Bombast: Punking Out

We Are the Best! is wrapping up the second week of its New York run, having engendered enough positive press and word of mouth to ensure itself a happy VOD afterlife. (A typical note, struck by the reviewer for The Guardian: “When was the last time you left a cinema wanting to hug everyone involved in the film you just watched?”) The film, Lukas Moodysson’s first in four years, was adapted from a 2008 graphic novel called Never Goodnight, a firsthand reminiscence of punking out in early-Eighties Sweden by Coco Moodysson. (Its identification character is, not coincidentally, named “Bobo.”) It follows the formation of a punk trio in Stockholm in 1982 by three girls on the edge of adolescence, and the subsequent adversities that they face. Lukas and Coco, who are husband and wife, were born in 1969 and 1970 respectively, and are of age to remember the period, the texture of which the movie gets down with scrupulous attention, while the girls’ misadventures are soundtracked with exhumed seven-inches including KSMB’s “Sex Noll Två.”

We Are the Best!

I saw We Are the Best! a couple of months ago when it was making the festival rounds, but only felt any urge to write about it after reading Richard Brody’s takedown, titled “Shiny, Happy, Fake Sweden,” in his New Yorker–hosted blog The Front Row. I find more of value in the movie than Brody does, but I’m not picking up the topic because of any overwhelming desire to stick up for it—as he notes, WAtB!, which is enjoying near-unanimous approval according to review aggregators, doesn’t lack for defenders. I’m interested, rather, in looking at how the movie interfaces with the musical and social phenomenon of punk rock, and where it fits within the context of the punk-rock movie.

Brody’s objection to We Are the Best! is based in a belief that it feeds “fantasies of a virtually infinite tolerance,” noting how easy everything appears to be for punks in Sweden, where rebellion takes place in state-sponsored comfort, with the local youth center providing the kids a rehearsal space and instruments, and even lining up an out-of-town gig so that they can lap up the exhilaration of a hostile crowd’s boos, although without too much risk of things getting really out of line.

The timeline is important here. Pop-culture years are like dog years for the young, so 1982 is roughly a half-century removed from 1977. This means that the girls, played by Mira Barkhammer (tomboy Bobo), Mira Grosin (spark-plug Klara), and Liv LeMoyne (Christian-convert Hedvig), aren’t on the front lines of anything. The girls’ classmates aren’t freaked out by their Renée Falconetti haircuts—they’re condescending, making a show of just how not shocked they are, for fashion has moved on from punk while the girls have not. (Klara’s older brother, a former punker, has since lost his liberty spikes and graduated to Joy Division.)

Where We are the Best! has been second-guessed elsewhere, it’s usually on the grounds of the film’s introducing friction by way of boy trouble, which begins when the trio cold-call the members of a band based in a neighboring town and take a train out to meet them. Everything that leads up to the meeting, it should be said, feels absolutely true, for the isolation of belonging to a minority subcultural identity can lead to a heedless reaching out towards anyone anywhere nearby who’s part of the same tribe, a trust both quaintly touching and, sometimes, dangerous. That danger isn’t a factor here: the boys in the band are contemporaries, equally inexperienced, and the only thing that’s on the line is a bit of puppy-love heartache. What doesn’t come into play is the fact that punk, being a magnet for youthful rebellion, is also a refuge for unsavory old dudes, scene vets perfectly willing to flatter adolescents with the fact that someone older seems to be taking them seriously, and take advantage of their stature.

If we were watching three girls with shaved heads playing punk shows somewhere in Sweden outside of a large and cosmopolitan city, we might have a very different and more troubling movie on our hands, and in 2014 there are surely places in these United States where showing up for school with your hair dyed pink is still an open affront and an invitation for passing motorists to peg you with insults and empties when you’re on your way home. Bobo, Klara, and Hedvig escape most of that sort of flak, in part because of their extreme youth, which is a sticking point for Ebert.com reviewer Godfrey Cheshire, whose two-star review complains that the Moodyssons’ focus on such young subjects “effectively infantilizes punk.” (Fine, but I’ll bet you a copy of Old Skull’s Get Outta School that infantilization has always been part of punk’s arsenal of offenses.)

I’m not inclined to chastise the Moodyssons for making a movie that showcases their version of what punk is or was or could’ve been—here, a space outside of official adult and school culture in which to craft an identity and foster a sense of self-worth—rather than another. Why, though, should We Are the Best! be about punk rather than any other niche extracurricular hobby? I’m not sure that it makes much difference that it is. If anything, showing the application of punk’s universal prescription for disobedience to a particularly Swedish context may say more about national culture than the subculture. Perhaps the defining aspect of rebellion in wealthy Scandinavian countries, where a base-level prosperity is virtually guaranteed by small populations and a surfeit of natural materials, and where permissiveness is woven into the fabric of national identity, is the invention of an enemy—see the xenophobia of Norwegian Black Metal, based on a fantasy of encroaching foreign hordes in what is in actual fact one of the most uniform gene pools on the planet.

The defiant healthiness of We Are the Best! puts it at odds with the punk movies made during the period that it depicts, in which punking out is depicted as a variety of acting out, a reflexive response to fraying social fabric and insupportable home life by Kids of the Black Hole. The hippie-generation parents in WAtB! are alternately distracted and doofy, but there’s little sense that any of their benign neglect is going to lead to genuine depredation, a point underscored by scenes of the girls spare-changing.

The punk-rock movie constitutes a subgenre unto itself, to which We Are the Best! putatively belongs—for our purposes, I am talking about movies that have punk rockers (as classically understood), rather than movies which might be said to express a punk attitude, like Robert Bresson’s The Devil, Probably, which no less an authority than Richard Hell called “by far the most punk movie ever made.” Thinking of fiction features contemporary to We Are the Best!’s “Reagan Brezhnev fuck off!” period, I turn immediately to Penelope Spheeris’s Suburbia (1983) and Dennis Hopper’s Out of the Blue (1980).

Say what you will about Suburbia, it doesn’t stint on the sense of youth in danger: within the film’s first five minutes, we see a toddler being fatally mauled by a stray Doberman pinscher! My friends and I used to get quite a larf out of Spheeris’s movie when I was a young punk myself, particularly from quoting the maladroit line readings by scenesters-cum-actors like skinhead Timothy O’Brien (“You. And. Your. Drugs. This. Is. What. I. Think. Of. Your. Drugs.”) and Michael “Flea” Balzary. Also greatly cherished was a scene at a D.I. show where, during a performance of “Richard Hung Himself,” a New Wave pixie who has obviously wandered into the wrong venue has her clothes ripped off by the crowd, and is left naked in the middle of a jeering circle to shriek in hysterics while singer Casey Royer helplessly upbraids the perps from the stage. (“Leave her alone you homos… Perfect example of a punk rock aggressiveness.”) My friends and I dismissed this as punksploitation sensationalism—the movie was produced by Roger Corman for his New World Pictures, after all, and could therefore be expected to have roughly the same relationship to real hardcore punk as Bucket of Blood had to the Village Beat scene. But writer-director Spheeris had been on the front lines of California hardcore c. 1980 while filming her documentary The Decline of Western Civilization, and even if the staging of the assault at the show feels utterly false in every detail, it’s very likely that Spheeris knew something we didn’t about the sexual bullying and general loutishness that went on in the scene at that time.

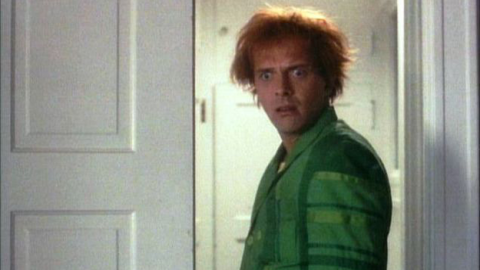

Out of the Blue

“Punk is not sexual,” says Linda Manz’s Cebe in Out of the Blue, to no one in particular. “It’s just aggression.” (If you haven’t seen the movie, maybe you’ve heard the sound bite on the song “Kill All Hippies” from Primal Scream’s XTRMNTR album.) She’s sitting in the cab of a wrecked 18-wheeler, sending out messages in a bottle via the CB radio, which is where her nickname comes from. (Her truck driver father, away in the slammer when the movie starts, left her with the handle, and a hefty freight of psychological problems.) Out of the Blue was Hopper’s first directing job since The Last Movie in 1971, and one that he backed his way into, though it seems tailor-made to the concerns of a man who worshipped at the altar of James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause. In the period preceding the shoot, Hopper had been in Mexico City trying to set up an adaptation of B. Traven’s The Death Ship, investigating the decease of the mysterious German author and ingesting God-knows-what his free time. Hopper was signed on to play Cebe’s father in the movie, originally titled Cebe, but when co-scenarist and first-time director Leonard Yakir was yanked eight days into the shoot, producer Paul Lewis, who’d worked with Hopper on both Easy Rider and The Last Movie, slotted Hopper into the director’s chair, and apparently signed off on his flying in his Last Movie survivor Don Gordon for a part and rewriting the script to minimize the role of Canadian earthquake Raymond Burr as a child psychiatrist. (For all of their individuality and anthropological acumen, both Suburbia and Out of the Blue carry the vestiges of the Fifties JD movie.)

Out of the Blue played BAMcinématek last month as part of a 12-film series titled “Punk Rock Girls,” which opened with a preview screening of We Are the Best!, the rest of the slate including the likes of the Nancy Dowd–scripted Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains and Derek Jarman’s 1978 Jubilee, which features roles for formidable female punks like Siouxsie Sioux and all three of The Slits. Like Out of the Blue, which takes place on the shabby fringes of blue-collar Vancouver, these movies have desolate backdrops—a postapocalyptic Britain in Jubilee, a dead-end central Pennsylvania in Fabulous Stains. Cebe, however, doesn’t even enjoy the camaraderie of bandmates in her purgatory. She has girlfriends her own age, but have feathered hair and dress to fit in. You wonder if Cebe’s ever actually met a punker, or if the idea of punk rock is just something that floated to her over the radio waves from the outside world, something that she seized on and embellished what little she knew of—Johnny Rotten, safety pins—with her own imagination. (She mostly seems to listen to Elvis and Neil Young, whose 1979 “Hey Hey, My My” provides the film its title.) I can’t think of another film that so perfectly encapsulates how, in the absence of readily available older-sibling instruction or searchable and downloadable identity, kids left to forage for their own thing rummaged up very idiosyncratic and entirely bizarre handmade identities. When I was 14 years old, for example, I was regularly going to school in a polyester Goodwill blazer in plaid Easter colors accessorized with a three-foot length of industrial chain, worn entirely for cosmetic purposes, which made a tremendous clatter whenever I sat down in the classroom. I am certain that I looked literally insane, which is the risk you run when you make things up as you go along.

This would’ve been in 1994, not long after Kurt Cobain had quoted “Hey Hey, My My” in his suicide note. Turning away from a fucked home situation to cobble together an identity out of spare parts in a nowhere Northwest, Cebe might be Cobain’s female counterpart—she’s the right age to be his twin sister. Cebe never gets a shot at finding a creative outlet, however. The nearest she comes is on a runaway trip into the city, being invited to sit in behind the kit for Vancouver band The Pointed Sticks after their drummer takes her under his wing in an interaction that’s halfway between big-brother benevolent and predatory. (The bands plays “Out of Luck,” released via Stiff Records, and “Somebody’s Mom.”) To draw out the punk/Bresson comparison, this brief moment of release and glimpse at another, outside life is Cebe’s version of the bumper-car ride in Mouchette.

Another State of Mind

Before going onstage, the drummer is harassed by some kid with a camcorder asking “What does punk rock mean to you?”, probably a film-school dropout taping shows. A handful of embedded documentary reportages on punk, asking essentially that question, were in fact completed, including the abovementioned Decline of Western Civilization, and Adam Small and Peter Stuart’s Another State of Mind. (Rumors of Decline coming to DVD remain exactly that, as it’s apparently snared in a Gordian knot of rights issues, while Another State is on disc, and can be watched in its entirety on YouTube.) Small and Stuart’s film follows Youth Brigade and Social Distortion on a monthlong, cross-country tour over summer 1982 in a customized school bus, including a visit to Ian MacKaye, Minor Threat, and the Dischord House in Washington, D.C. The tour is the brainchild of blowhard Youth Brigade frontman Shawn Stern, organized under the auspices of the Better Youth Organization (BYO), intended to proselytize for punk positivity, but road life shows the Los Angelinos a grimmer and stranger reality. It’s a film of characters glanced who appear for only a scene, but stay in the memory for a lifetime, and if you’re looking for an antidote to We Are the Best! and its positivity, look no further than Marcel, Manon, and the grim, grim scene in Montreal. (As for the co-directors, I’m not sure what Stuart has been up to, but Adam Small recently a story credit on another great American road movie, 2013’s Jackass Presents: Bad Grandpa.)

In the last decade or so, however, the dearth of documentaries that were there to witness this particular chapter of history has been more than overcompensated for by those that have popped up to enshrine it. There’s been a bumper crop of rock docs, safe-bet low-overhead movies that, by catering to an inscribed fanbase, practically guarantee that they’ll break even, punk subjects having proved particularly popular. These movies, almost without exception, are completely extraneous—why would anyone waste years of their lives on a live-action MOJO article?—but they’re nice to drift off to, and I go through them like Pocky. Last weekend I caught up with Sini Anderson’s 2013 documentary The Punk Singer, about Bikini Kill and Le Tigre frontwoman Kathleen Hanna, recounting her career and premature retirement to address medical complications relating to Lyme disease.

Cobain is one of the players in Anderson’s movie—Hanna spray-painted “Kurt Smells Like Teen Spirit” on Cobain’s wall, and so gave a title to his band’s breakthrough hit. He also apparently warrants a chapter in a new tome called Twee: The Gentle Revolution in Music, Books, Television, Fashion, and Film by Marc Spitz, whose previous credits include co-authoring We Got the Neutron Bomb: The Untold Story of L.A. Punk with Brendan Mullen. I haven’t read Spitz’s book, but I did read a review of it by Judy Berman in Flavorwire which wonders why riot grrrl is “relegated to a few accusatory footnotes” in Spitz’s history. It should receive more attention—but not, as Berman suggests, because of affinity. Riot grrrl’s abstemious, finger-wagging, purer-than-pure attitudes created a Lord of the Flies contest to see who’d get the conch and be allowed speak for the scene, and this sent defectors to apolitical Twee in droves. In this respect, riot grrrl was the XX chromosome mirror image of PC, radicalized hardcore/punk, where zines like the Tim Yohannon–edited Maximum Rock n’ Roll and HeartattaCk were attempting to dictate and police a party line. In this case, the pushback came from punk-identified music that took high dudgeon at the surplus of high dudgeon, self-consciously unimportant pop-punk like Screeching Weasel’s “Nicaragua” (“I don’t give a fuck about Nicaragua… I don’t care about suburban white kids/ Trying to show they’ve got compassion/ Politics are boring/ Your politics are fucking boring…”) or, more articulately, Jawbreaker’s one-two of “Indictment” and “Boxcar” (“It means nothing, selling kids to other kids…”). I think about the punctilious correctness and snitchy, gossipy callout culture that flourished in both riot grrrl and hardcore frequently, as I see it every day, on a far grander scale, in the outrage economy of the Internet.

In both riot grrrl and “evolved” hardcore there was a distinct element of liberal-arts enlightenment arriving to castigate what, in its ‘80s incarnation, was a phenomenon largely aligned with the working class. A challenge to that homosocial status quo, however, was overdue to come from somewhere. “You can get hurt, you can, if you’re a girl,” says one female interviewee in a section of Another State of Mind devoted to slam-dancing, concluding: “From a girl’s point of view, I don’t think that slamming’s advisable. I think it’s pretty stupid, but it’s a good way to get your aggressions out for a guy.”

This is yet another issue that never arises in We Are the Best!, while figures like Hanna and MacKaye actively opposed the tendency for bully-boys to dominate the pit and the scene. The history of scenes in general is defined by opposing impulses of inclusivity and exclusivity: Being open to anyone who would like to be involved, yet setting up standards of behavior and cred checkpoints to keep out the phonies. If card-carrying subculture membership, as We Are the Best! would have it, is a means to create a feeling of specialness through a shared secret, then the power is dispelled when the secret becomes everyone’s property.

Heavy Metal in Baghdad

There’s no great threat of this in 1982, as Bobo and Klara’s classmates take pleasure in taunting them with the news that “Punk is dead,” a claim made often enough to warrant investigation. The Silver Jews’ “Tennessee” begins with David Berman crooning “Punk rock died when the first kid said / ‘Punk’s not dead, punk’s not dead!’” which by my reckoning means a crib death. If, however, we’re talking about a particular style of small-band music with identifiable traits, no different than rumba or honky-tonk, punk will be alive as long as there are a significant number of people interested in playing and listening to it. If, instead, we are talking about a culture defined by opposition, negation, and the creation of an alternative economy, things become rather trickier. For starters, it’s harder and harder to épater le indigenous bourgeois these days, so Western audiences have been responsive to narratives that find the front lines of the subculture wars abroad, in documentaries like Heavy Metal in Baghdad (2007), No One Knows About Persian Cats (2009), and Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer (2013), which raise the stakes that Brody finds so appallingly low in We Are the Best!.

As every generation gets the punk it deserves, so every period picture is about two periods, the one it depicts and the one it was made in. In looking at We Are the Best! and the responses it has evoked, then, it’s worth asking what this says about the popular perception of punk in 2014, as well as 1982. In part, the movie supplies a contemporary demand for affirmation by way of Strong Female Characters, the desired “culture of praise” spoken of in The Punk Singer, here playing out in a three-person nucleus of mutual support, today institutionalized in girl-power rock camps. (I seem to recall Kim Deal having a hearty laugh at that last phenomenon on a radio interview.) I believe this is what Brody is objecting to in part, much as he objected to Manohla Dargis once suggesting that the Film Society of Lincoln Center foster “cinematic culture by means of educational programs,” in his piece earlier this year called “Keep the Movies Unschooled.”

The subhed of the Guardian review quoted earlier states that We Are the Best! “will appeal to anyone who has ever been a teenager”—which is odd, considering that a relatively small fraction of people have experienced as teenagers anything like what the girls in WAtB! do, and in fact are more likely to have picked on someone like them than gone out-of-step themselves. The once-crucial cred checkpoints that I referred to above have, however, been bypassed and invalidated by life online, which reduces the risk of leading with one’s chin into hostile terrain (record store, VFW hall, pit). Consequently, the once-exclusive cabals of punk and hardcore have become public property—consider the universal indignity that greeted the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Punk: Chaos to Couture” show last year. “It’s not about the clothes,” we all cried as one. “It’s about the spirit!” When, as reported earlier this year in the PBS Frontline documentary “Generation Like,” the phrase “sell-out” has literally ceased to have any meaning to contemporary youth culture, we need a reassuring touchstone for authenticity. Punk is that touchstone.

I’m sympathetic to many aspects of We Are the Best!—the ensemble cast is a small miracle—but even with the best of intentions, it utlimately participates in the ongoing, backward-looking fetishization of yesterday’s tropes of DIY authenticity. At absolute worst, this means re-enactments of the teenaged basement-show experience for LARPing twentysomethings who lacked the intrepidity to experience it the first time around, and photoshopped cut-and-paste flyers for nonentity hype-zeppelins like Perfect Pussy. When it’s sorely necessary to revise time-tested Us Vs. Them dichotomies to apply to a Brave New World that has a shape-shifting Them, there’s no more craven opt-out than saying I Like That Old-Time Punk Rock ’n’ Roll.