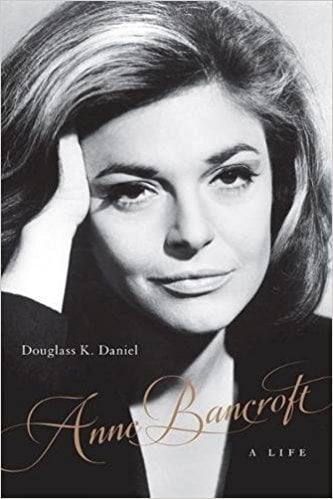

Readings: Anne Bancroft: A Life

Anne Bancroft embodied two qualities that were nowhere near as diametrically opposed as they seem at first glance: the sensuality of a beautiful woman used to commanding any room she entered, and the zero-to-60-in-three-seconds-flat capacity for rage of someone born Anna Marie Louise Italiano in the Bronx. Douglass K. Daniel, who previously wrote an excellent biography of Richard Brooks, has written an overdue, finely detailed portrait of the woman who combined those apparently competing strains in Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate.

Anne Bancroft embodied two qualities that were nowhere near as diametrically opposed as they seem at first glance: the sensuality of a beautiful woman used to commanding any room she entered, and the zero-to-60-in-three-seconds-flat capacity for rage of someone born Anna Marie Louise Italiano in the Bronx. Douglass K. Daniel, who previously wrote an excellent biography of Richard Brooks, has written an overdue, finely detailed portrait of the woman who combined those apparently competing strains in Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate.

The best actors always communicate multiple layers with or without the help of the script, and Bancroft’s Mrs. Robinson is funny, alluring, and aware enough to be awash in self-loathing over her own wretched choices. Until the screenplay forces her to turn into a cliché virago at the climax, she’s by far the most compelling character in the movie.

You will be glad to know that Daniel’s Bancroft is calmer and more sympathetic than the Bancroft described in Frank Langella’s memoir Dropped Names. Langella’s Bancroft carries a perpetual edge that eventually drove many people away, including Langella, but then he doesn’t exactly project a warm campfire of nurturing emotion either.

Gorilla at Large

You couldn’t blame her for being touchy. Starting out in the 1950s, Bancroft had to endure all the finely graded humiliations of an actress with an ethnic background and no obvious niche. When she was signed by Fox in 1951, Darryl Zanuck handed her a list from which she could choose a new name. She thought that most of the choices sounded cheap. “Bancroft was the only name that didn’t make me sound like a bubble dancer,” she said.

To put it as delicately as possible, the studios didn’t know what to do with her, and the embarrassment began. She played an Indian maiden opposite Audie Murphy, and endured 1954’s Gorilla at Large. To save her creative life, she had to return to the stage and play Annie Sullivan in The Miracle Worker, Gittel Mosca in Two for the Seesaw opposite Henry Fonda, and Brecht’s Mother Courage. Movie audiences may have wrenched their necks at her performance in The Graduate, but in New York they looked and applauded and said, “Well, that’s Annie.”

Even though she had definitively demonstrated her chops—and gotten an Oscar for Arthur Penn’s 1962 adaptation of The Miracle Worker—Hollywood continued to play her cheap by casting Shirley MacLaine in the botched movie version of Two for the Seesaw, thereby eliminating the dramatic tension between the Jewish Gittel and her WASP lover.

The Graduate

What’s interesting about Bancroft is not her temperament, but her intelligence and her choices. Any woman who could have a successful marriage with Mel Brooks could not lack for humor, not to mention stamina—comedians are exhausting. After The Graduate, she didn’t make another movie for five years, more or less because she had no desire to play a succession of horny middle-aged women. She turned down The Go-Between with a stunned “You want me to play Julie Christie’s mother?”

Temperament was only called upon when absolutely necessary. When she was rehearsing a play in the summer of 1968, the heat was unusually oppressive and the rehearsal hall was not air-conditioned. Bancroft put up with it for a few days, then said to the producers, “We really can’t work like this. You’ve got to air-condition this place.”

“That won’t work,” she was told. “Forget it.”

To which she replied, “I think you’ll find a way,” and walked out.

The next day there was a truck with a large portable air conditioning unit parked outside, and the rehearsal hall was comfortable.

“She was Annie Italiano,” a friend tells Daniel. “She was just a good old girl who grew up on the streets of New York,” a sentiment repeated throughout Daniel’s book in different wordings from different people, including her sister.

The Elephant Man

When Bancroft finally went back to work, it was as Jennie Jerome in Richard Attenborough’s Young Winston (1972), the first taste of the self-regarding gentility that she would also project in The Elephant Man (1980) for David Lynch. Other times she would relax and let her Bronx show: Jack Lemmon’s harried wife in The Prisoner of Second Avenue (1975), a tempestuous retired ballerina in The Turning Point (1977), a rapt bibliophile in 84 Charing Cross Road (1987), as well as a touching turn in a little-seen, sentimental Sidney Lumet movie from 1984 called Garbo Talks. (The problem might have been in the collision between Sidney Lumet and “sentimental.”)

Daniel includes numerous delicious anecdotes attesting to Bancroft’s savvy about acting and character. When she appeared in a 1967 production of The Little Foxes for Mike Nichols, she guided Austin Pendleton out of a psychological box that was slamming shut after Nichols unhelpfully told him, “How can I give notes on a performance that is wrong from beginning to end?”

Understandably stunned, Pendleton assumed he was going to be fired, when Bancroft took him aside. The problem, she said, was his walk. Pendleton was playing Leo—the stupid, entitled character Dan Duryea played in the movie version of Lillian Hellman’s play. Pendleton was a smart man who thought of himself that way and was using his own walk: leading with his head. But Bancroft said that Leo’s ego would lead him to walk by fronting his groin. She then demonstrated her idea of Leo’s walk. The different walk completely changed Pendleton’s approach to the character and Nichols’s objections melted away.

Eventually, Bancroft tried directing, a not-bad little movie called Fatso (1980), about a binge eater starring Dom DeLuise, but she found she didn’t like it. “She hated the actors,” was the way Mel Brooks put it.

All actors do.

Scott Eyman has written 15 books about the movies. His latest, Hank and Jim, the story of the friendship between Henry Fonda and James Stewart, will be published in October.