Deep Focus: Alita: Battle Angel

Alita: Battle Angel (Robert Rodriguez, 2019)

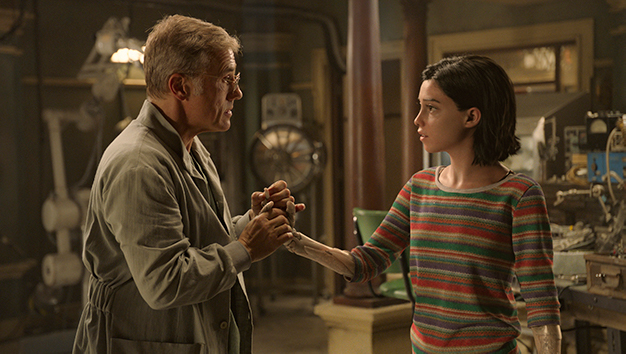

When Alita (Rosa Salazar), a sweet teenage cyborg in tumbledown Iron City, peers upward at Zalem, a pristine city in the sky, she asks her kindly surrogate father, cybersurgeon Dr. Ido (Christoph Waltz), whether “magic” keeps it floating in mid-air. Ido says the force behind it is stronger than magic: it’s “engineering.” In this lavish adaptation of the manga series by Yukito Kishiro (which debuted in 1990), producer James Cameron and director Robert Rodriguez ask, pace the Lovin’ Spoonful, “Do you believe in engineering in a young girl’s heart?” Even if the answer is yes, we may still wonder, “Should we care?”

It’s initially intriguing to see a “Total Replacement” cyborg like Alita—a human brain with a biomechatronic body—interact with Dr. Ido and a flesh-and-blood street kid named Hugo (Keean Johnson). Cameron and Rodriguez have chosen to digitize Salazar’s face with cutting-edge motion-capture technology that retains micro-reactions and nuances (like those of Andy Serkis’s Caesar in the Planet of the Apes films), so we never think we’re seeing an actor in a suit.

Unfortunately, his team has also subtly transformed Salazar’s expressive, innately dramatic features to fit the big-eyed gamine look of kitschy American portraiture. Salazar, a terrific performer of Peruvian descent, who was wonderfully gritty in her own skin in the Maze Runner movies, says, in this film’s electronic press kit, that Alita possesses all her facial characteristics, including “deep Incan-girl eye sockets. My eyes are very big and sit deep in my head.” To me, they look more like “Keane eyes,” huge, with exaggerated pupils and corneas. (Notably, Salazar’s costar Waltz played artist/con-artist Walter Keane in Tim Burton’s 2014 Big Eyes.) In Salazar’s most emotional scenes they sabotage her performance by pleading for sympathy. What might have been provocative scenes about family, romance, and the soul of a new machine come off as sentimental set pieces.

As spectacle, the film is aces. It welds Rodriguez’s eccentric touch with action and special effects to Cameron’s mastery of world-building. The 3-D is viscerally absorbing, partly because Rodriguez doesn’t shove it down our gullets. Iron City’s avenues overflow with bizarre bazaars. Cinematographer Bill Pope saturates the screen with rich colors. He captures the bustle and rude vitality of a mangy metropolis with a junkyard-dog-eat-junkyard-dog mentality. Still, eye-catching as the movie is, the mind wanders as it treks through all-too-familiar terrain. Among numerous Young Adult tropes about Alita’s love for Hugo, the only bittersweet frisson arrives when Alita reaches into her breastplate and offers Hugo her actual heart—a colorfully wired gizmo. The irony is that Hugo makes his living as a body-jacker who targets Total Replacement cyborgs like Alita—whose sole human organ is her brain—and slices off every other part. We know he’ll mend his ways after falling for Alita, but he’s too bland to be her match. His lack of originality and urgency is a drag on the movie. He’s like an affable heartthrob in an after-school special, not a precocious antihero. Instead of waiting for his transformation, we should root for him to repent soon and expose the villainy of his employer, Vector (Mahershala Ali), who controls the IC’s obsession: a gladiatorial game called Motorball. A manipulative, take-no-prisoners middleman connecting Iron City and Zalem, Vector has corrupted Dr. Ido’s ex-wife, Cherin (Jennifer Connelly), into becoming a cool clinician who tweaks Motorball’s cyborg athletes and services her boss in bed. (Ali and Connelly’s focus and intelligence elevate this material to ground level.)

Alita: Battle Angel (Robert Rodriguez, 2019)

The narrative pivots on Vector’s attempt to steal Alita’s uniquely sophisticated core technology, thought lost for 300 years. He directs a group of cyborg thugs led by the gargantuan Grewishka (Jackie Earle Haley) to hunt her down in the streets and tear her apart. When that doesn’t finish her, Vector allows her to become a top Motorball contender, before hiring ringers to crush her in a death match. Alita: Battle Angel is nothing if not ambitious. Cameron and Rodriguez want the storytelling to mesh with their construction of a sci-fi dystopia. Simultaneously, they try to retain the volatility and uncertainty of the film’s graphic-novel DNA. We should ponder whether Alita is an admirable super-heroine or a masterpiece of industrial design. After all, when she releases her inner woman warrior, her powers derive from her superb biomechatronic structure. But the film’s vision is ultimately mundane, and the script Cameron wrote with cowriter Laeta Kalogridis keeps dropping the ball.

Alita: Battle Angel lays out a routine apocalyptic backdrop while following our heroine through an ultra-traditional comic-book origin story (based on early issues of Kushiro’s manga). Dr. Ido gives his cyborg ward his late daughter’s name and outfits her with limbs and a torso he created for his child: it resembles a gorgeous Alaskan whalebone sculpture. Under stress, Alita intuitively reactivates her “Panzer Kunst” fighting skills (a high-jumping, top-kicking martial art, geared for zero gravity) and flashes back to her career as a soldier for the United Republics of Mars. She realizes her destiny when she stumbles on a “Berserker” cyborg body that melds with her nervous system.

Her arc should progress like a three-stage rocket, but it doesn’t attain liftoff, because it’s bonded to a by-now commonplace vision of a menacing future. At the start Dr. Ido rescues her from the literal scrap-heap of history. We learn that during and after a disastrous conflict known as “The Fall” (three centuries before the film begins) all the “sky cities” in the world collapsed except Zalem. This airborne metropolis became a self-styled utopia and the popular notion of paradise, while refugees from around the world formed the polyglot Iron City, where residents barter, tinker, and brawl for survival. In this Wild West atmosphere, mechanical Centurions from Zalem maintain order while licensed “hunter-warriors” (mostly elaborate cyborgs themselves) kill bad’uns for bounties. It’s a robotic rendition of the 1% and the 99%, of the haves and have-nots. Each citizen toils for the Zalem-controlled “Factory.” They repurpose the aerial city’s garbage, which plummets from a chute that extends only partway to the ground, forming a dangerous, sprawling dump. Dr. Ido regularly rummages through it for replacements to repair cyber-prosthetics. For the ground-bound, the only way to reach Zalem is to become the Motorball champ.

Alita: Battle Angel (Robert Rodriguez, 2019)

Serious playfulness soon goes missing from Alita: Battle Angel. Instead we get an unexceptional fable about bread and circuses. Zalem’s mysterious ruler Nova (an uncredited Edward Norton) has positioned Motorball to be the opiate of Iron City’s masses. But this mix of Ultimate Fighting with demolition derby, played by souped-up cyborgs on a super-fast track, basically amps up the savage roller-skating of Norman Jewison’s 1975 Rollerball. The similarities raise the old critical question, “rip-off or homage?” Vector’s order to destroy Alita in the championship game mirrors the decree of Rollerball corporate guru (John Houseman) that James Caan’s title match should be a fight to his death.

The horde of supporting cyborgs should be tantalizing, especially when the hunter-warriors gather at a saloon named “Kansas” that’s supposed to be as piquant and grotesque as the cantina in Star Wars. But only a couple are truly memorable: Ed Skrein’s vain, mohawked Sapan, and Eiza Gonzalez’s Nyssiana, a venomous, stainless-steel spider-woman. It’s amusing to think of the diminutive and talented Jackie Earle Haley playing the gargantuan Grewishka, but knowing that doesn’t enrich the behemoth’s growling and grimacing onscreen. The occasional poetic touches—like Alita slicing one of her tears in half, as it falls—go by too quickly.

Alita: Battle Angel rings some changes on the manga—not all for the best. Dr. Ido no longer gets a thrill from killing criminals, which limits Waltz’s performance and turns the character into a heart-warmer with an incongruous rocket hammer. Elsewhere Rodriguez works with over-weaning reverence. He and Cameron forget that setting up a post-apocalyptic class war in a sci-fi super-production requires more of a payoff than a fleeting triumph of the fittest in a bogus sport. Comic books and manga are more malleable forms than big-screen epics; it’s important for them to tease our expectations so we’re psyched for the next issue. The kick-off entry in a series requires a satisfying and cathartic climax. Star Wars ended with the destruction of the Death Star so the Rebel Alliance could continue, The Terminator with the crushing of the T-800 android so a future Resistance would be possible.

We feel cheated when Alita: Battle Angel ends before the heroine ascends to Zalem. What should have been transporting becomes an exercise in frustration. We never get to this film’s Emerald City.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.