of shifting tones, and his mastery of surprise are what galvanize Come and See. Terrifying as this movie is, we always want to know what happens next—partly because we hope what happens next will explain what happened before.

Klimov’s boyhood memories of the Battle of Stalingrad and his evacuation from the city informed this audacious film. Co-writer Ales Adamovich drew directly on his teen experiences in a Soviet Belorussian partisan unit in 1942 and ’43. Adamovich was already a culture hero for his fact-based novel The Khatyn Story, a 1972 rendering of a village massacre and conflagration, which also featured a protagonist named Flyora, and he became a pioneer of documentary journalism with his 1975 epic about the Nazi slaughter of Belorussian villagers, Out of the Fire (co-written with Yanka Bryl and Vladimir Kolesnik). Adamovich’s fusion of oral history and sweeping chronicle heavily influenced the work of Svetlana Alexievich, who won the Nobel Prize in 2015 and in 1985 published Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II, based largely on the accounts of boys and girls from this same area. (An English translation appeared just last year.) Klimov’s wife, the gifted Larisa Shepitko, was preparing her own jaw-dropping World War II film, The Ascent (1976), based on a novel by Belorussian writer Vasil Bykov, when Klimov and Adamovich were trying to launch Come and See.

The movie starts in the realm of absurdist farce, evolves into absurdist nightmare, and finally lands in an out-and-out apocalypse. In the beginning, a village elder warns two unseen boys against digging up weapons from the sands where partisans have buried them. (We eventually understand that he’s worried about the SS observing these young smart alecks.) A surly towhead appears out of nowhere, dressed like he’s ready for tank war in North Africa, mimicking the codger as if he were a Nazi drill sergeant. When the unruly lad walks into a head shot, we see he’s talking to Flyora, crouching hidden in the shrubbery. The credits roll as these buddies saunter down a hill toward drift-filled trenches containing Soviet rifles. Flyora needs a gun to become the resistance fighter of his dreams.

This introduction is as jarring and absurdist as a Beckett or Ionesco opening, only real. The boys duck and cover when a German plane hovers overhead. Would the pilot actually home in on targets as slight as these boys? (Yes.) In a deliberately jagged succession of shots, Klimov depicts actions that don’t make immediate sense—like Flyora lying face down in a trench, his body clenching and trembling as he pulls with all his might to extract the rifle beneath him. The director creates a scary sort of intrigue: How are we to take these opaque or incongruous activities? Soon Klimov ushers us inside Flyora’s home, as the lad sits, rifle by his side, and smiles stupidly at his distraught mother. We realize we’re in a region teetering on catastrophic breakdown, inside and out. Klimov juxtaposes tight shots of the anguished mom with Flyora’s idiot grin. She wields an axe and asks him to kill her and his kid twin sisters, too, considering how helpless they will be if Flyora goes away. After he and his mom wrestle over the axe, Flyora gestures comically to the girls, making them think it’s all play.

The game gets even more frightening when two partisan mobilizers, one sporting a discarded German helmet and gorget, aim to mislead any spying Nazi eyes by pretending to force Flyora to go with them. They bruise his face, dump him in a cart with an anonymous, German-speaking man, and rattle deep into the forest. Klimov’s disconcerting art combines mystery and charged confrontations: he thrusts us into action that unfolds at fever pitch and compels us to get our bearings along with Flyora. The director intensifies our connection with the awkward teen as he stumbles through a makeshift partisan camp where discipline is erratic and the guest of honor is a cow bound for slaughter.

Klimov and Adamovich’s script delivers a structured vision of chaos without losing the sense of anarchy that makes the finished movie feel so true. It’s comparable to Bergman’s searing exploration of an unnamed 20th-century civil war in Shame (1968). Mad details resonate without any literal explanation. A goofy cameraman sports a Hitler/Chaplin moustache when assembling troops for a group photo, then removes it as he jumps into the picture. Flyora performs menial jobs like scrubbing a cauldron from the inside. He can’t tell whether a pretty sometime nurse named Glasha (Olga Mironova) mocks him as she strews flowers on his semi-naked body in the giant pot. Flyora intends to demonstrate his courage. So he weeps when his commander, Kosach (Liubomiras Laucevičius), orders him to swap his fine boots for a veteran’s deteriorating ones: the practiced soldier must be outfitted to fight while Flyora stands back and plays sentry in the woods. Flyora’s outsize humiliation melds with the loony poignancy of Glasha, who loves Kosach and fears he’ll be slain by the Nazis. A bombing and paratrooper raid on Kosach’s camp leaves an enemy hanging from nearby limbs and sends Flyora and Glasha fleeing to his village, where the scope of Nazi barbarism comes into scabrous focus.

What makes Come and See stand out is how brilliantly and empathetically Klimov uses facts to fuel his imagination of disaster. He takes a fresh angle on the action. He zeroes in on a sad, horrific sight, like the burned face, neck and shoulders of the village elder, just when we expect him to avert his eyes. He’ll let us see the beauty of a flare soaring up into the night, like a militarized firework, before limning the ensuing havoc. His sensitivity to color and texture causes swamps and woodlands to affect us, as adults, the way the same locations in fairy tales indelibly haunted us as children.

From the moment Flyora sets foot in his mom’s now-empty house and finds her soup-pot still warm, we enter a narrative domain that mixes facts with mythic storytelling. Soon Flyora is clambering into filthy boglands and sinking into a quagmire up to his armpits, navigating what threatens to become an endless slog. Glasha staggers behind him, grabbing for his back as he functions like an icebreaker cutting through heavy muck. This mini-saga of endurance, this baptism from hell, ends when a partisan fighter named Roubej (Vladas Bagdonas) escorts them to an enclave of survivors. Here we see realistic incidents pushed to the brink of expressionism. In a fit of symbolic revenge and superstition or insanity, Roubej helps create a Hitler effigy, then carries it along when he, Flyora, and two others venture forth on a food raid.

Their journey unravels in successive calamities. One explosion after another craters the earth, like consecutive shots from a gigantic cannon—and just like that, Flyora’s and Roubej’s mates are gone, victims of land mines. In a scene that could be a jet-black parody of a frontier Western, Roubej and Flyora appropriate a collaborator’s cow and try to lead it to the starving peasants in the marsh.

Flyora, now traveling alone, gets the dubious protection of villagers who don’t realize they’re next on the Germans’ to-kill list. What follows isn’t just “total war,” but a debauch for sadists. Based on the Dirlewanger Brigade, an SS outfit made up of violent criminals, these occupiers don’t merely visit pain and grief upon the townspeople—they seek to tear away any scrap of dignity or moral worth. After they trap the population in a locked church, they announce that anyone willing to leave the children inside can crawl out through a window and go free. The Germans transform Perekhody into a circle of Hell, setting every building ablaze and exulting in each cry for help. They rape and loot under orders and on a timetable.

As the Nazis prepare their final solution for the hamlet of Perekhody, Kravchenko’s face registers relentless shocks like an emotional seismograph. The furrows on his brow harden into ridges. Then, in a climax of genius, Flyora tries to erase Hitler and his war from memory. He takes aim at the dictator’s portrait and shoots it determinedly and repeatedly as, in his mind, he projects newsreels and stills of the madman’s life in reverse, all the way back to his infancy. Flyora holds fire and breaks into tears when he envisions baby Adolf on his mother’s lap. It’s a Dostoyevskian touch: Flyora’s banked fury will not propel him into executing an innocent tot, not even one named Hitler. This decision to refrain from shooting would have made that first title, Kill Hitler, ironic. With this choice, Flyora affirms the existence of his conscience.

“Come and see” fits the movie’s evocation of a mute divinity beyond each earthly frame. In Alexievich’s Lost Witnesses, a grown man who was grade-school age during the war says, at the beginning of his testimony, “I saw what shouldn’t be seen . . . What a man shouldn’t see. And I was little.” At the end he says, “Many years have passed . . . Now I want to ask: Did God watch this? And what did He think?” Come and see.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.