Art of the Real: Andrea Tonacci

Bang Bang

“It was about revolt, rage and impotence.” That is how Andrea Tonacci, a key filmmaker in Brazil’s Marginal Cinema movement of the 1970s, once described his early work. Unlike Cinema Novo, which put Brazil on the international map in the 1960s by extolling its rural music and storytelling traditions (with folk figures such as the cangaceiros, or rural bandits), Cinema Marginal was a predominantly urban movement. It shared with Cinema Novo the general poverty of means, but it did not aspire to forge a national ethos. In this sense, Cinema Marginal was more a reaction “against”—against standardization of culture and political and artistic stagnation—than it was “for” anything.

Directors as diverse as Júlio Bressane, Rogério Sganzerla, Luiz Rosemberg Filho, and Ozualdo R. Candeias were also among its figures. Some filmmakers and critics came to question, and even resent, the “marginal” label. Yet the term aptly captures the movement’s willfully anti-establishment posture, as well as its marginalization, which was partly due to censorship. With commercial cinemas reserved for popular offerings, Cinema Novo and pornochanchadas (softcore porn), Cinema Marginal went udigrudi (underground).

Within that small, eclectic scene Tonacci was an important player. Born in Italy and educated in Brazil, with a focus on architecture and engineering, Tonacci never studied cinema formally. In an interview with the Brazilian film journal, Contracampo, he recalled instead growing up in São Paulo’s Centro, where the city’s cinémathèque used to be, and immersing himself in its programming. “I even watched film I wasn’t allowed to. I saw it all, Polish, Japanese, German, Indian cinema. For me, it was about discovery and revelation. I had no critical distance, so I got emotionally sucked in, and identified strongly with the films.”

Bang Bang

The thrill of discovery never abandoned Tonacci, who passed away in December from cancer. His quantitatively small yet stylistically immense legacy includes one of Brazil’s most startling avant-garde films, Bang Bang (1971), or Bangue Bangue, Portuguese slang for spaghetti Westerns. A tabloid story about three bandits and an inept policeman served as an inspiration. Out of this premise Tonacci wove a grotesque, tongue-in-cheek farce that, while retaining some suspense elements, consistently breaks genre conventions, and in effect frustrates audience expectations.

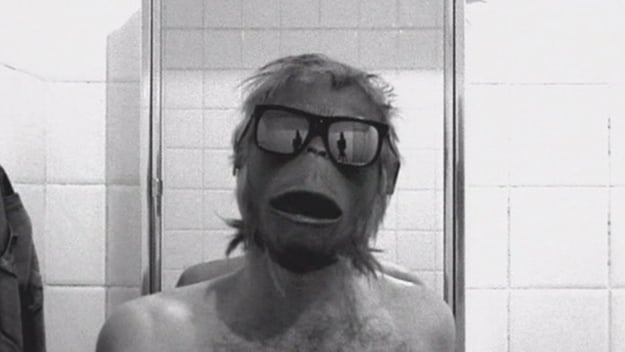

The film opens with an unnamed protagonist, played by Paulo César Peréio, hailing a cab, but then getting kicked out of it, after having a quarrel and a fistfight with the driver. The madcap sequence is the first hint that we must take the entire story with a grain of salt. In the next scene, three criminals ride a limo, and random gunshots ring out as the film’s title appears on screen. But as the camera zooms out, the swanky limo turns out to be a wreck, suspended on a high rig, in a giant auto-body shop—the tense moment turned into a cinematic gag. In a series of disjointed vignettes, our protagonist dresses in a monkey mask, makes love to a dispassionate young woman who in a subsequent scene dances flamenco on a city roof, runs into the three criminals in a lobby of a building, and is pursued by them later, in the countryside.

Throughout the film, Tonacci isn’t interested in plot denouement, narrative logic, or character development. The victim does not vanquish his pursuers; good does not trump evil. After a dramatic car crash, as one of the criminals sums up the plot, a crewmember on the film (presumably) throws a cake in his face—yet another meta-gag. Tonacci reminds us that we are participating in an act, or a joke, which he now and then unmasks before our eyes. Fittingly, Bang Bang’s final sound is a cackle.

Bang Bang

Tonacci once described his filmmaking approach in Contracampo: “Every time I come across something obvious, a clear meaning, I get rid of it. The question is always: ‘How can I make this symbol, this image, as ambiguous as possible, so that it takes multiple forms in a spectator’s mind?” In Bang Bang, Tonacci achieves this multiplicity by constantly drawing our attention to the artifice. The scene with the mask—the ape mask was inspired by The Planet of the Apes (1968)—confronts us with the reality of Peréio as an actor playing a role. In a bathroom mirror, we glimpse an image of the camera behind him, a reminder of our own role as spectators. The mask, a sign of mutability and a disguise, emerges as an essential human condition.

In his theatricality, Tonacci’s films retain some similarity to Cinema Novo, and to its key figure, Glauber Rocha. Rocha’s influence on Brazilian film was tremendous, and the success of Terra em Transe (1967) in Cannes and in Locarno, assured his place as the country’s leading public intellectual. In Rocha’s works, archetypal figures—cangaceiros, but also messianic priests and rebellious runaway slaves—pointed to Brazil’s colonial past. In Tonacci’s works, types became stereotypes. Stripped of archetypal quality, the three bandits in Bang Bang bear generic names: “Fat Man,” “Blind Man,” “Drag Queen.” In one scene, a mysterious magician makes the three criminals appear and then vanish with a snap of his fingers. Brazilian scholar Ismail Xavier, the author of the seminal text on Cinema Marginal, “Bang Bang: Passage, Not Destination,” has pointed out that the magician’s finger-snapping, which imitates montage, is a direct homage to early film pioneer Georges Méliès. The magician figure evokes cinema’s ability to conjure up fantastical scenarios.

In his brusque editing and his love-hate relationship with mass culture, Tonacci shares a deep affinity with the French New Wave, particularly Jean-Luc Godard. Bang Bang’s manic energy and bloody, jarring ending echoes the finales of Pierrot le Fou and Weekend, while its car chases are reminiscent of American film noir. Like Godard’s, Tonacci’s art is self-reflexive. When our protagonist meets a woman at a café, they argue over how to say “hello,” like two characters rehearsing a scene. Meanwhile, the three criminals approach the café and pose in the window. The frozen tableau mocks the idea of a heated pursuit. We see the film crew directly in the shot, and again, spontaneity turns to artifice.

Blah Blah Blah

Tonacci’s output came at a trying time in Brazil. The military coup of 1964 deposed the left-leaning president, João Goulart. The Institutional Act Number Five, AI-5, passed in 1968, further curtailed the rights of civilians, giving the government a free hand to persecute the opposition. While Rocha embodied the initial belief in a concentrated revolutionary response to the coup, with Terra em Transe as a transitional work, Tonacci’s short, Blah Blah Blah (1968), as well as Bang Bang, are products of a later, more cynical era. Blah Blah Blah opens with a politician (Paulo Gracindo, who appears as a poet in Terra em Transe), behind a microphone in a studio. A shadowy Orwellian figure, the politician clearly uses the media as his echo chamber. Tonacci overlays the politician’s call to order with videos of institutionalized violence. Reality splinters; the speaker’s version of events has no basis in life. The words “blah blah blah” in the voiceover undercut the righteousness of the discourse.

The two other speakers in the film are a radicalized left-wing worker and a representative of the disenchanted intellectual left. All characters are fictitious, but the text is archival: Tonacci culled the speeches from diverse historical records, from Arthur Miller to Brazilian general Castelo Branco to Adolf Hitler. The language, robbed of its original context, is thus a recycled mishmash. Like Rocha’s Terra em Transe, Tonacci’s short is permeated with profound disappointment, and offers no “way out.” If there is a positive element in both films, it’s the belief in art as a catalyst: art destroys old beliefs and forms, so that something new, yet undefined, may replace them.

The 1980s and ’90s marked a relative dry spell for Tonacci. He completed his third feature, Conversations in Maranhão (1983)—a result of the Guggenheim-grant research of native North and South American populations he undertook in the late ’70s. But it wasn’t until 2006 that he returned with the superb Hills of Disorder. He had conceived the original idea for the film some 20 years earlier, after hearing a story about Carapirú, a Native Brazilian from the Amazon tribe, Awá (Guajá), whose village had been devastated in the 1970s by local farmers. Carapirú, who believed himself to be the massacre’s only survivor, wandered the countryside for 10 years, before settling in a village in northeastern state of Bahia, some 2,000 kilometers from his native region. Carapirú integrated into the community, despite speaking no Portuguese. When the authorities aiding the Indian population finally found him, and hired a translator, Carapirú recognized in the youth his own son.

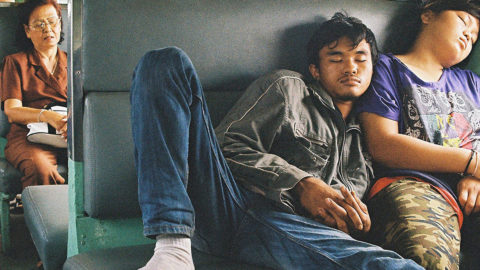

Hills of Disorder

The stirring tale had the makings of a fiction film, but Tonacci struggled to find an actor who could portray Carapirú. He finally cast Carapirú as himself, and had him relive his experiences. The result is a movie that stuns with its emotional acuity, and with the fluidity of its visual registers. The first 15 minutes ill prepare us for the shattering impact: we see Carapirú in the midst of his “family,” in what seems like a straightforward observational documentary, but is in fact a reenactment. Only when Tonacci cuts abruptly to the image of a hurtling train, which creates a sense of disorientation that will accompany Carapirú throughout as well as conveys the idea of a journey, do we begin to glimpse Tonacci’s multilayered, circular approach. Like a mind that constantly returns to the place and time of a traumatic event, the film circles around Carapirú’s past. What follows is a reenactment of Carapirú finding his village attacked and his loved ones slain, and then his solitary exile.

The action progresses simultaneously in the past and in the present. To signal the temporal switches, Tonacci intermixes black-and-white and color footage. At times, we catch a glimpse of the movie camera, a reminder that this is all a setup. Tonacci also inserts clips about the Amazon’s deforestation, culled from television news and from iconic films, such as the hybrid-docudrama, Iracema, Uma Transa Amazônica (1975), by Jorge Bodanzky and Orlando Senna, that decried the social ills and the economic plunder precipitated by the government-sponsored Trans-Amazon Highway. Eventually, Tonacci has Carapirú return to the Bahian village where he ended his journey. Here also two temporal modes unfold: in the present, Carapirú and the villagers look over old photographs and reminisce; in the reenacted scenes, which mirror Carapirú’s past, he is taken from the village and to Brasilia where he recovers his long-lost son. It is also here that a decision to return Carapirú to his origins is made. What follows is perhaps the most painful, indelible sign of change in Carapirú: he is shown returning to his native village, clad in city clothes, which set him apart. Profound ambiguity haunts the reencounter. Because Carapirú never communicates—Tonacci chose not to translate his Tupi-Guarani dialect—we can’t ever be sure if we should interpret the return as a source of solace, or pain, a paradise irredeemably lost.

For Tonacci, the film marked a crucial aesthetic and philosophical shift. He saw Hills of Disorder as an ethnographic work, in the sense of an “ethnography of the self,” a term coined by Brazilian film critic Jean Claude Bernardet. “I didn’t want to analyze Carapirú’s story,” Tonacci said. “It was a hook to present my story, my sentiments.” And yet, as much as the film is about Tonacci’s profound ressentiment of urbanity, and the disrespect he sees in the cities for both fellow men and nature, the more time passes the more Hills of Disorder reaffirms its status as an eerie portrait of one man: Carapirú. In Brazil, where the indigenous question is hotly discussed, as Indian lands continue to be seized illegally by farmers, and Indian territories are under threat from deforestation, its communities suffering poverty and violence, Tonacci’s docudrama has kept its currency as a major national event. Many documentaries about the plight of Native Brazilians have been made since; few have reached this film’s cathartic depths.

Hills of Disorder, Blah Blah Blah, and Bang Bang screen on May 1 as part of the Spotlight on Andrea Tonacci in Art of the Real at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Ela Bittencourt works as a critic and programmer in the U.S. and Brazil and is a member of the selection committee for It’s All True International Documentary Film Festival.