Cinema ’67 Revisited: Portrait of Jason

In my 2008 book Pictures at a Revolution, I approached the dramatic changes in movie culture in the 1960s through the development, production, and reception of each of the five nominees for 1967’s Best Picture Academy Award: Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and Doctor Dolittle. In this biweekly column, I’m revisiting 1967 from a different angle. As the masterpieces, pathbreakers, and oddities of that landmark year reach their golden anniversaries, I’ll try to offer a sense of what it might have felt like to be an avid moviegoer 50 years ago, discovering these films as they opened.

On Dec. 3, 1966, the documentary filmmaker Shirley Clarke turned her cameras on a gay African-African aspiring performer named Jason Holliday. The “when” is crucial to any real understanding of the transfixing, troubling, immensely powerful documentary that resulted. This was three years before Stonewall; two years before the movies looked sneeringly at lesbians and their presumably sham “marriages” in The Killing of Sister George; one year before Mike Wallace, on the “CBS Reports” special The Homosexuals (whose subjects were interviewed in silhouette), called homosexuality an “enigma” and cited a poll showing that most Americans thought it was more harmful to society than adultery or prostitution. When Portrait of Jason opened in 1967, homosexuality was still being scrubbed from most Hollywood movies (even the makers of the year’s most daring studio film, Bonnie and Clyde, removed Clyde’s bisexuality from the script shortly before production). And as Vito Russo’s The Celluloid Closet made clear, when gay characters did appear on screen, their murders or suicides generally followed within three or four reels. In this context, it isn’t hard to understand why Russo himself wrote that “two hours with Jason Holliday is like a month in another country.”

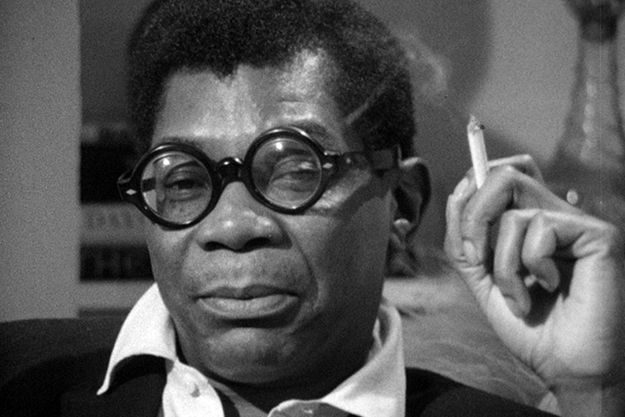

From today’s perspective, as the movie begins, Portrait of Jason seems less like a vacation from American reality than a rocket ship into the future of gay liberation. Dapper, blazered Jason Holliday—he’s on camera, drink(s) and cigarette(s) in hand, for the entire film—is unlike any gay man who had ever been seen in a movie before. He’s amusing, profane, explicit, and—most startlingly for the time—seemingly without shame, reservation, or embarrassment. In the first moments, he tells us—lushly embroidering each phrase with his knowing, droll delivery—that his real name is Aaron Payne. “‘Jason Holliday’ was created in San Francisco,” he says. “And San Francisco is a place to be created, believe me.” It’s not just the words that would have startled audiences in 1967; it’s the unfurtive, self-amused delight with which he serves them up. Jason goes on to recount his life as a houseboy, a hustler who has “balled from Maine to Mexico,” a traveler, a would-be nightclub performer, an acquaintance of Miles Davis and of Andy Warhol, a drag artist, and most notably, a born storyteller whose winding, cutting monologue is, we come to realize, a profound and fiercely courageous act of self-invention and self-sustenance.

In the early beats of the movie, Jason is, above all, great company, an expert host throwing a party for himself. “I am doing what I want to do,” he says, “and it’s a nice feeling that somebody’s taking a picture of it! This is a picture I can save forever…one beautiful something of my own. For once in my life, I was together, and this was the result of it.”

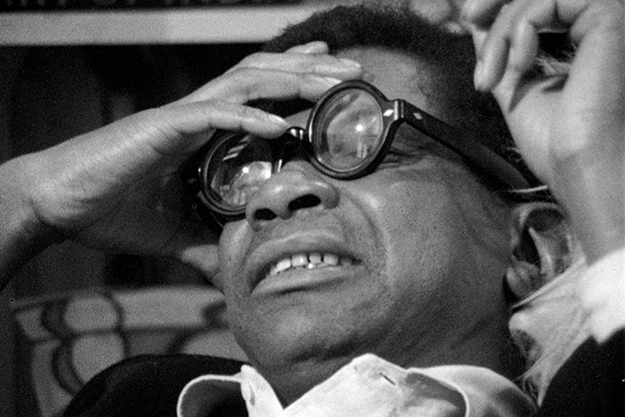

The degree to which Clarke actively seeks to undermine that high is what makes Portrait of Jason one of the few films to be as divisive in 2017 as it was in 1967. Her portrait of Jason Holliday attempts to trace the arc of an alcohol-aided breakdown. Jason, during the course of an evidently long and sodden evening, gets ever drunker. As he loosens up enough to unveil his impression of Mae West and his recreation of a long section of Carmen Jones (“What else you got?” we hear an unimpressed Clarke say), he becomes blurrier and slurrier, which Clarke emphasizes by having the camera deliberately take him out of focus. It becomes clear that she’s looking for a rock-bottom, and when he hits it, her job is done. It is hard to watch Portrait of Jason and not feel that Clarke has an appetite for the stripping-away of self-delusion, and/or a belief that under the merciless eye of her vérité camera, all of Jason’s poise and performativity will eventually burn off to reveal what’s real and tragic.

Portrait of Jason’s detractors seized on this, then and now. Pauline Kael called it “sadistic and naïve.” Fifty years on, the discussion is more about homophobia and othering. Clarke was a white filmmaker whose primary focus in the 1960s was on African-American subjects; she had made The Connection, about heroin addiction, in 1961, and The Cool World, about gangs, in 1964. In 2015, a divisive indie film called Jason and Shirley, which dramatized the making of Portrait of Jason, essentially portrayed Clarke as a somewhat ruthless cultural tourist. And Clarke (who died in 1997, one year before Holliday) did herself no favors by admitting, in a 1983 interview, “I started that evening with hatred, and there was a part of me that was out to do him in.”

Holliday himself claimed at least once that his emotional collapse in the film was a performance piece of which he was in control. That feels unlikely, but the impulse behind his assertion—a desire to claim agency, independence, and authorship—is what makes Portrait of Jason such an enduringly fascinating film. Whatever Clarke’s desires were walking in (or, at least as importantly, in the editing room), she didn’t come close to destroying Holliday, who pretty much fights her to a draw. He may have been a sloppy drunk, but Clarke’s insistence that booze lays bare your soul now feels like the most dated part of the film. (I can’t help noting that she took her cameras off to shoot Holliday just six months after Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? opened in movie theaters. It seems to have left a strong impression.)

Holliday himself called Portrait of Jason a stalemate: “I think the chick and me are even, dig it?” he told Jonas Mekas in a 1967 interview. More today than when the film was released, his very presence onscreen feels like a bold political act, and his words an absolute rejection of invisibility. And crucially, Clarke, who was, despite her professed antagonism, a serious and thoughtful filmmaker, gives us enough of Jason at his best for us to be able to resent the film’s eagerness to show him at its worst. The film concludes with Clarke singsonging, “The end, the end, the end, the end. The end. That’s it. It’s over. The end.” But what resonates now about Portrait of Jason is that it wasn’t her call. Jason, one beautiful something of his own, lives to fight another day.

How to see it: A restored version of Portrait of Jason is available on DVD and Blu-ray from Milestone Films, and streams on Amazon Video.

Mark Harris is the author of Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood (2008) and Five Came Back (2014).