Queer & Now & Then: 1996

In this biweekly column, I look back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface. Read the introductory essay.

It’s very clearly faked, but the rainbow that proudly arcs over the sky in the shot behind the opening title card of Beautiful Thing resonates as one of the most encouraging movie images of the 1990s. Any viewers who saw British director Hettie Macdonald’s tender yet gratifyingly rough-edged coming-out film upon its release, or perhaps saw it at a fragile age in their lives, are unlikely to have forgotten its four vividly drawn central characters—not just pubescent boys Jamie and Ste, who gradually reveal their attraction to one another, but the two women who satellite them, Jamie’s mother Sandra, and their neighbor Leah, an older teenager obsessed with Mama Cass. But even more vivid in the memory is the extraordinary sense of place fostered in the film, the social and geographical specificity of the location, most of it set in and around a Brutalist concrete postwar flat in South East London.

Queerness does not exist in a vacuum; the tenor, range, and limitations of an individual’s queerness and the variable responses from those surrounding that individual are due to a compendium of social factors, chief among them race and class. It’s one reason why films like Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight or Andrew Ahn’s Spa Night are such lived-in depictions of gay youth, and also why Beautiful Thing stands apart in its own way. In a tradition ranging from the kitchen-sink realist films of the late ’50s and early ’60s to the contemporary works of Mike Leigh and Andrea Arnold, English movies set among the working classes have tended to have fatalistic trajectories and miserabilist aesthetics, underlining their drabness to reflect their characters’ sense of hopelessness and to visually convey a lack of upward mobility. But there’s that rainbow in Beautiful Thing, and it’s unmistakable. Years before the “It Gets Better” movement, Macdonald’s film hinted at a bright future in the most cinematically improbable of places.

The odd-duckness of a working-class gay love story with a happy ending was not lost on Beautiful Thing’s writer, Jonathan Harvey, who adapted his own play for the screen. Harvey, who grew up in a concrete, low-income housing estate in Liverpool, felt like he had never seen his own experience on screen or stage. He said in an interview at the time, “If you were a working-class gay person on TV, you would be kicked out by your dad and became a rent boy. If you were middle-class then perhaps you got AIDS and died.” Young Jamie and Ste, played with low-key likability and aching sensitivity by Glen Berry and Scott Neal, aren’t wrenched apart, neither of them dies, and the film doesn’t end in tears.

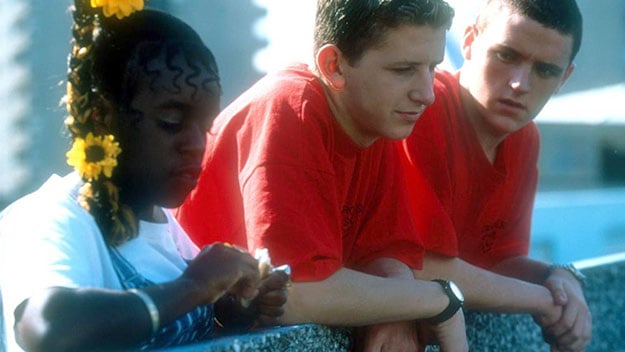

It can be strenuous working against artistic expectation and social convention alike, and the positivity of Beautiful Thing is appropriately hard-won for all the characters. Produced for Britain’s Channel Four before becoming an international theatrical hit, Macdonald’s screen version—her film debut after directing the play as well—is a mostly naturalistic affair, punctuated by bright spots of color (the boys’ blazing red school sweaters, the sky-blue-painted doors of the flats) and, most memorably, song: Leah’s intense love for The Mamas & the Papas provides an excuse for a recurring soundtrack of the late-’60s American band’s music, a peppy contrast to the characters’ daily existence, which is often marked by conflict and abuse (the prior year’s queer-ish Muriel’s Wedding had similarly used the music of up-tempo ABBA to mitigate its plot’s often unremittingly bleak turns). Here, songs such as “Creeque Alley” and “Make Your Own Kind of Music” feel less like emotional escapes for the audience than reminders that the characters exist on their own particular wavelengths and set their own rhythms. And because the choice of music is connected to the fierce individuality of the film’s one main black character, Leah, played by British actress Tameka Empson (now known for her role on the popular series EastEnders), an added element of outsiderness is granted to music that is otherwise fairly standard pop. Leah’s character is perhaps the hardest to pin down—supportive one minute, rude the next; a confidante or a seeming betrayer—and Empson’s performance is therefore the most fascinatingly mercurial. (Empson, Berry, and Neal all studied acting together at the Anna Scher Theatre School, which helps explain the ease with which the young actors all perform.)

For reasons not completely clear and which are hard to dissociate from simple, entrenched racial bias, Sandra (Linda Henry) is often depicted as Leah’s adversary, verbally hounding and at one alarming point physically attacking the teenage girl for perceived rumor-mongering about the older woman’s younger boyfriend, their respective actions indicating that the denizens of this tightly squeezed apartment complex form an unlikely and sometimes unwanted family. A single parent out of work, Sandra is understandably beleaguered, given to violent mood swings in her relationship with her son, one moment descending into a slap-fight, the next showing tender, tearful concern. Because of this, there’s an inherent tension laying over the film about how she’ll react when she finds out that there’s been a love developing between Jamie and Ste, whom Sandra had taken in one night after he had a violent encounter with his perpetually soused father and drug-dealing older brother. Sandra’s decision to let him sleep over in Jamie’s bedroom all but initiates a love connection.

It’s in these intimate bedroom scenes between the two boys that one can best appreciate Hettie Macdonald’s attentive, patient direction. She never overplays the longing Jamie and Ste have for one another, showing that it grows naturally out of both biological urges and circumstances of proximity. They bond over a shared sadness, finding solace in one another’s company and in the clear reassurance each feels for having found a sensitive kindred soul. First contact comes when Jamie offers to rub lotion on the bruises dotting Ste’s back after another pummeling from his brother. Following this delicate, affectionate touch, Ste refuses to turn over on his back, claiming he’s too sore but clearly hiding an unexpected hormonal excitement—it’s a moment that likely would have been either overdramatized or made forthrightly comical in other hands, though Macdonald gently brushes by it, just one of many daily potential humiliations teenagers have to navigate as they slowly come to understand their ever–evolving bodies.

Macdonald is one of a handful of filmmakers to have been at the helm of a landmark gay film without ever making another openly queer movie (some of us are curious about whether Barry Jenkins and Sean Baker will be added to that list). Though as early as 1996 she was reportedly at work on a film adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Price of Salt, later adapted by Todd Haynes into 2015’s Carol, Macdonald has worked exclusively in television ever since, and has been back in view lately for directing the acclaimed new miniseries adaptation of Howards End, scripted by Kenneth Lonergan. Beautiful Thing thus remains a curious theatrical one-off, and though it’s among the more gentle entries in the queer canon, its impact on gay viewers who came of age in the 1990s is surely vast: it was the main feature in the Legacy section of last year’s NewFest, and it’s rare that I’ve spoken about it to someone who hasn’t broken out into a smile at the mention of its title.

Macdonald’s film may not wish to bust up the world like an Araki or Jarman film, but it is a reminder that joy itself, so long denied gay people on screen, is also an essential form of subversion. Beautiful Thing’s final act simply and lovingly revolves around a mission of togetherness: Jamie, Ste, Sandra, and Leah getting ready to go out for a night on the town. The boys can’t even wait to get to the gay bar, however, using the wide-open courtyard of the council estate as their dance floor, swaying to Mama Cass crooning “Dream a Little Dream of Me.” Sandra and Leah join as well, though in the spirit of inclusivity rather than attraction. Neighbors emerge from their flats to witness these pas de deux, the world watching as they hold close to one another. Summer sunlight flares into the lens as the camera gently rotates around the boys’ close, clenched embrace. It’s an unashamed public exhibition so powerful it became the film’s poster and most lasting image, an indication of how even the sweetest gesture of love can be poignantly political, and how the rules of queer desire are inextricable from time and place.

Michael Koresky is the Director of Editorial and Creative Strategy at Film Society of Lincoln Center; the co-founder and co-editor of Reverse Shot; a frequent contributor to the Criterion Collection; and the author of the book Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press.