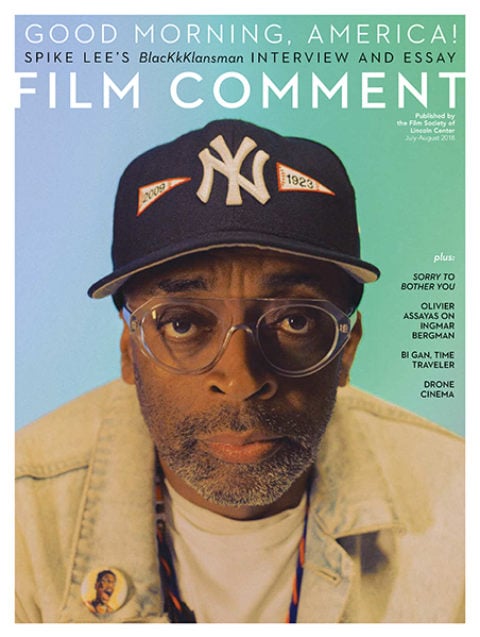

Worldly Wise

On April 5, Isao Takahata, co-founder of Studio Ghibli, passed away at the age of 82. For most Westerners, especially for those who became fans post–Princess Mononoke, Studio Ghibli is simply a synonym for Hayao Miyazaki’s films and imitators. Yet the studio and Miyazaki’s legacy would not exist without Takahata, an animation director who was an instrumental force in advancing Japanese animation in terms of technical skill and narrative refinement. Prior to Takahata’s pioneering work in the late 1960s and ’70s, anime was strictly kiddie stuff, intent on imitating the form and success outlined by Disney. Rather than simply reacting against or satirizing this variety of hand-drawn animated film (as has been the case in America for the past several decades, even though that type of Disney kiddie flick doesn’t exist anymore), Takahata continuously pushed the medium in bold new directions, usually taking the form of work that was more mature and less commercially viable. His best-known title outside of Japan—the devastating Grave of the Fireflies (1988)—is a testament to the power of animation to create worlds and feelings that live-action films rarely even aspire to. In a medium that necessarily recycles images to create the illusion of movement, Takahata stands out as an artist who never repeated himself.

A notorious perfectionist—so much so that he frequently missed deadlines, sometimes by years—Takahata has been credited by collaborators as “the serious one” who pushed Miyazaki toward more complex themes in seminal works like Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and Castle in the Sky (1986). Nevertheless, there’s no need to make the argument that one Ghibli co-founder was secretly superior to the other, or that there was anything uneasy about their partnership. The work of Miyazaki and Takahata was always collaborative, taking the form of a friendly competition in the latter part of their careers when they directed and wrote films separately. (Studio Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki gave Takahata’s The Tale of The Princess Kaguya and Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises the same release date as a means of motivation; despite beginning production years earlier, Takahata’s film went to Japanese theaters four months after Miyazaki’s.) The two men met while working at Toei Doga, the country’s major animation studio, which sought to be the Disney of Asia, and bonded over their shared passion for literature and desire to push their work and the animation medium forward. Miyazaki (who at the time was a union rep) broke union rules to work over the weekends, sans AC, as scene designer on Takahata’s first directorial feature, The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun (1968). It was an adaptation of an Ainu tale that was transposed to a Scandinavian kingdom at the behest of the studio (the Ainu are indigenous peoples that have been discriminated against by ethnic Japanese). The story broke with previous cartoon folklore adaptations by emphasizing psychological realism, while the animation featured ambitious designs, smoother cuts and movements, and more realistic fights—no “Mickey Mousing” to be seen.

Like Paul Grimault’s The King and the Mockingbird (first released in 1952)—the film that inspired Takahata, who had a degree in French literature, to go into animation—The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun went over budget and was released with unfinished scenes. After its limited run and poor performance at the box office, Takahata was permanently demoted to assistant director at Toei. Miyazaki and Takahata left the company in 1971, but continued to work together at various independent studios for the rest of the decade. Some of these early collaborations were overtly mercenary, such as the TV series Lupin the Third (1971-72), whose original director, Masaaki Osumi, quit in protest of making it more kid-friendly, allowing Takahata and Miyazaki to step in and co-direct many episodes; and Panda! Go Panda! (1972), a cash-in on the era’s panda fad that was made after the pair were denied the rights to adapt Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking (and therefore featured a little redheaded girl with pigtails, Marimekko-style prints, and lots of tulips). Nevertheless, these TV episodes and theatrical films showed the duo’s visual and narrative inventiveness with small budgets, and still offered sui generis pleasures for casual and die-hard fans alike. Directly and indirectly, these projects also influenced some of Studio Ghibli’s most iconic films: Miyazaki reused some of his designs for po-faced, oversized father character PapaPanda for My Neighbor Totoro (1988), and the success of the Miyazaki-directed Lupin the Third feature The Castle of Cagliostro (1979) would allow them to create their own company

The Tale of The Princess Kaguya. Photo: © 1994 Hatake Jimusho - Studio Ghibli - NH

Takahata’s interest in adapting Western literature into anime soon found a home in Calpis Comic Theater (which eventually came to be known as World Masterpiece Theater), a long-running television show. Miyazaki designed characters and layouts for animated versions of Johanna Spyri’s Heidi: Girl of the Alps (1974); Marco, 3000 Leagues in Search for Mother (1976, from a short story by Edmondo De Amicis); and Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables (1979)—all of which Takahata directed. Like their sources, these series strove to emphasize quotidian actions and emotion rather than fantasy or adventure; Takahata later attributed this to his interest in Italian neorealism. While a cute little cartoon girl running through the Alps is far removed from Anna Magnani running through broken streets in Rome: Open City, these quiet, slower-paced episodes do pursue something meditative. Takahata’s own childhood during the firebombing in World War II was closer to Rossellini’s film; in an interview in 2015, he stated, “Heidi’s carefree nature stems from my ideal image of what a child should be like—something I couldn’t be.” Unlike their live-action inspirations, these are not semi-documentary shots that happen to capture life unaware, but rather a very precise approximation of that type of filmmaking rendered through drawings.

The question of what and what not to include is crucial in drawing, be it moving or still. As Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko has argued, rendering a character’s face anonymous through a mask makes it easier for the reader/viewer to identify with and project their urges onto them; fewer details open up more possibilities for the mind. Most of the first episode of Anne of Green Gables is spent building up the Cuthberts’ meeting with Anne: Marilla (Fumie Kitahara) speaks at length with her neighbor about their decision to adopt a young boy, while Anne (Eiko Yamada) quietly entertains herself alone at the train station, using the tracks like a tightrope while waiting for Matthew (Ryuji Saikachi). On her long ride back to the farm with Matthew, Anne yammers nonstop, marveling at the green fields and trees around her, which are rendered with simplicity but attention to detail. The grasses are not animated, yet they have a tactility about them; it is an invitation to remember the summers we too have experienced. However, as they approach “the Avenue,” a group of trees with pinkish white flowers, her imagination runs away with her. The flowers begin swirling around in a cloud, lifting her up to the heavens while orchestral music swells. As their carriage draws away from the trees, the daydream fades, and Anne sadly looks back as the blossoms slowly disappear under the horizon. The moment of abstraction expresses the private, swoony reveries of childhood, a stark contrast to the realism and dialogue that preceded it.

The hypnotic and healing power of nature that Anne feels ran throughout Takahata’s work, and sometimes became the defining premise. Gauche the Cellist (1982), his last feature film before co-founding Studio Ghibli, is an adaptation of a short story by Kenji Miyazawa about a small-town musician whose playing improves before a big concert after nightly visits from talking animals. This simple scenario is enhanced through the animation, which offers languorous pans across the hills and valleys near Gauche’s house, as well as flights of fancy during musical sequences where the drawings take on a more expressionist tone. These are used to illustrate moments when the man-made transcendence of the orchestra’s music becomes one with the transcendence of nature: the room in which they’re playing fades away and is replaced by the majesty of the environment. (There’s also comedy: as Gauche drives away a begging cat by playing a modernist piece titled “Tiger Hunt in India,” there’s a playfully distorted POV shot from the cat’s point of view in which Gauche and his cello are distorted, appearing to bubble like a lava lamp, and drawn with finer lines that threaten to pop open.) These flourishes don’t feel like eye candy thrown in to awe little ones who might be getting bored. Rather, they are seamlessly integrated into the story to stress the importance of hard work and listening.

Pom Poko. Credit: © 1994 Hatake Jimusho - Studio Ghibli - NH

Due to such painstaking attention to detail—Shunji Saida, the key animator who drew Gauche, learned how to play cello in order to get the fingering right—the movie took six years to complete. After failing to adapt Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo (which Miyazaki described as his worst work experience) and producing the environmental epic Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which cemented Miyazaki’s reputation, Takahata went to Yanagawa, a 30-square-mile city with 290 miles of canals, in search of inspiration for a follow-up animated feature. Enchanted by the rich culture that had arisen from these canals, Takahata wrote, co-produced, and directed his only live-action film, a three-hour documentary about the city. Funded by the profits of Nausicaä, The Story of Yanagawa’s Canals (1987) was never going to be a commercially viable proposition (to cover the costs, Miyazaki and other producers began work on Laputa)—it’s a dense but accessible work. Whether floating down the canals inside of a donkobune (river boat), glimpsing the all-night party that happens when the canals are dredged, or observing the various festivals that take place in and around the water, there’s an incredible level of precision about showing how things work together. Many of the camera movements and editing rhythms found in Heidi, Gauche, and later works abound here: slow pans across a landscape, a medium shot of an action inside that landscape that doesn’t necessarily add to the story but adds emotion. Such methodical pacing and interest in small gestures became more common in animation after Takahata made it an integral part of his style.

Yanagawa’s canals were grossly polluted during the 1960s economic boom, and were nearly converted into sewers. Shocking “before and after” photographs of the canals, the elaborate maintenance process of townsfolk and leaders, and the return of festivals centered around (or taking place on) the water, all stress the importance of things that were lost by Japan’s postwar wealth.

The negative aspects of this era would figure prominently into Takahata’s fourth feature (and only original screenplay) for Ghibli, Pom Poko (1994), a funny and sad tale of tanuki (raccoon-dogs) in what would become Tokyo’s New Town suburb. Known as fertile tricksters in Japanese folklore (signified by their gigantic testicles, bowdlerized as “racoon pouches” in the dubbed English version), the tanuki cease warring with each other in the hopes of stopping the construction that’s destroying their forests. They learn how to transform into other objects, animals, people, and demons, and put on several incredible shows for the humans that are full of references to Japanese history and mythology. Just as in real life, the humans either ignore or misinterpret these urgent signs from nature; in a hilarious subplot, a theme park owner takes credit for one of the shows and is summarily punished by the tanuki.

In their final attempt to deter the encroachment on their habitat, the tanuki transform the suburb into the undeveloped landscape it was before the boom, turning back the clock the same way the people of Yanagawa did. But unlike Yanagawa, this is just a fantasy, something that Pom Poko repeatedly acknowledges by representing the tanuki in three different styles of drawing: semi-realistically, like something you’d see in a science textbook; cutely standing on hind legs and wearing clothing; and as super-simplified, gag-like cartoons. When a tanuki dies by being hit by a car, it is drawn in the realistic style; when they party or go to fight against the humans, using their shape-shifting abilities, they’re drawn in the second, anthropomorphized style, which, because of the futility of their efforts, often feels just as sad.

Grave of the Fireflies

The complicated emotional registers of Pom Poko are also found in the two animated films that preceded it: Grave of the Fireflies and Only Yesterday (1991). Based on a story by Akiyuki Nosaka, Grave of the Fireflies was released the same day as My Neighbor Totoro (sometimes on a double bill). As in Pom Poko, Takahata harnesses the power of animation to create a world that no longer exists with a level of detail that would have been incredibly expensive to create in live-action. The film follows two war orphans, 13-year-old Seita (Tsutomu Tatsumi) and 4-year-old Setsuko (Ayano Shiraishi, an actual 4-year-old), during the American firebombing campaign in Kobe. The pain and devastation caused becomes palpable immediately. But rather than being an anti-war film or apologia for Japan’s role in WWII, Grave of the Fireflies explores the cruelty of human behavior at macro and micro levels: both sides of the war evince man’s inhumanity to man, but Seita’s arrogance condemns his sister to a painful, preventable death of starvation.

As Takahata has noted in interviews, Seita acts more like a child of the postwar era—headstrong, independent, unwilling to make nice with his traditional (and seemingly unreasonable) aunt—and not the noble ideal of the time. It’s a decision that encourages children to look at their own behavior and make choices that are for the greater good rather than themselves, and to connect and identify with the story in a deeper way. Undoubtedly one of the saddest films ever made, Grave of the Fireflies never feels cloying, manipulative, or beyond the realm of possibility.

Childhood clashes with a different era in Only Yesterday. Taeko, an independent but aimless office worker living in Tokyo, where she was born and raised, takes her vacations in rural parts of Japan; this summer, she chooses the Yamagata countryside. Through her encounters with Toshio, a young farmer, she recounts and relives various memories of her 10-year-old self. Her youth was far from carefree—much of what she remembers are arguments with her older sisters, educational and social failings at school, and her father squashing her dreams of becoming an actress. In these flashbacks, parts of the world are left as undrawn white spaces, literal holes in a fading memory. (The inside of her house, the place that she remembers best, is the most detailed.) At the end, she decides to stay in the country and begin a relationship with Toshio. The ending is cute overload, with children from her memories helping her out of the Tokyo-bound train, leading her to her newfound love, and joyously marching through the streets. All of this feels like a tease, yet Taeko finally seems happy to be moving toward something more satisfying than being stuck in the same dysfunctional place.

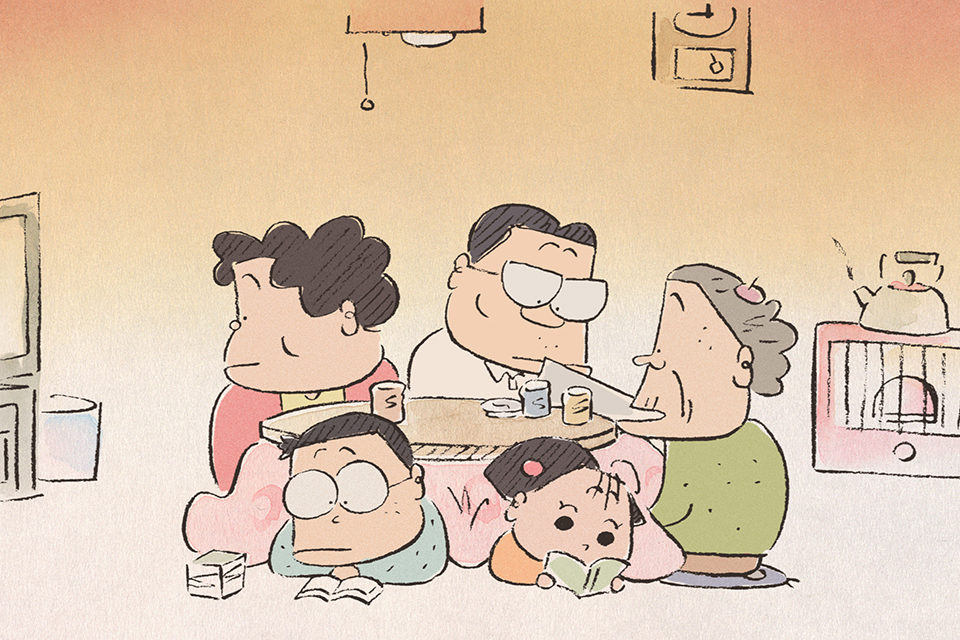

Takahata’s My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999) and The Tale of The Princess Kaguya (2013) also make significant use of negative space (or mu) in the frame, inspired by older traditions in Japanese art, such as scrollmaking. This fascination with appearing “unfinished” and seeing how emotive a simplistic drawing could be came to define the final part of Takahata’s career. My Neighbors the Yamadas is a series of vignettes about a less-than-perfect family, bookended by haiku by Basho and other great Japanese poets. The complexity of drawing varies when things get “realer”—such as during an encounter with a motorcycle gang hanging out on their block. With trembling outlines, Mr. Yamada is more photo-realistic as he approaches them and tells them to leave; when they refuse, his wife and mother appear in their characteristic, caricatured style to diffuse the situation with drums and singing. This is followed by a fantasy in which Mr. Yamada turns into the Masked Rider, easily disposing of the bandits with super-strength and acrobatics. My Neighbors the Yamadas feels more like a collection of Buddhist parables than a three-act-structured film—an approach that often helps you think toward a lesson rather than simply stating the moral. The Tale of The Princess Kaguya, a retelling of the classic Japanese myth about a princess sent to earth from the moon, is animated in a style that mimics the brushwork of ancient scrolls. Although the narrative would likely hold no surprises for a Japanese viewer, it’s nevertheless a powerful and thoughtful meditation on humanity’s interactions with the natural and supernatural, and features an ending that is ambiguously hopeful.

My Neighbors the Yamadas. Photo: © 1999 Hisaichi Ishii - Hatake Jimusho - Studio Ghibli - NHD

As our media culture continues to fracture, expectations about age have fallen away, and cartoons are no longer limited to Saturday mornings—the unspoken bias that animated movies are “for kids” continues in the United States. Even animation that is “adult-oriented” works primarily in a comedic register rather than as something more emotionally complex. On April 4—ironically, the day before Takahata passed away—Netflix announced that they were commissioning a new animated series “for adults,” from the creators of Brickleberry, a Comedy Central animated series about the filthy, madcap goings-on in a national park. This was a racy riff on Yogi Bear and Camp Jellystone, a character and conceit that last had an “original” series in 1991. Though American independent print and web comics offer truly thoughtful and artful introspection, as well as new comedic directions, American animation for adults remains not that adult-oriented or engaged with the contemporary moment. Pixar, the dominant brand in family-friendly animation, offers many nods to adult viewers but the studio appears uninterested in making a feature specifically for them.

Throughout Takahata’s career, he sought to make difficult, sorrowful, humorous, and thoughtful animated films that defied simple categorization and did more than just teach a lesson. John Lasseter was a big fan of Castle of Cagliostro, but in any case, Pixar seems content to follow its own formula for critical success, doling out unobjectionable social commentary through colorful creations. While more creative and ambitious animation thrives in miniature (such as the shorts of Don Hertzfeldt, a master of form and existential dread), in overseas projects (like Makoto Shinkai’s clever and poignant Your Name), or as part of installations, it remains for a successor to Takahata to push a popular version of the form forward.

Violet Lucca is the web editor and digital director at Harper’s magazine and a member of the New York Film Critics’ Circle. She was formerly the digital producer at Film Comment.