Tough Love: Alan Clarke

The Last Train through Harecastle Tunnel

Roughly from 1964 to 1990, the BBC’s drama department poured out a wealth of studio-recorded dramas and, increasingly, 16mm films that challenged the sociopolitical status quo. Sydney Newman, the visionary Canadian producer who ran the department for five years from early 1963 and introduced the groundbreaking The Wednesday Play anthology series, established a mandate of “agitational contemporaneity” that constituted “art in the service of the people.”

One of the fruits of this initiative was the visceral, anti-establishment filmmaking of Alan Clarke (1935-1990), who arrived at the corporation when he was 33 and directed 29 dramas there. It was television, yes, but it’s reasonable to speak of this output as “Clarke’s cinema”—for his angry egalitarianism and manipulations of film grammar were authorial. The BFI’s release earlier this month of “Dissent & Disruption: Alan Clarke at the BBC (1969-89)”—a home-video collection of the 23 stand-alone Clarke films still extant, plus the seven survivors of the ten 1967-68 dramas he made for the independent Rediffusion’s Half-Hour Story series—is likely to prove the British film event of 2016.

Until the 1982 advent of Channel 4 with its Film4 production wing, which accelerated the demise of videotaped studio productions predicted by Ken Loach’s part-16mm Up the Junction (65), British television drama was considered a writer’s medium, the domain of Dennis Potter, Jack Rosenthal, Troy Kennedy Martin, John Hopkins, David Mercer, David Storey, Trevor Griffiths, Alan Bleasdale, and Alan Plater, among others. The very titles of The Wednesday Play (64-70) and its successor Play for Today (70-84)—Clarke’s 60-odd works include two works for the first series, 11 for the second—and the ITV’s Armchair Theatre (56-74) emphasized their literary or dramaturgical properties over their filmic.

Penda’s Fen

This was misleading. Loach, Clarke, and colleagues like Mike Leigh, Stephen Frears, Roland Joffé, Michael Apted, and Richard Eyre were not passive interpreters of other people’s scripts—Leigh, in any case, wrote his own domestic tragicomedies. Loach shaped works he developed with such writers as Nell Dunn, Jeremy Sandford, and Jim Allen into a singularly humanistic socialist realist vision. Attentive to class divisions, manners, and behavioral nuances, Frears’s films of plays by Peter Prince, David Cook, David Hare, Stephen Poliakoff, and especially Alan Bennett were characterized by a visual economy and drollness, though Frears regards himself an auteur or stylist no more than do his champions.

What about Clarke? Sympathetic to social misfits and family casualties (as is Loach), youths especially, and antagonistic to patriarchal institutions (the Church, governments, the courts, prisons, schools, hospitals, multinationals), he was the telly auteur as roving anarchist—not an ideologue, however, but a director who approached the cinematic space representing Britain as a hectic ontological battleground.

Initially a stage director—of Beckett, Anouilh, O’Neill—Clarke first worked in television as an assistant studio floor manager. He emerged as a force in TV shortly after Kennedy Martin, Potter, and the Brechtian playwright John McGrath had liberated recorded dramas from the curse of the proscenium-arch—the conventional aesthetic that dominated naturalistic televised theater, and which smacked of upper- and middle-class elitism and complacency. The spring 1964 issue of the theater magazine Encore had published Kennedy Martin’s article “Nats Go Home,” a manifesto for a new form of non-naturalistic television drama that broke with the insistence on “subjective identification with characters” and sought “to free the camera from photographing dialogue, to free the structure from natural time and to exploit the total and absolute objectivity of the television camera.” Kennedy Martin argued that the TV dramatist’s priority should be capturing interior thought, an idea that became central to Potter’s fusing of what the mind sees and what he called the “alleged reality of the out-there.”

Baal

The non-naturalism imperative was a delayed sequel to the aesthetic austerity—in terms of acting, directing, dramaturgy, and design—that emerged in British theater as a direct result of the visit of Bertolt Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble to London two weeks after Brecht’s death in August 1956. The enthusiasm for Brechtian Verfremdung (the “alienation” or “estrangement” effect first described by Brecht in 1936) among such directors as Peter Brook, John Dexter, George Devine, William Gaskill, Peter Hall, and Tony Richardson saw “a style of self-conscious theatricality became prominent at the Royal Court, the National Theatre, and the Royal Shakespeare Company” (as scholar Art Borreca observed in the collection Brecht Unbound).

In 1961, James MacTaggart directed Jack Gerson’s Three Ring Circus for BBC Scotland, which McGrath described as the “ur-text” of British experimental television drama. It deployed long takes, modernist montages, and sound effects produced by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop to evoke, kaleidoscopically, the plight of an amnesiac in a European police state who assumes different identities to find out who he is. MacTaggart also produced the Kennedy Martin anthology series Storyboard (61), Studio 4 (64), and Teletale (64; which included Loach’s now lost debut, Catherine). The Glaswegian’s ability to attract armchair viewers to watch dramas that variously used narration, montages, fourth-wall breaking, and editing to music led to his appointment as the producer of the second series of The Wednesday Play.

Published alongside “Nats Go Home,” heavily influenced by the alienation effect, was an excerpt from Kennedy Martin and the Brechtian playwright McGrath’s script for their 1964 drama series Diary of a Young Man; Loach and Royal Court alumnus Peter Duguid each directed three of its six episodes. Another deconstruction of straightforward storytelling, the series strategically incorporated multiple scenes, montaged stills cut to music, and a bizarre voiceover narration, and made viewers aware of the camera, preventing subjective identification with the protagonists—two Northern lads looking for work and somewhere to live in London—but drawing attention to their struggles as working-class men on the loose in “the Big Smoke.” More attuned to the Marxist implications of Brechtianism than most of its theatrical champions, whose appropriation of it was markedly depoliticized, Kennedy Martin, McGrath, and MacTaggart created the conditions in which Loach and Clarke would thrive.

Stars of the Roller State Disco

Though the naturalist in Clarke was also influenced by Loach’s filming of Diary (partially), Up the Junction, and Cathy Come Home (66) on city streets, he would—as a Brecht obsessive directing Brecht’s first play Baal (82) for the BBC—opt for a full-blown Brechtian treatment (split screens, outdoors sequences shot on artificial sets, and David Bowie’s fourth-wall-breaking song performances); he also directed the little-seen Brechtian musical movie Billy the Kid and the Green-Baize Vampire (85). There are dabs and sometimes swathes of Brechtianism in many of his works, which refutes his sometime categorization as a social realist director. His films of David Leland’s Psy-Warriors (81) and Michael Hastings’ Stars of the Roller State Disco (84), which depict the training of military assassins and the plight of unemployed youths respectively, were videotaped on studio sets—a gleaming white prison-cum-torture chamber complex (with a pre-Guantanamo aura), a futuristic sleep-in roller disco—rendered as alternate realities. The rhythmic repetitiveness of each endows it with the quality of a never-ending nightmare.

In the hauntological masterpiece Clarke made of David Rudkin’s Penda’s Fen (74), a sudden freeze frame—pure Brecht—of the British rank and file appears when the schoolboy Stephen’s mother is lecturing him about his anarchistic stirrings, which coalesce with his seeing the ghosts of the composer Edward Elgar and Britain’s eponymous last pagan king. An erotic dream Stephen has merges with his waking reality as a Fuseli-an incubus perches on his bed. The winged angel that materializes beside him on a riverbank is more corporeal than the angels and devils summoned by guilt-ridden or sexually frustrated protagonists in a string of Potter’s non-naturalistic plays. More than mere magical realism, these events and apparitions telegraph Stephen’s political coming of age as a man who realizes he must throw off the chains of gender (he is gay), militarism (he was a school cadet), religion (his vicar father demolishes Christian dogma), and nationalism (he is not of English blood).

Much has been made of Clarke’s Bressonian long takes and his bravura Steadicam shots. Welded to the stripped-down stories of AFN Clarke’s Contact (85), Christine (87, written by the director and Arthur Ellis), Jim Cartwright’s Road (87), and the 39-minute Elephant (89, conceived by Clarke and producer Danny Boyle), these techniques show how far he went toward creating a de-narrativized aesthetic constructed from sound and sustained moving images. The Steadicams came comparatively late in his career, of course, but lengthy shots of characters walking or strolling anxiously—and pregnant with the tensions between them—appear in Clarke’s films of Colin Welland’s The Hallelujah Handshake (70), Roy Minton’s Horace (72, their fourth collaboration), Jonathan Hales’s (pseudonymously credited) Diane (75), and David Leland’s Beloved Enemy (81). If not fully Brechtian, these tuned-up, almost musical sequences draw attention to the conflicts and dangers, originated in personal and political struggles, that Clarke probes relentlessly.

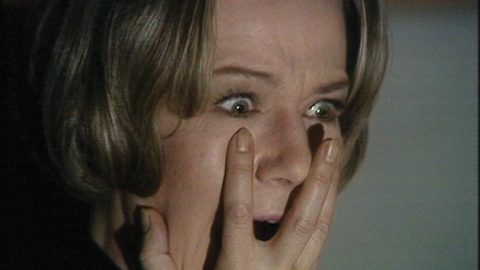

Christine

Before the start of Clarke’s BBC tenure let him loose with a camera in deep, wide cinematic spaces—the Malvern Hills where 7th-century King Penda rescues the burning Stephen from his resurrected foreign birth parents, the projects yard where teenaged Diane dumps her and her father’s stillborn baby in a garbage can—he had quickly developed an impacted style, or camera rhetoric, suited to the charged little studio plays (written by the likes of Minton, Alun Owen, and William Trevor) at Rediffusion. Utilizing shockingly huge close-ups, elliptical body shots (in 1968’s Stella, an angry runaway woman’s thighs, her brutish ex-lover’s nostrils), and the POVs of the emotionally and physically threatened, these dynamic pieces—and the BBC’s 32-minute pub drama Under the Age (72), an indelible early study of Queer anguish—are among the revelations of the Clarke collection. As with the best of the later works, early Clarkean film poetry, agitating and agitative, even in works that communicate the man’s warmth, empathy, and humor, bust the repressive confines of small-screen drama.

Dissent & Disruption: The Complete Alan Clarke at the BBC is available on Blu-ray from the BFI. For more on Alan Clarke, see our May/June 2016 issue.

Graham Fuller is a freelance film critic based in New York.