Cinema ’67 Revisited: The Battle of Algiers

In my 2008 book Pictures at a Revolution, I approached the dramatic changes in movie culture in the 1960s through the development, production, and reception of each of the five nominees for 1967’s Best Picture Academy Award: Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and Doctor Dolittle. In this biweekly column, I’m revisiting 1967 from a different angle. As the masterpieces, pathbreakers, and oddities of that landmark year reach their golden anniversaries, I’ll try to offer a sense of what it might have felt like to be an avid moviegoer 50 years ago, discovering these films as they opened.

No great movie of the 1960s had a longer, stranger trip into the consciousness of American filmgoers than The Battle of Algiers. Gillo Pontecorvo’s thrilling, tough-minded, documentary-style depiction of Algeria’s fight for independence from France had its premiere in August 1966 at the Venice Film Festival, where it won the Golden Lion over the furious protests of the festival’s French contingent. Months later, it earned an Academy Award nomination as Italy’s submission for Best Foreign-Language Film. In September 1967—more than a year after its European debut—the movie served as the opening-night selection for the New York Film Festival, then in its fifth year. The next day, it opened theatrically in New York, and then gradually across the country—so gradually, in fact, that it didn’t reach Los Angeles until early 1968, when (under Academy rules that have long been revoked) it became, in effect, re-eligible for awards. In early 1969, almost three years after Venice, The Battle of Algiers received two more Oscar nominations, one for Pontecorvo’s direction and one for the screenplay he cowrote with Franco Solinas. It remains the only movie in Oscar history to garner nominations in nonconsecutive years. (The film’s first French theatrical engagement would not come until 1971; bomb threats had thwarted its Paris opening in 1970.)

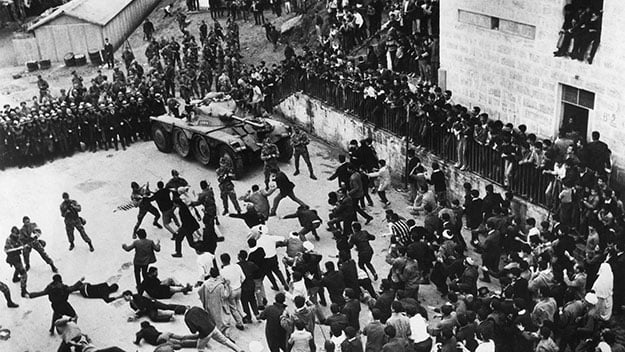

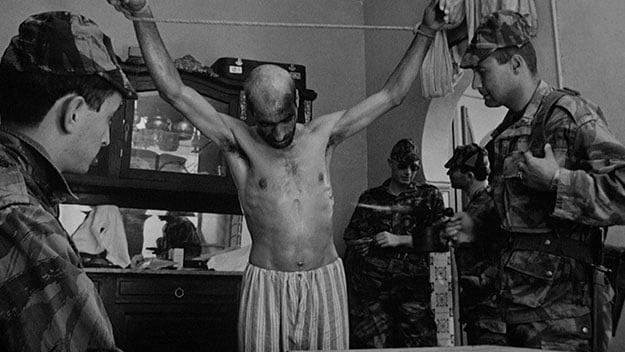

The Battle of Algiers may have been slow to arrive, but once it was here, it put down roots. Pontecorvo’s work felt—and still feels—like a radical document, a bulletin from the front that blazed straight into the middle of a left debate about when violence is permissible in a revolution and what guerrilla tactics young American protestors might adapt. The film’s relevance was lost on nobody—when it opened, even The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther, who could so frequently be stodgy about aesthetically bold films but was not oblivious to their politics, praised its verisimilitude and passion and noted that “essentially, the theme here is…the valor of people who fight for liberation from economic and political oppression…one may sense a relation…to what has happened in the Negro ghettoes of some of our American cities.” Soon after, Newsweek’s Joseph Morgenstern noted that “at a first-run theater on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, many young Negroes cheered or laughed knowingly during each terrorist attack on the French, as if The Battle of Algiers were a textbook and a prophecy of urban guerrilla warfare.” By the third year of its run—after opening, the film was almost always on a screen somewhere in New York well past the end of the 1960s—the Times noted that it had been “adopted by certain radical groups in this country as a model” and Pauline Kael, writing in November 1970, wrote that “in the last two years [it] has become known as the black militants’ training film.”

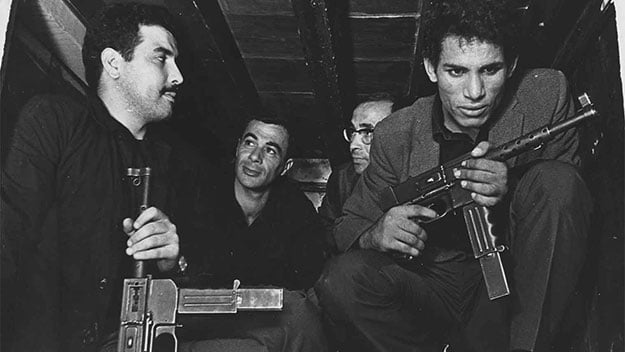

Fifty years later, it remains remarkably easy to see what all the fuss was about. While docudrama recreations of real events are much more common today than they were in 1967, the lack of familiar faces in The Battle of Algiers may still make you wonder, as many critics did back then, if some of what you’re seeing is found footage. It’s not, and in retrospect, Pontecorvo was extraordinarily fortunate that his initial vision for the movie—in which the story of the Algerian struggle would be told through the eyes of an American journalist to be played by Paul Newman—could not be realized. Pontecorvo himself was not the first choice to direct. According to a Criterion Collection supplement, the Algerian government, seeking someone to adapt a memoir by imprisoned military leader Saadi Yacef (a non-actor who became the film’s impressively persuasive costar), approached Pontecorvo only after getting turndowns from Francesco Rosi and Luchino Visconti.

Nothing on Pontecorvo’s resume suggested he was the right man for the job. A onetime Communist and secular Jew, he had made his name with the 1960 concentration-camp drama Kapo, which had been nominated for Best Foreign-Language Film but was dismissed by many critics as glib and melodramatic. The technical proficiency of The Battle of Algiers—a kind of polished rawness, with black-and-white footage at once impeccably framed and seemingly captured on the fly—was a first for him. And the script’s tone, a shrewd balancing act that manages to avoid the twin extremes of preaching-to-the-choir propaganda and blandly evenhanded “both sides”-ism, makes it an enduringly worthy object of study for political filmmakers today. Although Pontecorvo’s sympathies are clear, his vision is remarkably unromanticized, and the violence, which is copious, is depicted bluntly enough so that viewers cannot avoid confronting it. More than any film of its kind, The Battle of Algiers, in its two packed hours, creates a sense of escalation, an understanding of the rhythm by which an uprising, a resistance, a protest can move from David-vs.-Goliath conflict to crisis to war.

The film’s arrival and reception seemed to herald the beginning of a major new career for the 47-year-old Pontecorvo. It was not to be. In 1969, the director, who had drawn the admiring attention of Marlon Brando, went to Hollywood and expended all the capital Algiers had brought him on Burn!, another story of anti-colonial revolution that proved to be a massive flop. He never made another film of note, and spent much of the remainder of his career shooting TV commercials. (He died in 2006.) Yet few directors can rest their reputations more securely on a single work. The Battle of Algiers remains not only a landmark of engaged political filmmaking but also a template for it.

How to see it: The Battle of Algiers is currently available on Filmstruck as part of a special Academy Award collection on winners of and nominees for Best Foreign Language Film, from Mon Oncle to Rashomon to Dogtooth. It is also available on DVD and Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection.

Mark Harris is the author of Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood (2008) and Five Came Back (2014).