Willing Sinner: Pedro Almodóvar

My first glimpse of Pedro Almodóvar’s troupe from Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown was the black, quilted, free-form sculpture actress Rossy de Palma had taken as a hat at the Venice Film Festival. An expressionist answer to the mantilla, it floated above the crush like a levitating bonsai tree and let you know where the girl-gang that comprised the cast was hanging out. Women on the Verge is to formula filmmaking and canned emotion what Andy Warhol’s soup can was to processed food—a camp satire of every breakup that ever left a woman sobbing in a melodrama and a send-up of every kind of TV soap, including laundry detergent commercials. The plot is a perfect web of cliches, the sets a parade of posters of great film oldies, and it easily stole the show from Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ-which was supposed to be the Big Deal at Venice but which the ministers of culture let through without a fuss and which failed to inspire the riot that Catholics had been promising us for weeks. Pedro’s women were the rage, and they seemed on the verge of nervous breakdowns of their own, squealing and squeezing one another’s hands in giggly excitement. It was, as Noel Coward purred, refreshing.

Almodóvar’s humor was sardonic. He talked about The Last Ostentation of…, and asked what prize he would like he replied, “First prize for me [Women on the Verge] would be having the culture ministers ban it.” It won the award for best screenplay. Free from world opinion, the bureaucrats might’ve nixed it since Almodóvar’s seven feature-length films are anti-clerical to a frame and dismiss dogma of every sort-priestly, feminist, fascist, gay lib-like a queen in Bette Davis drag banishing dullards from the bar. Political thinking is too crude, literal , and neat to explain our passions. Almodóvar fears government and church repression, Franco and the Ophus Dei (a right-wing Catholic cult popular in Spain and Italy), but also any group-think from sex roles to manners to well-meaning radicals who would overthrow both. As he told the crowd in Venice, ”It’s important to know who your enemies are.”

He put it with more characteristic tone to a woman at the New York Film Festival who complained about his political inconsistencies. “I don’t like any kind of militancy, and I don’t like telephones. Passion has its own irrational rules, and like indifference, it can drive people to sublime or dangerous extremes. Society is preoccupied with controlling passion because it’s a disequilibrium, but for the individual it is undeniably the only motor that gives sense to life.”

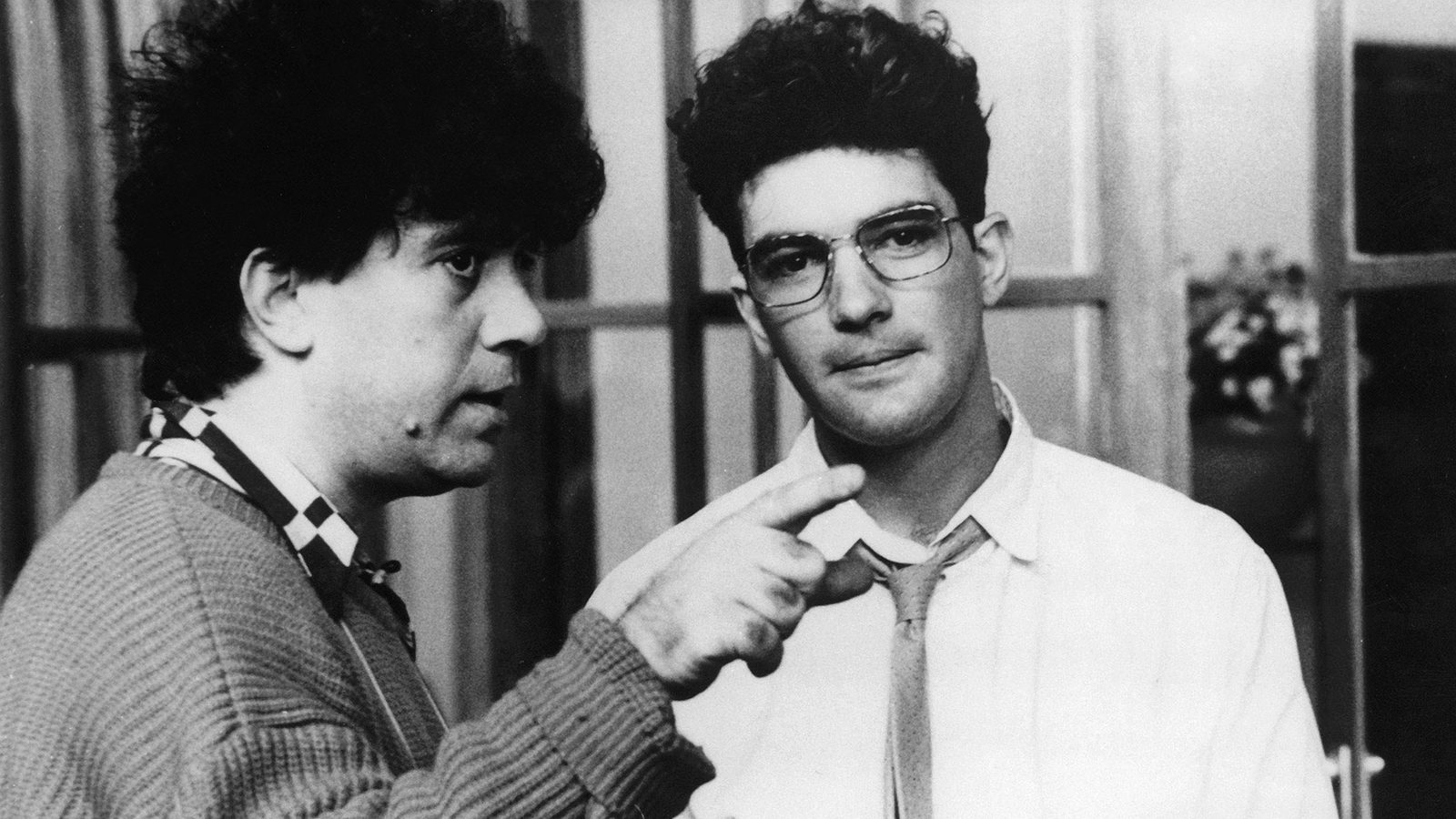

Antonio Banderas and Maria Barranco in Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown (Pedro Almodóvar, 1988)

Almodóvar feels the confusion between desire and public or political policy is greater here in the U.S. than at home. “Not that Spain is so wonderful, but even the people on the right are closer to human weakness, temptation, error. They understand it’s part of life, it’s all mixed up together, and that’s the way people really are. Here you pretend people don’t have desires or you talk about it with such violent curiosity, like you’ve never seen it before, like you have no experience with yourselves. Passion is what moves you, you can’t avoid it.”

Almodóvar looks to the overblown theatrics of studio-era films and TV melodramas where desire, betrayal, and forgiveness expose themselves with leisure. Re-worked through his sense of camp, they become a comingout party for obsession set on the stage of grand illusion, and everyone comes dressed to kill. His characters—nuns, cads, battle-axes, jilted women and innocent youths—are costumed in irony. Their emotions are archetypical and played with effortless sarcasm. Almodóvar has done for film what choreographer Mark Morris did for dance.He took the sardonic attitude born in the gay ghetto—like Jewish humor, as a smart-ass way to survive society’s hate—and made it into a sensibility to look at the world.

In Verge women are dumped and left to cope. In the 1986 Law of Desire a gay man forgives the boy he loves, even for his murderous homophobic rampages, and the sanest character is a post-op transsexual who, Freudianly enough, had an affair with her father when she was a boy. Her “confession” of her past reads as the encyclopedia of the crises of daytime TV.

In Matador (also 1986), Almodóvar castrates machismo and its union of sex and power, while insisting that the triggers to arousal—boots, stilettos, a matador’s cape—are misunderstood by religious fury and liberal concern. Calling it his most difficult work, Almodóvar made the film unavoidably erotic-in one scene holding the camera close to a kiss while, off-camera, stripping the actors below the waist. In the 1983 Dark Habits, a convent rigs up phony miracles to milk money out of believers and support the sisters’ religious experience with cocaine.

“Camp makes you look at our human situation with irony,” Almodóvar says. “It’s much more interesting to take camp out of a gay context and use it to talk about anything, everything, but to do that you must show how much you love it, how much you enjoy camp. Otherwise you look like you’re just making fun. In camp you sympathize with lack of power, like the pathos of sentimental songs. This is kitsch, and you are conscious that it is, but that consciousness is full of irony, never criticism. You cannot take camp out of its original context if you feel like an intellectual using this…this…element of theirs. To use it outside, you have to celebrate it, to make an orgy of camp. Anyway, it’s a sensibility. Either you have it or you don’t.”

Pedro Almodóvar, Eva Cobo, and Chus Lampreave on the set of Matador (Pedro Almodóvar, 1986)

Almodóvar’s mentors, Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, and Luis Buñuel-his Trinity, as he calls them-are not known for their camp, but they taught him how to overlay opposites, to make absurd juxtapositions work, which always serves an ironic stance. Hitchcock made “high art” images understandable to a popular audience and “made the unbelievable believable.” Wilder told painful, realistic stories as comedies. Buñuel came closest to camp, especially his Mexican period, when he transformed outrageously bad plays and actors with the subtlety of tarts into biting cinema. He also dropped dreams and surrealist fantasies into workaday scenes “without,” Almodóvar noted,“even changing the lighting.” Almodóvar was also influenced by Tennessee Williams’ melodramas with Elizabeth Taylor and Natalie Wood, Peyton Place, Jean Renoir, and Roberto Rossellini. Asked at Verge’s first New York screening if he felt any kinship with Rainer Werner Fassbinder, he replied, “Oh, yes, we like the same kinds of bodies, cocaine, and we’re both fat.”

Privately he said, “When you begin to dream about being a director you dream about actors, not directqrs. Awareness of directors comes later. My dream was Bette Davis—I adore the violence in her character, her autonomy—or Kate Hepburn and Marilyn Monroe. Contemporary actors don’t give this kind of impression. It was a part of the studio system, which was awful for the people who worked in it but created actors with an extraordinary capacity to be larger than life.“ The race of actors has changed now, even physically. Actors are like normal people, but a normal person wasn’t a Rita Hayworth. In a film like Matador, which is a fable, fantastic, I want grand actors from the pedestal. For leading lady I would’ve cast the young Ava Gardner.”

“I wanted to do a woman in an emotionally extreme situation,” Almodóvar said, explaining how Verge got started. (What else is new?) “So I thought of the short Cocteau piece The Human Voice, just a woman by a phone, waiting. Then I start to write, and my own life gets mixed in. I remember sitting by the phone one day, waiting for a certain person to call, ready to throw myself out the window….”

Antonio Banderas, Maria Barranco, Rossy De Palma, Carmen Maura, Julieta Serrano, and Pedro Almodóvar on the set of Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown (Pedro Almodóvar, 1988)

Why make the hero a woman, then? Is this part of a gay sensibility, of camp?

“Not because I’m gay. I am much more curious about women. I always listen to their conversations in buses and subways. I’m becoming a specialist. Bergman [the inveterate heterosexual] also knows how to talk to women, to show them. Women are more spontaneous and more surprising as dramatic subjects, and my spontaneity is easier to conduct through them.” No other male Spanish directors talk about the“female universe,” said Almodóvar,“and there are really only two women directors in Spain. It’s also a country of great actresses not actors. Men are too inflexible; they are condemned to play their Spanish macho role.“ So your interest in women is not because you’re gay but because you’re “spontaneous?”

“Yes…well.” Almodóvar is often impulsive and childishly excitable, but this was the first time I saw him blush.

“We can find a lot of bitchy women in movies who have the masculine impulse behind them, but my women are not men disguised as women. I only did something like that once, in Matador. The relationship between the lovers is a bullfight, and she is the bullfighter. A woman needs a huge will and autonomy to do that, to become male simply because she wants it.”

But Matador is so thoroughly critical of masculinity.

“I hope so. There’s something desperate in her imitation of men, a desperation to be male that comes from the society, the machismo she lives in.“ The desperation the heroine feels in Verge is much more commonly female.“Men don’t know how to leave women, so they say they love them while they’re really running away. This hypocrisy leaves women with so much frustrated confusion. During a relationship, women have more resilience and will endure much more pain than men. But when it’s time to break up, women will face it. They have more common sense, men are lazier; 80 percent of the petitions for divorce in Spain are filed by women.”

Why?

“You tell me. I think it’s because women are practical. This is universal, but it’s particularly Spanish for men not to be honest with women. It’s the heredity of the Latin lover. A man can never say anything disagreeable to a woman, so they lie.”

Is it different for gay couples?

“In the gay relationships I know they don’t play male and female roles. Sometimes gay couples can be more sincere because there’s nothing holding them together but their feelings-no contract, no family, usually less economic dependence. But you know you can’t generalize.

“Breaking up is pathetic no matter what or who, because it obliges you to begin a new life, and we’re all fragile and weak. There’s no point in the middle when you think you’ll drive yourself crazy, but…wait awhile.”