Representation + Belladonna of Sadness

Spending a lot of time with something—a film, a genre, a culture—doesn’t always guarantee a more profound understanding of it. The simplest things can be irresolute, refusing easy categorization or moral binaries. And because we live in a time when even very plain statements are judged not for their aesthetic value but solely by the “politics” they evince, Eiichi Yamamoto’s beautiful and obscene anime Belladonna of Sadness (73) requires such a disclaimer. Adapted from Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière (a history of witchcraft published in France in 1862, the same year as Les Misérables), it tells the story of a young peasant woman, Jeanne (voiced by Aiko Nagayama), who forms a pact with Satan, defies her despotic king through magic, heals commoners’ suffering from the black plague, and finally gets burned at the stake. The film is a piece of erotica wrapped in a flimsy proto-Marxist-feminist yarn—it closes with Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People and the absurd subtitle “…at the head of the Bastille stood the women”—and our protagonist never enjoys a single instance of truly consensual sex. Instead, there’s a lot of groping and wheedling pleas for more made by the devil (voiced by the legendary Tatsuya Nakadai), and plenty of expressionistic sexual violence, most unforgettably when Jeanne’s body is ripped in half while she’s being raped. These moments are harrowing and convey a sense of tension and violation but take on an entirely different meaning when considered alongside the endless shots of her bare breasts, torn clothing, and naked, lithe form.

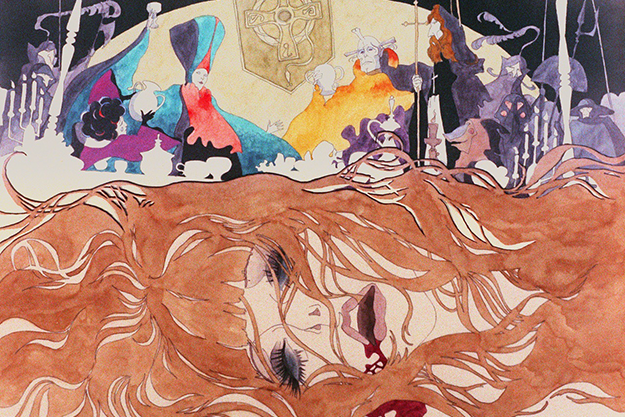

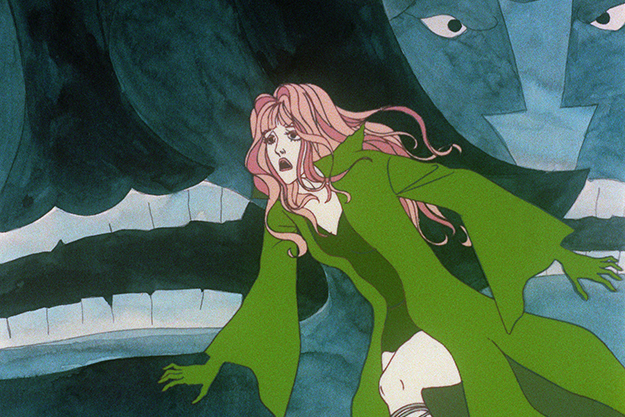

The line between sadistic pleasure and sympathy is ambiguous (though certainly weighted toward the exploitative), but it’s not the only conflicting aspect of the film. Produced by Osamu Tezuka’s then-nearly-bankrupt Mushi Production, Belladonna of Sadness features animation that alternates between astoundingly gorgeous compositions, overtly experimental, outrageously of-the-time groovy flights of fancy, and lento pans over still drawings, à la the incredibly low-budget 1966 Thor TV show. Aside from having saved money, these drawings—each hand-painted by Kuni Fukai—help to offer dramatic pauses or ruptures in the narrative that feel tangibly different from the sections with animated movements. They also emphasize the radical difference in how the characters are drawn: Jeanne, long-legged and sylphlike, looks nothing like her fellow peasants, who are short and round and drawn in a children’s-book style with red circles on their cheeks; meanwhile, the members of the royal court look more like Jeanne, tall and more detailed, with gothic and alien elements (the regent who so cruelly exerts his droit du seigneur and rapes Jeanne on her wedding night has a hollow, skull-like face and two bones sticking through the middle of his cranium). At important moments in her “transformation” from victim to queen of enchantment, Jeanne is rendered in a style resembling the lush, swooping Art Nouveau lines of Aubrey Beardsley; at others, her face is drawn in a sketched, lifelike fashion that appears nowhere else in the film, where detail signifies a form of intensified emotion. Likewise, even before her satanic pact, Jeanne’s hair cycles through a variety of colors (purple, brown, blonde, charcoal, to name a few), five years before punk broke.

These unnatural shades are typical of the manga/anime tradition, as are the large eyes (“filled with dreams,” per an old manga artist’s manual) and milky white skin. Given that this story is set in France, it makes sense that the characters have European features; in other manga and anime explicitly set in Japan (or with characters who have Japanese names), the motivations behind these phenotypic choices, and how they should be read, are far murkier. Last week, the hashtag “#notyoursidekick” gave voice to the outrage surrounding the casting of Tilda Swinton as The Ancient One in the forthcoming Doctor Strange movie and Scarlett Johansson as Makoto Kusanagi in the Ghost in the Shell adaptation, as well as a larger dissatisfaction with the invisibility of Asian characters in Hollywood films. Both properties are based on comics that overtly dealt with the existential, but they come from vastly different traditions: the former drawn by Steve Ditko, a hardcore objectivist and Marvel artist (who was for many years denied credit for his creations by Stan Lee), the latter by Masamune Shirow, a cyberpunk and mecha aficionado with no stated conservative political leanings. Ditko has long advocated obscuring a hero’s facial features with a mask so that the reader could project him or herself onto the character—a type of identification that has less to do with identity and more to do with something more innate in human nature. Though I’m loathe to wade too far into the potential Freudian or tribal waters Ditko’s approach implies, it touches upon how crucial visual parity is in comics and animation: “simple” or “cartoony” drawings function as the equivalent of short, carefully constructed sentences intended to express meaning efficiently, not indicate an intended audience. (It’s like a sentence analysis that claims Hemingway wrote at a fourth-grade level—if you’re counting sentences and not taking into consideration content, of course he did.)

This leads back to Tezuka, another comic-book master who drew in an overtly barebones, simplistic style but aimed to drive the form forward with ventures like Mushi Production. Frequently compared to Walt Disney in terms of cultural import in Japan, Tezuka drew hundreds of volumes of manga over his prolific career, several of which were turned into animated series, such as Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion. (To complete the circle, some aficionados argue that Disney’s The Lion King ripped off shots from the Kimba series, which was dubbed into English and syndicated in the U.S. for a time.) On his pages, Tezuka pushed the envelope formally with inventive panel layouts and deeply strange stories and characters: the eponymous surgeon’s assistant in Black Jack, who appears to be a small girl and is alternately referred to as his wife and daughter, is actually a sentient teratoma that he removed from one of his patients; a sympathetic character in Ode to Kirihito dies after being breaded and fried in a circus act gone awry; Message to Adolf is replete with slapsticky cliffhangers and doesn’t reflect Japan’s complicated relationship to Nazi Germany in any respect.

Listing these idiosyncrasies isn’t to reinforce the stereotype of “wacky crazy Japanese stuff”—that’d be infantilizing, reductive, and orientalist—but rather to characterize the elastic creativity that Tezuka was invested in: truly nothing was off limits in his oeuvre. Belladonna of Sadness, along with the other two titles in Mushi’s explicit “Animerama” series, A Thousand and One Nights (69) and Cleopatra (70), were also responding to the emergence of “pink films,” formally daring softcore works that were an outgrowth of the various late-’60s waves. Because they were animated, the films in the Animerama trilogy (all directed by Yamamoto) had more leeway in terms of representation than their live-action counterparts. Pink films don’t depict intercourse, and during the genre’s early years, never showed nipples or even full views of naked bodies, a result of postwar censorship laws and prewar social mores. (To offer a sense of how conservative the latter were, the first on-screen kiss between two Japanese actors didn’t occur until 1946’s Hatachi no seishun, and even then the actress put cellophane between her lips and her co-star’s.) Contrast this with the smorgasbord of flesh in Belladonna of Sadness, which at one point includes a surreal village-wide orgy coordinated by Jeanne’s magic. In this context, the film can be understood as part of a larger artistic/political movement that challenged societal convention.

Of course, as was true with many instances of the sexual revolution on-screen in the U.S., these confrontations were clearly at the expense of women. Yet the visual experience of Belladonna of Sadness is truly unique, with watercolor textures and techniques that simply don’t appear in narrative animated films. Carefully constructed and a little sloppy, alluring and disturbing, this gem deserves a trigger warning, but also a chance.