Cannes Report #3: Wonderstruck

Todd Haynes with his cast and collaborators on Wonderstruck. Photo by Eugene Hernandez

Watching Todd Haynes’s seventh feature, Wonderstruck, it’s hard not to think about certain hallmarks of the director’s previous films: the sense of yearning and isolation found in Safe and Far from Heaven; the fixation on personal and historical past as characters come to terms with being outsiders in Velvet Goldmine; even the use of Barbie dolls as stand-ins for real people in Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story. His new film pulls from familiar aspects of the Haynes universe, but stands apart as a singular work and one of the best films of the year so far.

Wonderstruck premiered in competition on the second day of the Cannes Film Festival. It tells the parallel stories of two deaf preteens—one living in 1927 and the other in 1977—who embark on solitary adventures to New York City, seeking truths about their personal pasts. They ultimately find answers and inspiration at the American Museum of Natural History. Dioramas inside that museum play a key narrative role, as does the Queens Museum’s Panorama of the City of New York—a miniature model of the city built for the 1964 World’s Fair that becomes the centerpiece of a stunning, handcrafted sequence. “This film is a tribute to what you do with your hands, with your fingers,” Haynes explained at the press conference, referring to the crucial role of these miniatures in unlocking the mysteries of the movie as well as to the sign language used by the young characters.

“A sort of metaphysical time travel” is how Haynes referred to the movie and said that he was drawn to the story because “it focuses on the imagination of kids. It is constructed as a true mystery.” The visually arresting film cuts back and forth between the two children’s stories, their separate timelines evoked via sounds and images from period-specific music and movies. It also features extended dialogue-free sequences, relying on music and image to propel a narrative that manages to be deeply emotional instead of technically alienating. “The formal conceit is at the core of the mystery,” he explained. “It pulls the viewer through the story.”

Wonderstruck

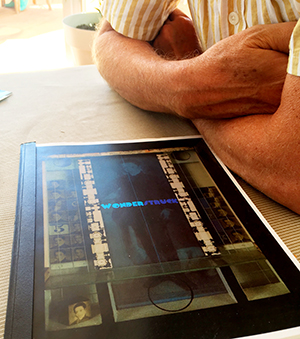

Haynes shares his achievement with a team of recurring collaborators—costume designer Sandy Powell, cinematographer Ed Lachman, editor Affonso Gonçalves, production designer Mark Friedberg, and composer Carter Burwell. “I now have this company of hands-on artisans and creative people who really feel like extensions of my own proclivities,” Haynes said in a one-on-one conversation with Film Comment at a beachside café. At one point during the discussion, he grabbed his backpack and pulled out a lookbook of images that he gathered to inspire his collaborators while preparing the film. It includes single shots from other movies and archival photos of New York City from the ’20s and ’70s, among other research materials.

“There’s a lot of formalist complexity in this conceit, the style, the double narratives, [and] the editorial body of the movie,” Haynes reflected, adding, “It’s all in Brian’s book”—meaning Brian Selznick’s 2011 illustrated young-adult novel Wonderstruck. Selznick, best known for The Invention of Hugo Cabret, brought to the screen by Martin Scorsese in 2011 as Hugo, spoke at the film’s press conference about adapting his book into a screenplay. “It was an intensely cinematic idea on the page,” Selznick said, and to visually animate the work, he illustrated the script in both color and black and white.

After effectively shooting distinct movies for each kid’s journey, Haynes worked with his editor to establish the right pace for combining the two. “It really came together as a breathing entity in the editing room,” Haynes remembered, elaborating that he and Gonçalves screened early cuts for children, so they could see how it would ultimately play with younger viewers. “They kept guiding us and helped us to determine when we would make the transition to one of the stories,” Haynes noted. “It really was a journey that was editorial in nature.”

Todd Haynes, in Cannes, with his look book from Wonderstruck. Photo by Eugene Hernandez

In a period movie that uses sound and music to distinguish its eras, Haynes leaned on key pop songs to establish tone—for the ’70s, he cues up David Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” Esther Phillips’s “All the Way Down,” Rose Royce’s “Sunrise,” Sweet’s “Fox on the Run,” and a spectacular deployment of Eumir Deodato’s 1973 jazz-funk take on Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra. And then there’s Carter Burwell’s score, which shifts style to suit each timeline. Haynes said that he created a playlist of songs and music to accompany the lookbook, helping to further immerse himself and his team in the given historical periods.

“There are many reasons why the past continues to inform us and motivate me,” Haynes offered during the press conference. Struck by this comment, I asked him to elaborate during our more intimate conversation a few days later. “Maybe it’s always feeling a slight disillusionment in the present,” Haynes began, pensively. “Jeepers, I wonder why I would feel that right now? But I also feel, every time, I become a sort of student of the past in any movie. I don’t ever want to stop learning about movies, history, and culture. And each one becomes an assignment to do just that, to basically feel like you are living through that time yourself, because every conceivable part of it has to be re-created and you want to feel comfortable in its skin.”

As he was talking, Haynes referred back to the lookbook: “It’s always a construct, but it’s about as close as you can get to stepping back through time.”