Cinema ’67 Revisited: Two for the Road

In my 2008 book Pictures at a Revolution, I approached the dramatic changes in movie culture in the 1960s through the development, production, and reception of each of the five nominees for 1967’s Best Picture Academy Award: Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and Doctor Dolittle. In this biweekly column, I’m revisiting 1967 from a different angle. As the masterpieces, pathbreakers, and oddities of that landmark year reach their golden anniversaries, I’ll try to offer a sense of what it might have felt like to be an avid moviegoer 50 years ago, discovering these films as they opened.

A British couple drives across France, ten years into their marriage. Exhausted by their accumulated resentments, frustrations, and grievances, they can barely find a way to converse without weaponizing their words. “We’re not going on like this for the rest of our lives,” he mutters, half threatening, half pleading. She replies, “You haven’t been happy since the day we met, have you?” They come upon a pair of newlyweds and gaze out their car window bitterly. “They don’t look very happy,” she remarks. “Why should they?” he says. “They just got married.”

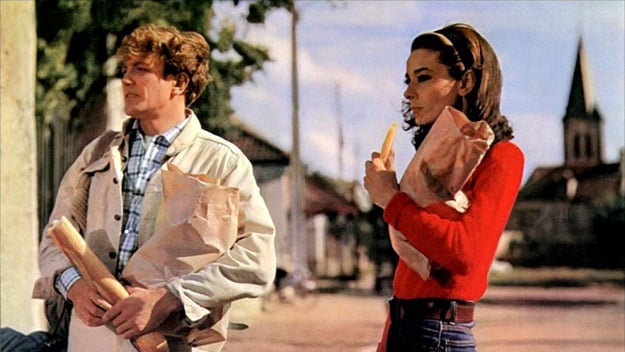

Welcome to one of the funniest, saddest, most brittle and brutal American comedies ever made about the long, long road of wedded ambivalence, with Albert Finney and Audrey Hepburn as your unassailably glamorous guides. Stanley Donen’s Two for the Road, an alternately sweet and wrenching set of scenes from a marriage was one of the first unsuitable-for-children movies ever to play at Radio City Music Hall (alongside “a salute to the Canadian Centennial and the opening of Expo 67”!). The film was not taken as the act of épater-la-bourgeoisie rebellion that many of 1967’s more famous movies were felt to embody, but the sting of Frederic Raphael’s Oscar-nominated screenplay is as acute as any movie of the era, and the sophistication of its structure remains remarkable.

Two for the Road, a portrait of a couple examining the wreckage they’ve created along the way as they come to a pivotal I-can’t-go-on-I’ll-go-on moment in their relationship, unfolds as an ingeniously braided series of road trips taken by husband Mark Wallace (Finney) and wife Joanna (Hepburn): one in the present, as they sulk, mourn, lash out, and contemplate what feels like the finish line; another a dozen years earlier, when Mark, a then-aspiring architect, meets and woos his virgin bride (amazingly, Hepburn, 37 and headed for divorce during production, just about pulls those scenes off). There’s also a sojourn that turns into a hilarious literal car wreck when they’re newlyweds, a business trip in which infidelities rear up, and a joint vacation spent in the company of two terrible Yanks (William Daniels and Eleanor Bron, bringing theater-pro savagery to their caricatures of self-styled modern-minded Americans of the day) who have an equally terrible small daughter. The sequences don’t unfold in any apparently preordained order; they cut into and out of one another intuitively, with a gesture or a hurt feeling or a happy moment triggering a memory of its equal or its opposite years earlier, or later. The road always looks the same, though. And the journey never ends. “What we were trying to do,” said Donen later, “was to say, all sequences in this movie are the present. Everything you see in their life is carried with them from the beginning of their relationship to the end.”

It was an unlikely four-way match: the director of Singin’ in the Rain with the Academy Award-winning writer of John Schlesinger’s Darling, and the brash, beefy star of Tom Jones with the actress who epitomized Hollywood elegance and delicacy (and who usually worked with leading men—like Fred Astaire, Cary Grant, and Rex Harrison—who were decades older, not, as Finney was, seven years younger). Nonetheless it all worked. Raphael had a great ear for quietly caustic give-and-take:

Mark: I just wish you’d stop sniping.

Joanna: I haven’t said a word.

Mark: Just because you use a silencer doesn’t mean you’re not a sniper.

And Donen knew just how to have his stars play those lines—with the understated rue of a pair of people who perform unhappiness for each other as a way of disguising the real pain beneath. Two for the Road is the rare movie that let Hepburn be a fully adult, sexual woman, and she gives her most fully realized and shaded performance in it. It helps that Raphael spread the good lines around equally. When Joanna tells Mark she’s pregnant, her husband, who trades heavily on loutish charm but increasingly has trouble striking a balance between those qualities, looks at her baitingly and says, “I’m trying to imagine you fat.” She looks back at him and levelly replies, “I’m trying to imagine you thin.”

Of course Finney and Hepburn fell for each other during production. How could they not? “During a scene with her,” Finney said later, “my mind knew I was acting but my heart didn’t, and my body certainly didn’t . . . I won’t discuss it more because of the degree of intimacy involved.” The chemistry between the two is unmistakable, and perhaps at its most powerful during the scenes when you’re wondering whether Mark and Joanna should stay together at all. And Donen gives their dilemma a great glossy coat—from the gorgeous animated opening credits by 007 genius Maurice Binder to what may be the most melancholy romantic theme Henry Mancini ever composed to the profligate costume credit, which reads, “Miss Hepburn’s clothes by Ken Scott, Michele Rosier, Paco Rabanne, Mary Quant, Foale and Tuffin, and others.” Under Donen’s steady hand, Two for the Road does what only a Hollywood movie can do: it convinces you that two beautiful movie stars tooling through France in a car are just like us. It’s everybody’s marriage that’s on trial in this film—if you have ever failed to let a fight go or said one thing too many or kept silent rather than apologized, you’re likely to recognize a bit of yourself in the shards of the Wallaces.

Critics embraced Hepburn’s work (though her Oscar nomination that year would come for a more traditional woman-in-jeopardy role in Wait Until Dark), but they were less fond of Finney. Raphael himself complained that his leading man “never understood…that you’re very lucky to be with a beautiful woman. Perhaps he’d been spoiled.” Indeed, for much of the movie, Mark is the embodiment of unearned self-regard, not to mention bellicose sexism, and “What can she possibly see in him?” would be a legitimate question if the thunderingly obvious answer weren’t, “For God’s sake, he’s Albert Finney at 30!” Even when he’s telling Hepburn things like “Your nicely brought-up American girl may play it cool and modern, but what she wants is what her grandmother wanted: your head stuffed and mounted on the living room wall,” it’s mitigated by the facts that a) Hepburn is cool and modern, and not just playing at it, and punctuates the line with a deft and jolting visual dirty joke; and b) Finney is a smart enough actor to know that Mark is mostly bluffing.

Even in 1967, Two for the Road had a hard time getting to the screen. When Raphael’s script was submitted for approval two years earlier, the Production Code was ailing but not yet dead, and its overseer, Geoffrey Shurlock, found much to complain about. After a meeting he wrote in a cautioning memo that “the premarital sex relationship between Mark and Joanna is, in our opinion, condoned and justified and not presented within the moral framework required by the Code when treating such a relationship. Also, there is an abundance of vulgar dialogue, which in itself would result in an unacceptable picture…Possibly… dialogue could be inserted which would state that perhaps Joanna and Mark would not find their lives in such a mess at this point if they had not indulged themselves so freely before their marriage…We feel it most important that you do not end the picture with the two expressions ‘bitch’ and ‘bastard.’”

And yet, that is how it ends, and in context it’s actually a welcome note of optimism. Two for the Road did not ignore the warnings from the Production Code office so much as it outlasted them. By the time the film was released, the Code was almost dead, but the ratings system that would replace it had not yet been inaugurated. Donen and Raphael didn’t have to change a thing, and the Code grudgingly approved the picture, albeit with the then-unusual label “Suggested for Mature Audiences.” That warning still holds true. Donen had made a movie for adults—and it remains one of the finest of its genre and of its era. “There’ll never be anyone else like you in my life,” Joanna tells Mark at one point. “You promise?” he says. “I hope,” she replies. The moment is both wounding and tender. So is the movie.

How to see it: Two for the Road is available on DVD and (expensively) on Blu-ray, and also streams on Amazon and iTunes. For the obsessive or curious, a fascinating chronological fan re-edit of the film can be found on Vimeo.

Mark Harris is the author of Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood (2008) and Five Came Back (2014).