Beautiful Work: The Female Gaze in Beau Travail, La France, and The Romance of Astrea and Celadon

Beau Travail

There is no great mystery as to why the role of cinematographer was, until the past few decades, almost entirely closed to women. Men have long cherished the idea that women are incapable of handling machinery or understanding anything scientific, and the cameraman’s job is thought of as both technical and rather swashbuckling—it is called “shooting,” after all, as though the image were big game. Challenging these assumptions, “The Female Gaze,” a series running at the Film Society of Lincoln Center from July 26 to August 9, brings together 36 films with female cinematographers. The earliest is Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1976), lensed by Babette Mangolte, and approximately half of the titles are French productions or co-productions. Why the film industry in France seems to have made room for women behind the camera earlier than others is one intriguing question raised by this lineup. Two more, prompted by the title and framing of the series, are whether having a woman cinematographer makes any difference to what winds up on screen, and whether—a slightly different question—it makes sense to speak in terms of a “female gaze.”

To dispose of the first question: there is, of course, just as much variety in the work of female cinematographers as of male, and even within the styles of individual camerawomen. Agnès Godard, for example, is represented by two of her radically different collaborations with director Claire Denis. The look of Beau Travail (1999) is hard, full of sharp contrasts between extreme close-ups and long shots, stillness and rapid action, dark and painfully bright scenes; while the exquisite 35 Shots of Rum (2008) observes faces, domestic spaces, and routines of family life with hushed tenderness, and brings the same blend of sensuality and cool precision to trains hurtling along steel rails, rainy winter streets, and even a blood-soaked body on the subway tracks.

Films in the series do, however, provide a welcome opportunity to shake off stale notions of cinema as dominated by the “male gaze.” This argument—expounded most influentially by Laura Mulvey in her 1975 article “Visual Pleasure and the Narrative Cinema”—presupposes not just that films are largely made by men but that they assume the viewer to be male, catering exclusively to his pleasures, and that they invariably present the active protagonist as male, with women serving only as passive, objectified erotic spectacles. This reading, to anyone broadly versed in film history, feels willfully blinkered. The development of Hollywood’s narrative cinema was heavily shaped by men like producer Irving Thalberg, who firmly believed that women were the core audience for movies, and that it was commercially imperative to appeal to their tastes—for instance, with movies built around female protagonists (the existence of which Mulvey briefly acknowledges but declines to discuss). These movies created roles for actresses like Barbara Stanwyck, who on screen wielded a gaze as bold and dominating as any in cinema; the way she looks men up and down, subjecting them to open and merciless appraisal, reduces her male co-stars to blushing prey or deflated rejects.

La France

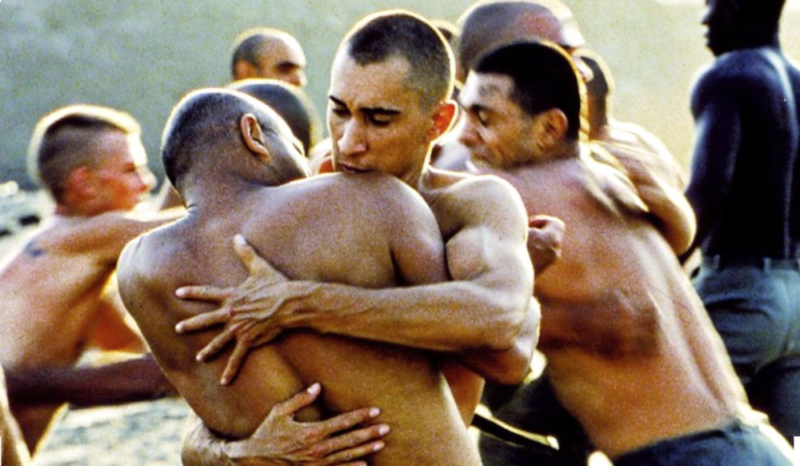

Mulvey may assert that “according to the principles of the ruling ideology and the psychical structure that back it up, the male figure cannot bear the burden of sexual objectification,” but Hollywood was always an equal-opportunity exploiter of sex appeal. In the 1920s, Rudolph Valentino taught the studios that female audiences would flock to see a man presented as an overtly erotic fantasy object, and from then on actors possessed of fine physiques—even paragons of masculine reticence like Joel McCrea—may as well have had clauses in their contracts requiring them to bare their chests at least once in every movie. A paradox has always existed: that the films most exclusively embedded in masculine realms such as war, action-adventure, sports, and the Western frontier, are also the most attentive to the aesthetic enjoyment of men’s bodies. This is certainly the case in the hypnotic Beau Travail, a loose adaptation of Herman Melville’s Billy Budd with the setting transported from a naval ship to a French Foreign Legion encampment in the bleached, dazzling plains of Djibouti. The most striking and memorable scenes in the film record the soldiers performing ritualistic, dance-like exercises in the desert, their shaved heads and naked torsos sculpted by the fierce sun, their movements arrestingly graceful and cryptic. Denis explained that these were authentic routines introduced by a member of the cast who had served in the Foreign Legion, and that it was only afterward, when paired with music (the score incorporates excerpts from Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd), that the choreographic quality became evident. Framed by opening and closing scenes in West African discos, the film is one of the most provocative and mysterious cinematic meditations on dancing as communal ritual and as self-expression.

As Hannah McGill pointed out in an excellent essay for the BFI, the fact that most readings of the film assume that its aesthetic and narrative focus is homoeroticism—that it is repressed desire that causes Chief Adjutant Galoup (Denis Lavant) to conceive a murderous hatred of the handsome and popular soldier Gilles Sentain (Grégoire Colin)—seems proof of how far the concept of a female gaze was from anyone’s mind. But this is a film about men seen through the eyes of women—director/co-writer Denis, her regular cinematographer Agnès Godard, and editor Nelly Quettier, and it doesn’t just observe and celebrate male bodies, it probes, sharply but compassionately, the dynamics of all-male groups, particularly the cankers of jealousy, competitiveness, and insecurity. Galoup is a small and ugly man, but clearly vain about his athleticism, deeply self-conscious, and fixated on being the perfect legionnaire. Sentain has all the ease and openness he lacks, and Galoup bitterly envies his charisma, particularly afraid of being displaced in the regard of his superior officer, the gently cynical Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor, reprising his role from Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 Le Petit Soldat). The camera spends far more time watching the tense, sullen Galoup, who narrates the film in a rueful voiceover, than it does admiring Sentain. It is significant that Beau Travail was originally inspired by a commission to make a television film on the theme of foreignness. Its overwhelming mood is one not of overheated desire but of regret and loneliness, the sadness of someone who seems like an exile wherever he goes.

La France (2007), directed by Serge Bozon with cinematography by his sister Céline Bozon, offers an even more idiosyncratic and stylized treatment of war and the military unit. The setting is World War I, but the fighting is never on screen. From the opening shot of women running down a green hill, which they had climbed in the futile hope of glimpsing the front and their absent men, this is a movie about how war is internalized, how it haunts and changes people. The story centers on one of the bereft women, Camille (Sylvie Testud), who receives a disturbing letter from her husband in which he curtly severs their ties. Her response is to set out in search of him, disguised as a boy; the Shakespearean echoes of this premise are amplified by the way that she wanders into the woods and there finds a community existing in mysterious, spellbound isolation. It is a regiment of soldiers, who reluctantly allow Camille to tag along with them; the riddle of what they are actually doing so far from the front and why they never seem to engage in any typical military activities is answered, in the film’s second half, with a revelation that instantly makes sense and deepens the drama. La France is filled with cinematic allusions, but remains almost wholly free of the usual movie clichés of army life. These soldiers don’t grouse about food or talk about women, they sit around reading poetry (they share a collective obsession with the mythical submerged island of Atlantis) and playing music. While soldiers singing together is nothing unusual, the musical sequences here are strikingly strange: when the men take out their quaintly handmade instruments, they launch into songs (written for the movie by Fugu and Benjamin Esdraffo, with lyrics by the director) in the jaunty mode of 1960s Sunshine Pop, which are not only jarringly anachronistic but out of key with the melancholy, somber mood of the film.

The Romance of Astrea and Celadon

The songs’ cryptic lyrics are written in the voice of a woman addressing an absent lover, as though the men were ventriloquizing Camille’s yearning. For a large part of the story, her gender fades into the background, as she gradually becomes absorbed into this intimate group. When they do eventually learn the truth, they seem neither surprised nor troubled by it. She is an ambiguous character, by turns helpless and brave, single-minded and adrift, a nurturing woman and a lost boy. For all its dreamlike stylization, the film’s greatest strength lies in the deep, aching emotion it summons by the end. These men, and particularly their stalwart lieutenant (Pascal Greggory, who brings a tremendous weight of authority and contained grief to the role), carry a burden of guilt and loss, but they also embody the survival of kindness and of loyalty to an ideal, making their weirdly cheerful songs poignant.

As much as by music, the film is defined by the expressiveness of its landscapes: lush green forests under gray skies and mist or nocturnal half-light; rugged, sinister cliffs and caves out of a Courbet painting; the charred, muddy wasteland of the battlefield, where you expect the men to join the fight, only for them to build a raft and drift down a murky river. The Bozons devised a distinctive look for the film, a subtly soft, uncanny “aquarium lighting,” as the director described it. The results, blending plein-air naturalism with dramatic atmosphere, seem deeply and uniquely French. A poetic vision of the Gallic countryside also pervades Éric Rohmer’s final film, The Romance of Astrea and Celadon (2007), with cinematography by his frequent collaborator Diane Baratier. This too is a film that plays fast and loose with historical eras: it is based on a 17th-century five-volume novel by Honoré d’Urfé, itself set in an idealized, pastoral imagining of 5th-century Druidic Gaul. The movie is a daringly straightforward translation of an archaic work, complete with lengthy metaphysical debates about the nature of love and the essential monotheism of Druidic religion, and at the same time a jeu d’esprit that gathers a number of extremely good-looking young people, dresses them in fetching, vaguely Grecian garb, and turns them loose to frolic in the verdant, sun-dappled, breeze-stirred meadows and woodlands of the Auvergne.

The titular lovers are a shepherd and shepherdess seemingly without any sheep to tend, giving them all the more time to devote to affairs of the heart. When Astrea (Stéphanie Crayencour) mistakenly believes that Celadon (Andy Gillet) has betrayed her, she banishes him from her sight, and he promptly throws himself into the river. This launches him on a strange, ethereal odyssey in which he is rescued by a band of “nymphs” (the rulers of an apparently matriarchal society), becomes a forest hermit, and finally dresses as a woman in order to be near his beloved without breaking her injunction that he never appear before her again. Gender reversal runs rampant. The androgynously beautiful Celadon is an object of desire for almost every woman in the film, and first dons drag in order to escape from the imperious advances of his rescuer Galathée (Véronique Reymond). “Dieu, qu’il est beau!” (“God, he’s handsome!”) she sighs, fondling him as he lies unconscious. Even awake, Celadon remains a stubbornly passive hero. Resisting all those who try to convince him to go back and reason with Astrea, who has discovered his fidelity but believes him to be dead, he insists that he cannot defy her ruling; because he loves her he says, “How can I not love to obey her?”

Gender-switching disguises have always been a way to introduce a frisson of the forbidden into romantic dramas. While men in drag are usually played for comedy, Gillet makes an uncommonly persuasive woman, and the film’s final scenes present a vision of beauty, love, and even sex transcending gender; it hardly seems to matter whether he is male or female. Putting on Astrea’s dress, Celadon acts out the argument made in an earlier scene, that the true lover becomes his beloved. In this ravishing work, notions of a “male gaze” or a “female gaze” seem beside the point, and the argument of theorists like Mulvey that cinema’s “voyeuristic” or “scopophilic” qualities are inherently oppressive and exploitative seems perversely joyless. Viewers of any persuasion are liable to feel like Celadon, drinking in the sight of the sleeping Astrea and “wishing that, like Argus, he had eyes all over his body.”

Imogen Sara Smith is the author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City and Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy, and has written for The Criterion Collection and elsewhere.