Adaptation: Patricia Highsmith

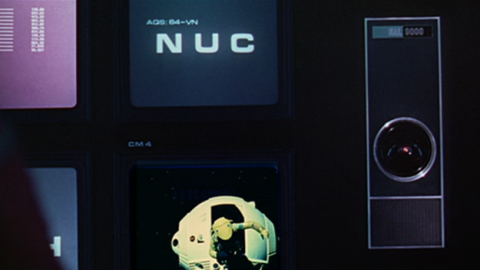

The American Friend

Met a girl, fell in love, glad as I can be

Met a girl, fell in love, glad as I can be

But I think all the time, is she true to me?

’Cause there’s nothing in this world to stop me worryin’ ’bout that girl

These lyrics from The Kinks’s 1965 album Kinda Kinks turn up about 40 minutes into Wim Wenders’s 1977 film The American Friend. Ray Davies, always fond of double meanings, leaves us to decide what he means by “worry”—whether he’s talking about his love for the nameless girl, or the possibility that she’s sleeping with someone else. In practice, of course, it’s difficult to separate these two meanings—maybe being in love involves feeling a little jealous of one’s partner, and maybe there’s an erotic pleasure in jealousy itself: the fantasies of betrayal, the giddy spying, and the smirk of discovery.

The American Friend isn’t a particularly faithful adaptation of its source novel, Ripley’s Game, by Patricia Highsmith, but Wenders’s use of The Kinks almost single-handedly qualifies him as one of Highsmith’s most insightful adapters. For Highsmith, there is no love without disgust or betrayal. Her books are full of seductions—sometimes to sex, sometimes to murder, sometimes to sex and murder—and the seducer’s achievement is always the same: to inspire in his victim a blend of attraction and repulsion that’s far stronger than straight attraction can ever be.

The first thing to say about Patricia Highsmith’s life and work is that there should be nothing left to say about them. Since her death in Locarno, Switzerland in 1995, she’s been the subject of two intelligent biographies—Beautiful Shadow by Andrew Wilson and The Talented Mrs. Highsmith by Joan Schenkar—and not too long ago, W.W. Norton & Co. published a handsome boxed set of the Ripliad, her five novels about the charming sociopath Tom Ripley. And she’s inspired some of the finest works by Alfred Hitchcock, Claude Chabrol, Wenders, Anthony Minghella, and René Clément.

The Talented Mr. Ripley

And yet the well is anything but dry. Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (99), adapted from the first fifth of the Ripliad, launched a tsunami of Highsmith mania in which Hollywood is still swimming. Following the decidedly Highsmithian Gone Girl, Gillian Flynn and David Fincher are reteaming for a remake of Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train, itself based on Highsmith’s 1950 novel. Adrian Lyne is shooting an adaptation of her 1957 book Deep Water; a new Ripley miniseries is in the works; and more.

Highsmith belongs to the small, exclusive group of 20th-century genre novelists—Stephen King, J.G. Ballard, Phillip K. Dick, Elmore Leonard—whose books continue to inspire an endless procession of films, most of which are forgettable but a few of which are masterpieces. In part, these writers are beloved of auteurs for their ability to supply imaginative, evocative premises that cannot be fully realized in any single film and force the auteur to impose his own style upon the material. In this way, an author as original as J.G. Ballard can inspire career-crowning work by two filmmakers of virtually contradictory approaches, Spielberg (Empire of the Sun) and Cronenberg (Crash). Highsmith’s imagination equals and sometimes exceeds those of the other members of the group—the ingenious premise of Strangers on a Train, her freshman effort, launched an entire subgenre of “kill each other’s victims” thrillers, and altogether her novels and short stories have inspired at least 30 films.

Most of the writers I’ve listed make use of stock characters of some kind: detectives, everymen, mad scientists, etc. While Highsmith is no exception—her novels nearly always feature gleeful sadists and remorseless killers—her stock characters don’t make much sense at first glance; in other words, they don’t serve the purpose stock characters are meant to serve. Her most famous psychopath, Tom Ripley, has appeared on screen five times (played by Alain Delon, Dennis Hopper, Matt Damon, John Malkovich, and Barry Pepper), but there has never been a definitive Ripley. This points to a general confusion with the character: is he naïve or calculating? Is he weak or controlling? Is he gay, straight, or sexless? Unusually for the protagonist of a mystery series, he contains multitudes.

Carol

No small part of the uncertainty surrounding Ripley stems from a broader confusion with Highsmith herself, a mystery which Wilson and Schenkar have done remarkably little to solve. Depending on whom you talked to—and she had plenty of friends, including Saul Bellow and Arthur Koestler—she was a misanthrope, a misunderstood social outcast, a loyal friend, or a backstabber. Koestler claimed that she never kept a lover for longer than a few weeks and took keen pleasure in dashing each new partner’s hopes of a happy ending. For years, journalists told the story of how, at the height of her success, she’d invited a young Life reporter to stay at her Italian villa for a week, promising him a long, thoughtful interview. Highsmith welcomed the reporter—then spent the week ignoring him. That she could be charming as well as sadistic is never disputed; the biographer’s challenge is to determine which side was the true one and which was the convenient façade.

Todd Haynes’s Carol, which stars Rooney Mara and Cate Blanchett and opens today, is the first film based on Highsmith’s 1952 novel, The Price of Salt. In her 1992 afterword, Highsmith claims that she based her novel on an encounter she had in her mid-twenties, when she was working at a department store in New York City. An elegant older woman asked the nervous budding author to help her buy a toy for her child. Though Highsmith never saw the woman again, her novel chronicles the love affair between two women— a young department store cashier, Therese Belivet (played by Rooney Mara in Carol), and a middle-aged housewife, Carol Aird (played by Cate Blanchett)—who meet in a store very much like the one where their creator worked.

Because Highsmith, herself a closeted lesbian, returned to write about The Price of Salt so late in her life, there’s been a tendency for critics to treat the text as a skeleton key to her entire oeuvre—there are even those who regard the novel as a failure precisely because Highsmith used it as an opportunity to take off her mask, baring the taboo desires she buried deep in her later work. Reading The Price of Salt 63 years after its release, however, it’s surprising how closely the novel resembles any one of Highsmith’s other books. We’re given barely any information about the nature of Carol and Therese’s desire for one another other than the unambiguous fact of its existence—aside from not being paired with psychosis, there’s little to distinguish Therese’s queerness from that of Tom Ripley or Bruno, the brooding killer in Strangers on a Train.

Strangers on a Train

It’s equal parts impressive and frustrating, then, that Haynes adheres so closely to the tone of Therese and Carol’s romance as it’s depicted in the novel—in other words, that he does so little to explain it. Beginning with the first shot, a nearly Lynchian close-up of a grate, he rubs our faces in physical barriers both permeable (sheets, steamy windows) and impermeable (walls, wooden doors). In a sizeable proportion of Carol’s shots, the secondary characters—including Carol’s husband, Harge, whom she’s divorcing; her daughter, of whom she’s trying to gain custody; Therese’s perpetually ruffled fiancée, Richard; and her artsy friend, Dannie—aren’t doing anything in particular. Instead, they’re literalizing their thematic function: getting in Carol and Therese’s way. Wisely, Haynes recognizes that these people aren’t truly hindering Therese’s love for Carol—in fact, they’re making the object they block more mysterious and enticing. During Therese’s first visit to Carol’s home, she catches her crush arguing with Harge (which leads to the funniest line in the film, “How do you know my wife?”). In the moments before she turns away—and for the virtually first time in the film—her face lights up like a precocious child’s. Here is a woman, Therese realizes, who’s already gone through every milestone Therese has been preparing herself for—courtship, marriage, children—and would give all of them up to be with her.

That Therese is thinking all this about Carol is by no means obvious from a single viewing; it could even be said that the opacity of her attraction is the point. Instead of unlocking Highsmith’s work, Therese and Carol’s romance serves the opposite function: it can only be grasped by studying the rest of Carol, even the rest of Highsmith’s books and films.

In The American Friend, Wim Wenders crafts a subtler homoerotic love triangle than the one in Carol; at the three vertices are Tom Ripley, Jonathan Zimmermann, the innocent picture framer who Ripley tries to seduce into committing murder, and Zimmermann’s saintly wife. The seduction begins, counter intuitively, when Zimmerman refuses to shake Ripley’s hand at an auction, embarrassing the well-mannered psychopath. (One of the strangest aspects of Wenders’s film is Dennis Hopper’s decision to portray Ripley as a cowboy, complete with 10-gallon hat—it seems unlikely that an easy rider could get so miffed.) As punishment, Ripley recommends Zimmermann, who’s dying of leukemia, to his criminal associates. After Zimmermann allows himself to be persuaded to kill, reasoning he’ll make enough money to support his family, Ripley visits him at his frame shop. Knowing full well the agony that Zimmermann’s feeling, he jauntily asks how the day’s going. Wenders’s pairing of revenge and green light recalls Othello, a play that also shows up in The Talented Mr. Ripley 22 years later. As it’s been suggested of Iago, furthermore, Ripley seems motivated by homoerotic attraction as well as revenge, his desire to hurt and humiliate Zimmermann being only one stage in his plan to win the man’s affections and overturn the events at the auction.

The Cry of the Owl

The most sadistic acts in Highsmith’s books are never physical; they’re rooted in precise, often economic, exchanges of power, information, or money. In The Talented Mr. Ripley, both the book and the two films based on it—Purple Noon and The Talented Mr. Ripley—Ripley travels to Italy on the dollar of Herbert Greenleaf, the wealthy father of the young playboy Dickie Greenleaf. Ripley has pretended to be an old friend of Dickie’s from Princeton, and Greenleaf has offered him a handsome reward if he can persuade Dickie to return from Italy to America. When Ripley ingratiates himself with Dickie and Dickie’s fiancée, Marge, he switches benefactors; then, when Dickie threatens to cut off his allowance, he decides to murder Dickie and steal his identity. Power and control take on still more complex forms in Highsmith’s novel The Cry of the Owl, as well as Claude Chabrol’s agonizingly taut film of the same name. The protagonist, Robert, has just divorced his bitter wife, Nickie, and moved to the suburbs. Gradually, he realizes that Nickie has bribed Greg, Robert’s hotheaded neighbor, to fake his own death, knowing that Robert will be blamed. There’s something both awesome and pathetic about so much ingenuity directed at someone so ordinary—one wonders why Nickie couldn’t apply her mind to curing cancer or solving the energy crisis. (The same could be asked of Amy Dunne, the villainess of Gone Girl.)

In The Price of Salt, the two main characters battle for money and information—the only difference between their relationship and that of the characters in The Cry of the Owl or The Talented Mr. Ripley is that they’re trying to love, not kill, one another. Carol lavishes gifts on her young, naïve lover (just as, years later, Highsmith was said to lavish these things on her own conquests), and in general money plays a critical role in their relationship. When Carol first meets Therese at the department store, she’s completing a transaction (buying a doll for her daughter), just as she makes it clear she’s doing when she later takes Therese out to lunch. As the relationship blossoms, she writes Therese checks, always saying that it “gives her pleasure” to do so; eventually, the checks becomes so routine that Therese can only bear to pay for things when Carol isn’t watching. Carol’s cool command of money, and Therese’s willingness to accept it from her, suggest something about the imbalance of power that isn’t immediately obvious from reading The Cry of the Owl; namely, that there’s pleasure to be had in submitting to another human being’s authority—doing so can be kinky, BSDM-y fun.

There’s no rule that a good adaptation is a faithful adaptation, and often, the finest Highsmith films (Purple Noon, The American Friend, Strangers on a Train, The Cry of the Owl) take the greatest liberties with their source texts. While Haynes preserves The Price of Salt’s most obvious trappings of lesbian kink—red nail polish, a big gothic house, an older, more confident woman and her young, naïve apprentice—he simplifies its fascinating muddle of love, power, and sadism. Noticeably absent from Carol is any hint of the domestic abuse found in other recent depictions of 1950s suburbia, including (very briefly) Haynes’s own Far From Heaven. Yet there’s no corresponding focus on more abstract—and ubiquitous—forms of coercion. The only characters who regularly use money and information for control are Harge, the smarmy private investigator he hires, and Dannie, who tries and fails to parlay his photography connections into a date with Therese. In her own work, Highsmith doesn’t permit such easy equations between villainy and power—the main character is the manipulator as well as the manipulated.

Carol

Nor could Haynes’s New York be mistaken for Highsmith’s. Highsmith, no less than her contemporaries Ginsberg and Kerouac, despised billboards, holiday sales, “everything must go” signs, and the like. (After 1963, she left the U.S. and never came back.) Many of the recent adaptations of her novels, such as The Two Faces of January, highlight their exotic continental settings, losing sight of the consumerist nausea that prompts the characters to thirst for escape in the first place—one can’t grasp Ripley’s attraction to Dickie, with his boats and Italian beaches, without also grasping his disgust with Coca Cola and McDonald’s. Haynes doesn’t make the mistake of fetishizing the not-too-distant past, Mad Men-style, but he stops short of conveying the tawdriness of the era in which his film plays out. The same misty glow presides over every scene, whether it takes place in a department store, a house, or a bar, and many of his evocations of the past aren’t tied to historical events at all; as in Far From Heaven, they’re homages to filmmakers of the era. (When Therese first sees Carol on the other side of the store, for instance, she breaks eye contact for a few seconds, only to find Carol teleported, Hitchcock-style, right in front of her.) Even if Haynes doesn’t invest in homage as heavily as he’s done previously, it’s telling that his reconstructions of New York take inspiration from the street photography of Vivian Maier, praised by the equally influential photographer Joel Meyerowitz for her “human understanding, warmth, and playfulness.” Few jabs at the culture that keeps Carol, Therese, and Highsmith in the closet are attempted—certainly nothing on par with an acidic Highsmith line like “Santa Claus was supposed to bring the dolls, Santa Claus represented by the frantic faces and clawing hands.”

And yet Carol, in addition to its own aesthetic merits, is a major contribution to the art of Highsmith adaptation. Post-Production Code Highsmith films face a dilemma: depicting their characters’ sexuality and psychosis with a degree of explicitness that Highsmith herself, confronted with censorship and publishing norms, never had to deal with. By preserving an aura of ambiguity, contemporary films run the risk of appearing deliberately old-fashioned (Richard Brody, writing in The New Yorker, recently criticized The American Friend on these grounds), but by exposing their protagonists’ innermost secrets, they have a habit of humanizing Highsmith’s characters and depriving her books of their bitter, satirical edge—the very quality that endeared them to readers in the first place. The Talented Mr. Ripley commits the second error by portraying Ripley as a shy, homosexual nerd whose murders are practically accidents. (In the film, it’s Dickie who lashes out first, and a hotel clerk who gives Ripley the idea to impersonate his victim.) Late in the film, Matt Damon, his voice lapsing into Good Will Hunting vowels, expresses his desire to “take a giant eraser and rub everything out, starting with myself.” That he’s speaking to his lover, Peter Smith-Kingsley, shortly before murdering him in a final bid for freedom, hammers home the point that Ripley is a victim of homophobia, bullied into a life of crime. Sexuality is, in short, the “key” (a conspicuous symbol in the latter half of Minghella’s film) to understanding this character.

The sexual encounter that occurs between Therese and Carol might have been the dramatic highpoint of a weaker film. For Haynes, it solves and reveals nothing; indeed, much of the time it’s impossible to tell exactly what we’re looking at. The tangled close-ups of Mara and Blanchett’s bodies have the uncanniness of Man Ray’s Surrealist photography, so that unlike the long sex scene in Blue Is The Warmest Color (another recent Cannes success about lesbian lovers), their lovemaking isn’t purely a moment of gratification, either for them or for us. Therese and Carol continue to look past one another, blindly savoring their moment together but also aware that their affair will change, and quite possibly destroy, the lives they’ve made for themselves. Their sex is, one might say, another version of the cross-country road trip they’re taking: an attempt to escape societal expectations that ends up reinforcing the impossibility of any kind of escape. Haynes, steering elegantly between the prim and the graphic, avoids his predecessors’ mistakes; while it’s impossible to say what kind of love scenes Highsmith would have authored had she lived half a century later, he captures the sense of eerie kinkiness that, in retrospect, has been missing from Highsmith films for some time.

Purple Noon

At times, directors have found it necessary to dress up Highsmith in sentimentalism and moralism—never more outrageously than in the last minute of Purple Noon, during which Tom Ripley is suddenly and implausibly brought to justice for his crimes. Clément ruins the tone of Highsmith’s novel so completely that it’s easy to forget Highsmith herself wrote a fair number of convenient, dramatically unsatisfying, and deeply moral endings. There’s no particular reason why Chester, the callous antihero of The Two Faces of January, would confess to his crimes on his deathbed, clearing his equally wicked enemy, Rydal, of all suspicion. In the similarly epiphanic final moments of Ripley’s Game, the coldest of Highsmith’s villains shows a sensitive side as he tries to honor the memory of his dead accomplice. That the three films based on these two books go off the rails in their final minutes (literally so in The American Friend) isn’t only a result of the usual limits of cinematic adaptation. Rather, it suggests that Highsmith couldn’t make up her own mind about her own characters—whether they were purely cold and acquisitive, or if there was at least a little warmth in their eyes.

The ending of Carol—at once an elaborate homage to and a 180-degree reversal of Brief Encounter—falls into the same category as those of Ripley’s Game and The Two Faces of January. No “structural” explanation exists for Therese and Carol’s reconciliation (actually, a cameo by Portlandia’s Carrie Brownstein suggested that Therese would take a new lover); this is, as Terry Castle noted in her essay on the novel, a happy ending that exists purely for the sake of happiness. Highsmith writes, “Carol saw her, seemed to stare at her incredulously a moment while Therese watched the slow smile growing.” In his film’s final seconds, Haynes plays virtuosic riffs and variations on this sentence, finally allowing Therese and Carol the thing he’s denied them: a prolonged stare. As the stare stretches on and on, we’re reminded of how little we know about Carol and Therese, even after two hours, and how little they know about each other. There are plenty of questions we might ask—Will their love be any different?; What will they tell people?; Where will they live?; Where could they live? But it’s refreshing, given how many films have tried to update Highsmith’s novels by cramming more information into the story, that Haynes doesn’t answer these questions—and tacitly acknowledges that he’s no more capable of doing so than was Highsmith in 1952.