Wild Bill Richert

Bill Richert and Tony Perkins were standing on top of the world when somebody cut the power. From this eyrie, banked by vast, blinking computers and backed by a satellite picture of Earth, John Cerutti (Perkins) could monitor every salient face of the globe, catalogue it, and consider its implications for the financial and political future of the Kegan dynasty—the Kennedyesque family and megaconglomerate whose ins and outs define the texture of modem reality in Richard Condon’s novel Winter Kills. Richert had whipped this kaleidoscopic narrative into a fluid screenplay and was within a week of completing shooting. But in the giddy orbits of other, less reliably monitored galaxies, the production money had twinkled away. Now, on the MGM soundstage floor far below, union representatives with no sense of irony were killing the lights, shutting the picture down.

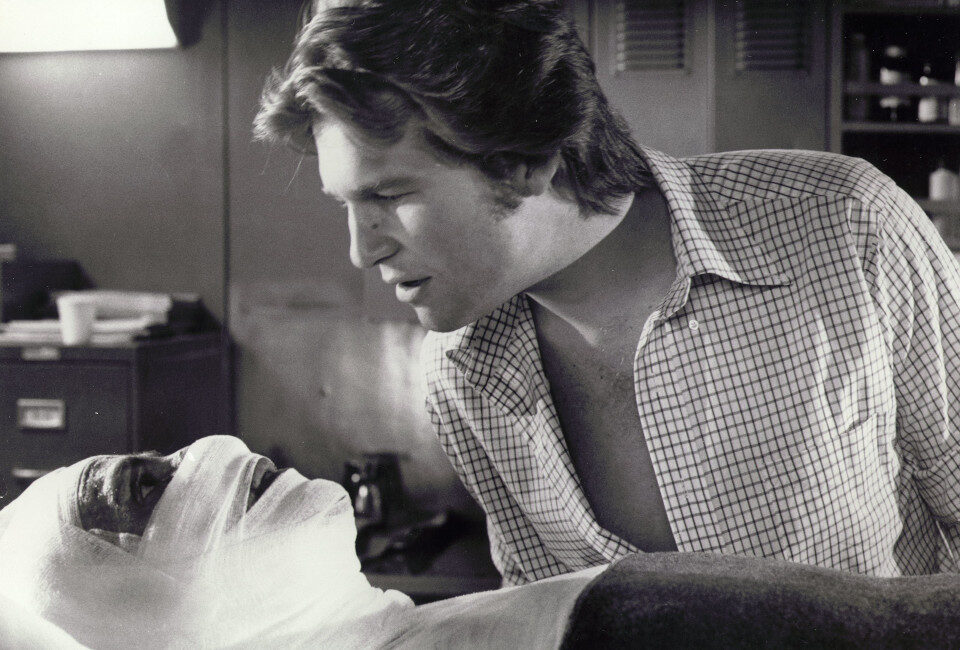

“Bill was as close to depressed as I’ve ever seen him,” recalls Jeff Bridges, who played Nick Kagan, Winter Kills’ Candide. “But five days later he was on the phone: [Imitates Richert’s mad cackle.] ‘We’re going to Munich! We’re gonna make another movie and save Winter Kills!'”

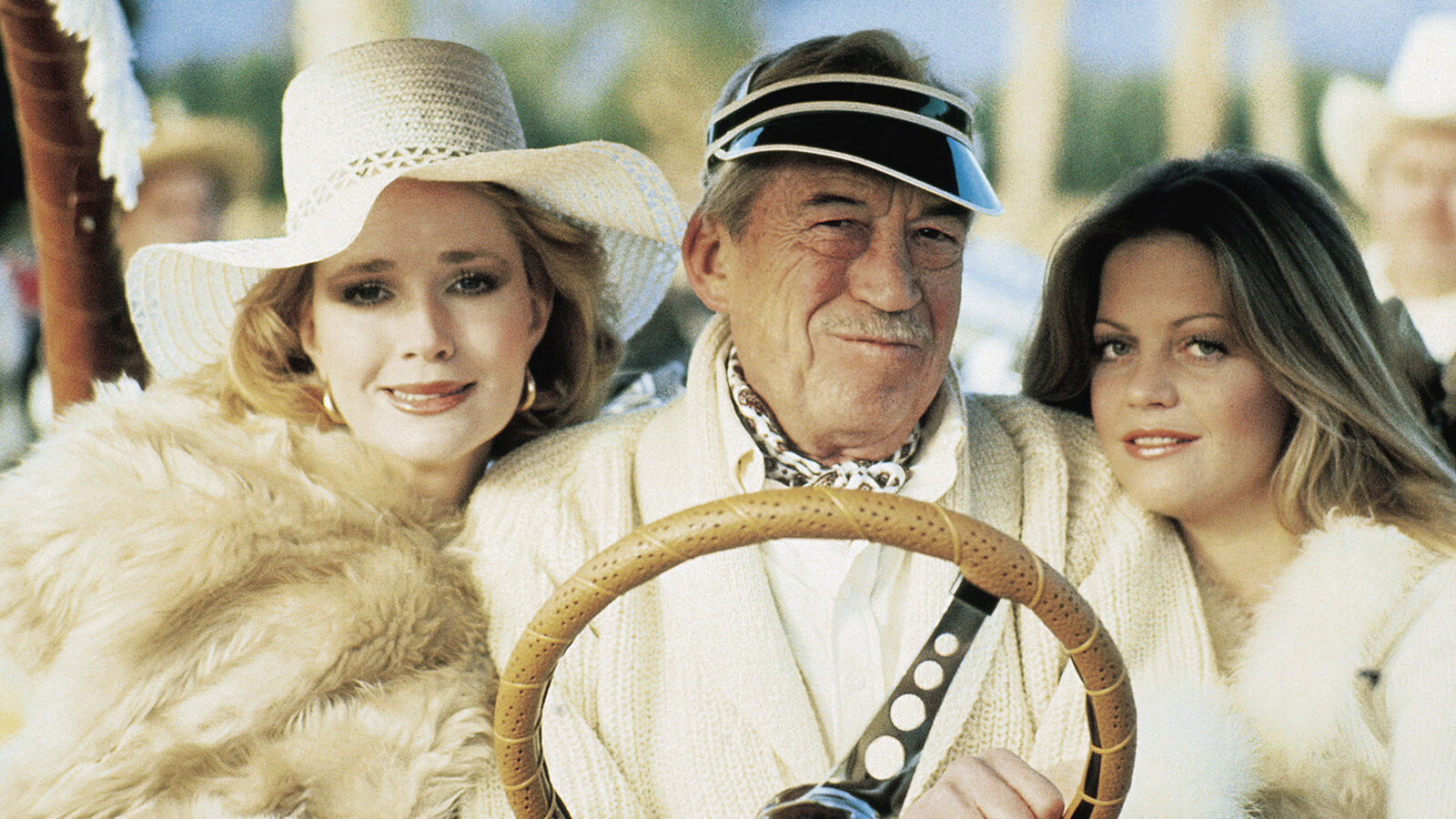

The other movie was Success (also known variously as American Success, The American Success Company, and Amsucco), and it was at more than an ocean’s remove from its predecessor. The $6.5 million Winter Kills teemed with plots, subplots, international locations, characters, and stars: Bridges, Perkins, John Huston, Richard Boone, Eli Wallach, Toshiro Mifune, Dorothy Malone, Sterling Hayden, Ralph Meeker, Tomas Milian, and an unbilled Elizabeth Taylor. Success, bankrolled to the tune of $3.7 million by West Germany’s Geria, never strayed beyond a few rooms in Munich and involved principally two characters: a pleasant schlemiel named Harry Flowers (Bridges) and his beautiful, narcissistic, rich-man’s daughter of a wife (Belinda Bauer, the Australian-born model who had also been featured opposite Bridges in Winter Kills). Ned Beatty had some choice scenes as Harry’s father-in-law and employer, the head of Amsucco (a credit card outfit), and there were sort of guest-star supporting roles for Bianca Jagger and Steven Keats. It’s an odd little movie—odd enough that Columbia, its American distributor, would never get around to releasing it. But when Richert brought it to Hollywood in 1978 and showed it to some people, it did the trick: he got his completion money for the year-and-a-half-stalled Winter Kills.

The rest should have been history. Winter Kills was a dazzling debut, aglow with the splendor of Old Hollywood— style production values, but, unlike most Seventies attempts at reviving the Old Hollywood grand manner, brisk with wit and narrative impetus. A hip sensibility was obviously in control, one that seized on Richard Condon’s farrago of sidereal, incestuous plotting and found in it a ripe metaphor for life after Watergate. But, again unlike most hip sensibilities at the time, Richert’s clearly relished the telling of a bright and stormy tale as much as any opportunity to express revisionist disenchantment with the way of the world. This guy would be great to have around.

Unfortunately, his film was around for about one week in the spring of 1979. The property had ended up with Avco Embassy, who apparently thought little of it. Rather than release it carefully, with an ad campaign that would alert audiences to its stellar riches and prepare them for its heady mixing of paranoia, black humor, and furtive poignancy, Avco used it as a filler to hold screens for their appointed summer biggie, the Susan Anton vehicle Goldengirl. It is small consolation that the public avoided Goldengirl like a rank sweatsock. Winter Kills went on the shelf, with only the occasional 16mm showing on campuses or in film societies to keep its memory alive.

***

For the past year or so, Richert has been scrambling to change that. In partnership with Claire Townsend, a former executive at United Artists and Fox with a reputation for helping provocative properties get off the ground, he has founded The Invisible Studio for the purpose of initiating new projects and salvaging his two distributor-abandoned movies. An initially hostile but ultimately felicitous encounter with Richard Mason, who at the time was Columbia’s West Coast manager, led to a precedent-setting accord whereby Richert would personally undertake distribution of Success. The studio having written off the film, Richert is not responsible for the negative costs on the movie. He can take his distribution expenses off the top of any revenue the film generates in the theaters where he manages to place it, and he and Columbia split fifty-fifty after that. He has a similar arrangement with Embassy (“Avco” having become merely another name on Hollywood’s celestial dustheap), though that one is complicated by the need to reimburse a number of players and artisans never paid for their contributions to Winter Kills.

This could mark the beginning of a new wave of recovery for the many “lost” films discarded by the system. It may also mean a new lease on life for Richert’s eminently promising writing-directing career. As of this writing, Success has opened in Los Angeles to mostly favorable, even generous, reviews, and is doing creditable business in one of the Beverly Center’s fourteen Cineplex auditoria. Winter Kills has begun its reissue life at the small, conscientiously programmed Pike Place Cinema in Seattle, where it is playing to mostly full, pleasurably rapt houses. It is now prominently billed as “Winter Kills: the Comedy” to help set up audiences for its multi-valenced qualities. Richert is still retooling Success, but Winter Kills stands as it did in 1979. As Richert puts it, “The film is the same—the time is different”: in the Reagan era, Winter Kills‘ masterful lunacy seems almost documentary.

***

William Richert is an exuberant Black Irish sort just crowding 40—so exuberant that he literally bounces off the walls of whatever enclosure he’s talking from, be it a hotel room or a restaurant booth. He’s an infectiously hilarious raconteur, and also one of the few filmmakers I’ve met who really hears the questions and comments put to him, and demonstrates in his response that he has understood and is capable of carrying the ideas further.

Once Winter Kills and Success are moving under their own steam, he hopes to start his third film, Will You Marry Me? This will be another comedy, about an Irishman who proposes to women when he gets drunk; eventually one of them has the bad grace to hold him to it after he’s sobered up. He plans to star in it himself, opposite Belinda Bauer.

The result may well be charming, though a comparison of Winter Kills and Success suggests that the small-scale, exclusively personal format may be fraught with some peril for Richert. Success is a fairy-tale screwball comedy in which the protagonist creates another persona for himself in order to shock his infantile wife into a more accessible maturity. In the course of redeeming her, he fundamentally changes his own idea of himself, becoming, among other things, a sexual athlete and a criminal. The film is a comedy of character, as Richert himself has observed, and the games he plays with identity and emotionality are more provocative than anything to be found in recent U.S. comedy-dramas of more solemn substance and less stylistic playfulness. But for all its intelligence and audacity, Success is uncomfortably more like a draft of an interesting movie than an achieved film. It keeps announcing themes for itself, and tends to play as a collection of motifs rather than an organic movie.

In Winter Kills, Richert’s talent thrives on the challenge of the original material (it’s arguable whether Condon has ever been better served by the movies), and on the big-budget opportunity for spectacle and proliferation. The large, veteran cast is at once launched on fullblown caricature and encouraged to become more hugely themselves than, in some cases, they have ever managed to be on screen before. The smallest bit parts are sharply honed: Robert Boyle as a whimsically solicitous hotel clerk; Billie Allen as a self-satisfied receptionist at National Magazine; Joe Ragno as a profane doorman who, with very little provocation, displays a baseball bat and a ferocious contempt for the rest of the known world (“Ya gimme the creeps, all o’ ya!”).

Above all, there is a keen and distinctive eye as hungry for beauty as for satire. When poor-little-rich-boy Nick Kegan wants to tell his cornpone Machiavelli of a father that he stinks, he has to climb onto a horse and gallop over canyon and mesa before shouting the challenge at the faraway family stronghold. The movement not only invokes the Western genre and the pioneer tradition Pa Kegan speaks of so lovingly (“The family unit—God bless you, God damn it!”), it enlarges on the spatial and spiritual parameters of the America that is so much the film’s subject. Still more exhilaratingly, it is an exultant explosion of aspiration on the director’s part, a reaching after grandeur to which his talent, again and again, proves equal. So let us have more films from William Richert, by all means. And let some of them be big ones.

Winter Kills (1979)

The following interview is compounded of several conversations held over a period of four months. Please note that ellipses are intended to convey pauses rather than excisions.

Where did Bill Richert come from?

Mary Iola McCormick and William John Richert, Sr., that’s where he came from. I was born in Miami during the war. My father was in the navy there.

He always wanted to be a sailor, but he became a C.P.A., so I guess he forced whatever romance he could out of life by marrying and remarrying my mother several times. And then when they would get separated, he’d follow her. So what happened was, I moved around the country, with this almost Eugene O’Neill—intense Irish mother, dreamer, and had this Teutonic father who found himself miscast in life. They never got together, so there was always this yearning for something that wasn’t, on his part. My mother was always finding us new surroundings, taking us to new towns. I’ve still no sense of where I live.

Your first credit was as a novelist. When did you write your book, Aren’t You Even Gonna Kiss Me Good-bye?

When I was 19. It was in the bookstores in 1966, when I was 23. It got wonderful reviews; I was compared to Hemingway, Joyce. The result was that immediately I wasn’t able to write another word. And I never have, not in a novel. I was too young, I didn’t know what I was doing and whether I could repeat it. When I read the book now, it makes me fond—I become very fond of that kid that I was. I remember trying to write the first paragraph of the next book over and over again, with The New York Times looking over my shoulder. I was too intimidated to perform.

That’s when I got the idea to make movies, because the reality was directly in front of you. You were forced into a discipline by technology. You had to show up! You couldn’t stay in bed and say, “What the fuck am I gonna do today? How am I gonna write that?” Forty people were waiting for you—or fifty! You had to be there and you had to perform.

And so you stepped into Richard Condon country—not Winter Kills yet, but rather the milieu of Presidents’ Daughters.

My first documentary [1969]. I got to interview daughters of the President the way Mike Todd used to get actors, by telling them that the other had already agreed to it. I used to go in and say, “How’s your old man?” I mean, here I was in the White House, I had conned my way into the White House! . . .

You weren’t the first.

. . . And I kept thinking, What right do I have to hear all these secrets of the life of a head of state, this state? I have interviews on tape where President Nixon’s daughters say John Kennedy stole the election, he was in cahoots with Mayor Daley, it was a criminal act, and their father wouldn’t prosecute because he didn’t want to throw the country into a civil war!

Where is that film?

I wish I knew. A little of it got onto 60 Minutes. They “lost” the rest.

Uh-huh. Then you were involved in Derby, Robert Kaylor’s film.

Kaylor was the cameraman.

I’ve always been curious exactly how Derby was done. When it came out in 1971 , some people insisted it was all utterly unstaged, the cameras just recorded. But that didn’t feel right to me: it was so shaped.

Of course it was shaped! How can you go into people’s bedrooms, they’ve just woken up in the morning, you put up the lights, have cameras, sound, and say it had no effect on this person’s life? Of course it had to be contrived.

Like: “How do you feel about your coach? What would you like to say to him? He’s gonna be there, you’re going there, we’re going to shoot it.” Then go in to the coach and say, “How do you feel about this guy? He’s gonna come and say this to you.” And the coach says, “He is?! Well hell!” And then you get these two guys together and film it, and it’s the truth. Whether or not it’s structured, what happens there is real to both those people.

Derby was a revelation, because it was so bizarre and so real. The unreality of real life—that’s what my movies have been about. Of course, at that time there was a fetish about “reality.”

Right. Easy Rider and the Cinemobile.

I came from that world of “reality.” I bought myself the ability to work on soundstages in Hollywood by working in shitty apartments where people always thought I was making porno films.

Derby led to First Position (1972). If I could make a movie about something hard-hitting and action-packed like the roller derby, then I wanted to show a movie about two people falling in love against the ballet world. I made a love story; and it was partly love story, partly ballet documentary. Have you seen it?

No, I’ve never had the opportunity. But I’ve seen the movies you went on to make with Ivan Passer.

I know you don’t like Law and Disorder [1974]. I understand that. But the thing about that kind of extremist humor, it has to be allowed to go all the way. The minute you equivocate, dilute it in any way, it doesn’t work. It’s like if you’re gonna make an ass of yourself at a dinner party, in the middle of a story, you can’t stop. You have to go all the way, like Hamlet, until everyone is completely offended. Then the cleansing effect takes place. But if you in any way get shy or embarrassed once you’re on that journey, you lose.

I loved working with Passer because he always liked the little characters. In fact, sometimes he gets lost in the little characters. And I do too. I like going with them. I like them.

That’s in his first movie, Intimate Lighting.

Wonderful! It’s all the black notes, all the black keys. There’s something haunting about him and his movies. Ivan is one of those guys that you keep thinking about and every time you do, you smile and it gets deeper. He’s like some… ancestor. There’s that melancholic, thoughtful, wise, abandoned quality in him. He’s the failed poet as filmmaker; that’s one of the things that’s so moving about him. It’s struggling for the right word or phrase that… you feel protective of him. And in doing so, you find strength of your own.

I’ve often wondered if he was comfortable yet with the American milieu and American speaking.

I don’t think he was. But I don’t know if I’m comfortable with it. I’m still looking for the American milieu!

I don’t know. We wrote a movie about Brooklyn subculture from a condominium in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. It was great. I used to spend whole afternoons wearing white clothes and talking with fishes. Especially one big grouper—I’d go see him every afternoon and dream about Brooklyn. Which is the best way to experience Brooklyn! There was a certain amount of artistic detachment from the very beginning of that movie. There were three of us [Kenneth Fishman was the third screenwriter], and I was never used to writing in a menage. By the time we got done with it we were just beginning to figure out how to work with each other, and then we had a screenplay, and we shot it. Whether it was successful or not. . . it was ready, we made it.

There was no question of readiness on the next Passer film. I had no idea you were involved in Crime and Passion [U.K.: An Ace Up My Sleeve (1975)], because there’s no screen credit for you.

I disappeared like vapor. I was vaporized the whole time I was there. I never came down from jet lag and alpine fever.

That film felt like one of those European co-productions that when the people got on location, they said, “Now, what was it we were going to do?”

Exactly what it was! [Cackles.] Ivan called me—he’s in Austria. “Beel! You most komm!” I komm. Ivan said, “If we do this screenplay, and we rewrite it every day, can they sue us?” And I said, “Ivan, they’ll kill us if we shoot the one they’ve given us!” I don’t think any of the actors had read it before the start of shooting. I arrived there, and Ivan showed me seven versions of it. I had just got off the plane. I remember struggling to keep my eyes open, struggling against it being five-in-the-morning, third-day-of-no-sleep, New York time. It was like being in intensive care and remembering nurses’ faces. There were these scripts lying next to me on the bed. And that was the beginning of that one.

That was a great education for me, writing to locations. To start at the middle of a mystery and write to both ends.

I like that movie. It’s not a “good movie”—you say you’ve never seen it—but the thing I like best about it was the way it started getting into fairy tale. It was St. George and the Dragon . . .

Yeah, right.

Except she was the Dragon Lady . . .

That’s right.

And that ending, with the magnate, the Bernhard Wicki character, out there frozen in the snow, just staring at the castle. And they think he’s on his way to kill them, but he’s dead out there, frozen in obsession.

Oh, I forgot about that! That’s great! [Cackle.] I think there’s a movie there; we just never got to make it.

I think maybe you have made it, in a way. What interests me now is that that’s also a side of you. The fairy-tale quality of much of Winter Kills, especially with regard to the family; and of course Success is fairy-tale screwball comedy, which also ends with its couple in curious suspension in a sort of castle.

I broke my connection with Ivan after that film. It was intense and it was long-lasting—we worked together for five years—but he was my teacher and it was time for me to move on. What he did was to help me find out who I was. And that’s what teachers are for. Somehow the intensity of that, of that time in my life and his life too, finding his legs in America—it was all over. I haven’t spoken to him since Omar Sharif’s place in Paris. And all the time I made Success and Winter Kills. I don’t know if he even saw those movies.

How did you find your legs for writing Winter Kills?

I was writing in an apartment overlooking Key Biscayne. I was with a group of people who were telling me—they said they did this—how they used to buy cocaine from Bebe Rebozo’s house. And I was looking out, and that was Nixon territory: that bridge that goes across, and down below was a boat that I could see from my window. Eventually, I met this girl and I wrote the last of the script on this boat called the Fantastic. There used to be sea cows at night making these strange noises. And I was writing Winter Kills, about this character [Jeff Bridges as Nick Kegan] who is lost in this world, this world of Coconut Grove. There were ships all night bringing drugs from all parts of South America. It was like a gold rush town. And I was meeting these guys in Panama hats. It wasn’t like a subculture, it was a whole culture. You know, Meyer Lansky is listed as one of the 400 richest men in the world by Forbes magazine. And you wonder. And Nixon is photographed playing golf with the heads of half the Mafia families. This excites a writer’s imagination!

Here I was, dealing with a book that I thought was totally bizarre and improbable when I first read it. And as I was writing, I said to [Robert] Sterling, the producer, “I’ll do it, but I want to make it a comedy.” He thought about it, and he said, “Well, you can try it that way.” I started writing, and then I realized that it was a kind of comedy already. I myself hadn’t caught on to a lot of Condon.

So I’m in this high-rise apartment building, trying to lick one of the most complex books I’ve ever read. It’s so complicated, to somehow make all that material blend easily from image to image. There’s a lot of language in the picture because, first of all, I love language, and Condon uses language as densely as John O’Hara. There are no conversations—it’s narrative dialogue.

But it’s not a “talky” picture.

No, it’s not. One of the things was to make this stuff come across in images. And one of the images is this immensely powerful man [Huston] striding to his son in a red bikini. That kind of incongruity, without saying anything, first of all pokes fun at a guy that big, and secondly tells ya how big the guy actually is, ’cause he doesn’t give a shit, and you have the feeling that he’d, like, you know, Lyndon Johnson, hold a press conference on the john. A certain kind of man. He doesn’t exist in corporations; he’s the guy who sold the corporations already. Most of the guys we associate with power are just petty bureaucrats. The original impulse gets buried much later by paperwork and expense accounts and ass-kissing. But the great fortunes in this country, by and large, were founded by people who were outlaws in one way or another.

Was the Huston casting inspired by Chinatown?

It had nothing to do with Chinatown. You see, I like to cast people who are real in the parts, forgetting that they’re actors. Jeff was right, he had the qualities for Nick; I knew that from seeing Rancho Deluxe. And Huston: Huston is one of the most powerful men around. I mean the way he deals with his life, the kind of movies he makes—his sheer dimension as a person who is alive in his time, and has enjoyed every second of it. He was there. He was there with the great men, because he was one of them. For him to play that character is just fitting. He’s an actor, but he’s also himself.

Something else, it was a part that had a lot to do with language. Huston understands language, the scope and power of it. He relishes language. So those lines were things that he enjoyed. The part gave him room to move. He wasn’t a simple villain; he was a highly complex, society-created and promoted monster.

When I see Winter Kills now, I gotta admit, I almost can’t imagine I had the fuckin’ balls to write that stuff, let alone shoot it. It’s very elemental. It’s sacred territory being walked on. It’s fathers and sons. All this Condon plot about assassinations and wealth and power and America, and it comes down to this son saying, “Don’t kill me, father.” And the father says, “I want to live longer.” But then when he realizes he can’t live longer, he gives the kid a tip!

Winter Kills feels as if it’s global in its reference, yet it suddenly occurred to me about the third time I watched it: They could have shot this in one city block.

That’s what we did, practically. Cuba was the backlot; there was some stuff in Philadelphia and New York, and the location for Rockrimmon [the Kegans’ Western ranch] at Furnace Creek Inn in Death Valley. But otherwise it was shot in the soundstages in Hollywood.

What an opportunity it was for me to go to Hollywood to shoot my first feature. You know, I had my MasterCharge card, which was just about to expire. I was staying at the Beverly Wilshire, which is a good address. And if I didn’t get those actors that I went out to get, I wouldn’t have been able . . . The guys in New York were not generous. The producers would not have paid my hotel bill and they’d have gone after another director.

I mean, who was I? When I went back to the producers I had agreements from Jeff Bridges, John Huston, Elizabeth Taylor, and then Anthony Perkins, to be in a film to be directed by William Richert. And then I was in as director. I mean, there I was—I got them that. What were they gonna do?

The film is all-star at every level—except, at the time, the writer-director level.

I didn’t know how to look through the viewfinder of the Panavision camera! When I first looked the shutter was closed, and I didn’t know whether to say “I can’t see anything” or not. I just had to rely on the fact that it was all working. I could see the composition was all right. Later on, I realized that part of directing—it’s all seeing and selecting. You say, “Here, put the camera here and photograph that,” and it always comes out all right. I don’t know how it does.

Well, at some level you’ve got to know how, because a lot of people can’t get it. In Winter Kills, the dialogue is great, the detailing is sharp, it makes its points but doesn’t stop and say, “Look at me, aren’t I a great detail?” The movie moves and looks terrific.

You see, in life and in my movies, I don’t keep anything around. I feel motion. I think it’s a kind of restlessness. The lingering approach to something, I’m not comfortable with. I’m impatient. That’s why I write fast. I like to direct that way too; I send the crew home sometimes at four-thirty, five o’clock—which most people don’t do—because I lose patience, I try to do as few takes as possible, to keep that tension; and I think that tension shows up in the film.

How did you hit on Vilmos Zsigmond?

Well, I’d seen Deliverance. . .

But Winter Kills is very different from anything he had done. It doesn’t have the solarizing, the flashing, the soft poetic touch of the Altman films. It’s bright, epic. And he does it magnificently.

He becomes very close to the director he works with. I remember describing all the effects I wanted, in my house. He came over and I told him and he said, “Ohooooo, you want Picasso! You think you’re Picasso!” and I said, “Oh yes, absolutely, let’s make it like we’re all Picasso.” He had this beard then; he’s like a tall leprechaun.

Anyway, see, Vilmos has in his work an absolute clarity. It’s almost like the way Matisse once described Los Angeles, the light of it; everything was so sharply in focus. (God knows what’s happened since Matisse saw the light in Los Angeles!) But he’s clear; his frames are steady and precise. That’s what I like. Forgetting all the effects and stuff, there’s a solidness about his work. An absolute, craftsmanlike clarity. Above all, I wanted my first movie in Hollywood to have strength, what I always thought was the best of Hollywood: clear. Auguste Renan once wrote, “Mankind, when in possession of a clear idea, has never chosen to cloak it in symbols.” Winter Kills is so complex, but any of its pieces is absolutely simple.

That clarity you talk about on Zsigmond’s part is essential to Winter Kills, or anything like Winter Kills, because if you’ve got all this complexity, these situations always ready to slide into hallucination, at a conceptual level, you’ve got to have this clarity at a stylistic level. Another aspect of that: you had Hitchcock’s main production designer.

Robert Boyle, who’s an amazing man. He’s a wizard. Full of ideas. I put him in the picture; he’s the desk clerk.

You gave him one of the biggest laugh lines in the picture. Or so he makes it.

It’s a total sleight of hand, what he does with production design. He’s got boundless energy. He’s, you know, white-capped hair; I once asked him how old he was, and he refused to tell me. And I realized what an absurd question it was, to ask him to limit himself with an age, a number.

The main qualities of these old-timers was their, first of all, limitless patience with a director. And the second thing, he used to say I was showing him things, which means that he was always able to show me things; there was never a ceiling on our possibilities. It was always “There’s a whole other way to do this that I always wanted to try.” There was a quality about the men who worked on Winter Kills, that I could dream whatever I wanted to. I never felt constrained by money. (Of course, I didn’t know that we didn’t have any. That’s a help.)

I remember when we were shooting in Philadelphia. I had a hundred-and-four fever. We were shooting on JFK Plaza, and that’s when I got the idea about the horses coming around, and the riderless horse. It all came from this place. One of the things about doing documentary that helped me learn was to draw from a place its own character, to allow the suggestion of that. To me, when JFK was assassinated, and then that riderless horse came in the funeral cortege, you lost your breath.

You lose your breath at that point in the film, too. It’s been a grabby movie, but at that moment you can feel it lift onto another plane entirely. The dislocation seems all the greater because we’ve had a lot of low comedy with Brad Dexter as the police captain, always turning in the wrong direction and pounding on doors that are unlocked. And then the surrealism of the horses is followed on by the ways the guys get to be dead in the car . . .

Yeeaaahhhhhhh.

. . . and reality starts shifting all around Bridges.

Finally there ought to be a way to come to grips with what happened in that generation. Bob Boyle used to say one ‘Ah shit’ is worth a dozen ‘Attaboys.’ I don’t mean to be facetious. We went through some heavy stuff in that time; one thing happened and then we were hit by another. The tragedies of losing our leaders like that: just when we were beginning to grow, they were shot down. Stupidly—not for any apparent immediate gain. It wasn’t like a new man killed the king and became king. It was some absurd thing. How do you account for that? How do you incorporate it into your frame of reference? How do you expiate that? Where’s the metaphors for that?

Did you pick Maurice Jarre?

Yes.

The reason I ask is that we associate Jarre with soupy Doctor Zhivago projects, and it seems strange for a shrewd cookie like you to say, “I want Maurice Jarre.” And yet he contributes a great deal to the film. There’s a pull in there: against the hipness of the subject and attitude, you get this yearning romantic presence in the music—which I feel is as authentically you as the other side. Of course, you used him again on Success.

The thing is, in Winter Kills I wanted the echo of history. Past kings, past triumphs, and great romance. I mean, the fact that this guy [Bridges’ character] communicates mainly to an answering machine to reach the woman he loves—that relationship is no less real to him than Omar’s with what’s-her-name. He has this great love and I wanted to show that, in spite of the hipness of where we are, we still have ancient feelings. And Jarre, he’s [mimics music from Lawrence of Arabia]. I wanted that size. I wanted this movie to be big. And music can help you with that a lot. Huston’s a king. And he’s trying to impress his son. And in the end his son kills him, by not recognizing the extent of his father’s power. By not recognizing how small he is, the guy ends up destroying the whole system, just because he doesn’t know the dimensions of it.

Winter Kills had a brief release in 1979. Success, your second film . . .

But first completed. I made it when Winter Kills was shut down.

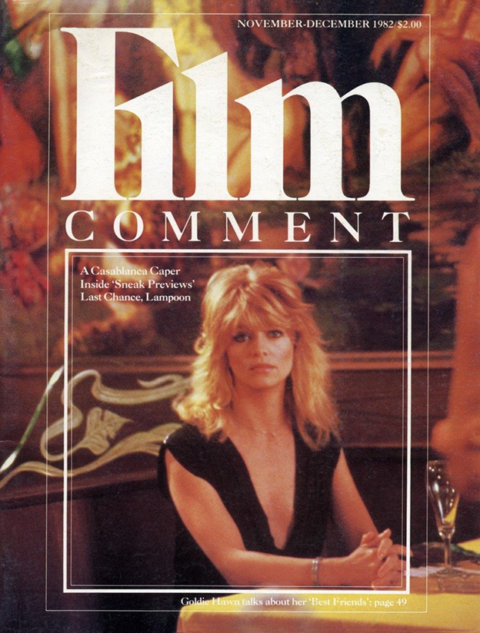

Success has never been released at all, till late August of this year, and so far only in L.A. Like Winter Kills before it, it’s been generally well reviewed.

Very nice reviews, very enthusiastic. Except for Charles Champlin. He’s not even the reviewer any more at that paper, but he just hated the film.

It was like being shot in the back. The guy knew I was getting up—I was already knocked down. It was like getting up from being hit by a sportscar and this diesel ran over me from the other side. He told the press agent, “I loathe that guy’s work.” He loathed my work? LOATHED . . . loooaatthhed . . . [Tries out several more pronunciations.] Then I realized that I must be a heavyweight, ’cause that guy’s the biggest guy in this part of town, so there must be something in there that affects him. This movie, it’s from the dark side of consciousness. It’s the half of the world that’s in moonlight. Champlin—he’s screaming at moonlight!

Do you think you’ll take any flak from women’s groups over the characterization of the wife [Belinda Bauer]?

The most liberated women I know know that there are women like that, and they laugh at that situation the way I do. Isak Dinesen said, “When women have got done with the business of being women, there’s nothing more formidable on earth.”

Has Belinda Bauer been in any other films besides yours?

She did two other movies; they’re about to come out. One was called Dorian Gray, with a female Dorian Gray. I don’t know what it comes out like, but it’s a great idea. The other is The Time Riders. I think she’s a star. The definition of a star is somebody I’d have wanted to marry when I was 10.

Is she foreign? That voice of hers is unique, I can’t even make up my mind whether she has an accent or not.

She’s Australian. She’s lived all over the world. She decided she wanted to be an actress. She’d had a whole life by the time she was 24. She’d been with amazing men, in amazing countries. She lived in India for a long time. Hong Kong. She became a top model and then an actress. She’d already done most of the things people do after they become famous.

I’ve seen Success three times now, and it’s been a different film every time. First there was the Columbia version, which I was interested in, but it felt like two-thirds of a movie. Then you screened a cut of your own one afternoon in Seattle; it had a voiceover by Jeff Bridges and seemed to play better. Now the version on public view in Los Angeles, which also has the voiceover, but . . .

See, the way I make movies—I don’t know how I make movies, but there’s always characters and scenes awry. The only thing that matters about the effect of anything is how it affects you. It doesn’t matter if it’s linear or “well constructed” in the traditional sense. I say, “I’ll show you this and then this and then this. We’ll see how this relates to that.” Because in life, things are not linear. There’s past, present, and future, all at the same time. We’re having this dinner conversation, you’re perfectly aware of where you’ve been this afternoon, you know where you’re going next. Movies can be like that.

As simple as this picture is—just three characters, a few locations—it can be on so many levels at once. It’s his masculinity, that’s one level, which he tries to build up by working with disguises—and that’s his femininity, because disguise, makeup, to dress up, is a feminine trait. And there’s his wife’s role, daddy’s little girl and her mirror and fairy wings. And the hooker whose hookerishness is a disguise for what’s behind that. The hooker is full of love, really, and the wife isn’t full of . . . anything . . . until he awakens something in her. And did he awaken it, did he put it there or bring it out of her? Was she there before or did she begin with him? Was he anybody before he met her? Where does potential become real?

When I make a movie and people try to describe it to each other, they all describe something different. The story—it isn’t the story. The story isn’t what’s described. What matters is what happens to you while you’re watching.

What did Larry Cohen have to do with Success? He shares the screenplay credit, and there’s a panel that reads “A William Richert—Larry Cohen Film.”

Larry Cohen is a total asshole. He did nothing on Success, nothing. He wrote a story about a couple, a pair of harpies, living in Paris. There was a detective in it, and the guy disguised himself. That’s the only aspect in common with my film. He wasn’t around, he took no part. In private, he said he didn’t want to be associated with such a piece of shit; but publicly, he kept the writing credit and demanded to share in the “film of” credit.

Did you always intend that there would be narration?

No, I never intended it, at first. The guy who wrote it is a friend of mine, Rick Johnston. He’s in advertising in New York. He had seen Winter Kills and said, “Bill, this is a great movie, but you have to position it for people.” And he came up with this line: “Once in a while a picture comes along which truly expresses the spirit of the American family!”

To an extent the narration adds a dimension to Success, but some of the lines are redundant. They tell us things we can see anyway.

Yeah, I know. I’ve cut them out. I think you’re remembering them more from the earlier version than from what you saw the other night.

That’s true. But there are still some. Like, he says, “I was the kind of guy who was afraid to leave his house in the morning because of a little dog.” And then we see the scene, and he’s the kind of guy who’s afraid to leave his house because of a dog. Of course, you have a practical problem when you use narration. Once you use the device, you have to, well, check in with it every once in a while, have the guy say something, just to keep the device operative.

But that line’s okay, because it’s not just telling us what we can see anyway, it’s also telling us that the guy does know this about himself. And he did still go out every morning and face that dog. He was brave enough to do that every morning. He’s afraid and he’s courageous.

Another friend of mine, an Englishman, saw the film and said, “It’s a Victorian tragedy. This man’s madly in love with his wife and this woman is insane.” I said, “I know, isn’t it wonderful?!” He doesn’t ask her to be what she isn’t. He realizes that this is all she is and he loves her anyway, and he stays with her.

You’ve said that you never got to shoot the beginning and the end of Winter Kills. Would you care to indicate what that was to be?

We start in outer space. It’s like an angel moving toward Earth. And he sees this very tiny planet—

Some Angry Angel?

What?

Some Angry Angel—it’s the title of another Condon book.

No shit? That’s great! Did I tell you about Condon when he came out of the screening of Winter Kills? He says—he’s a big guy, and he stutters: “Y-Y-Y-You know the d-d-difference between y-y-y-you and me? It’s that y-y-you like p-p-p-people and I-I-I-I don’t!” I’ve come to realize that I agree with him.

Anyway, we come down into this storm on Earth, and there’s this ship in danger of sinking. This young aristocrat is there with this girl, who’s very interested in him but he can’t be pried away from the phone—even though he’s only talking to an answering machine. Which to me is this disconnection in our society: the guy thinks he’s in love, but he’s in love with a voice.

Now, at the end Jeff takes over the organization, “the family,” and he wants to reveal “the truth.” And all through the organization guys are blowing their brains out. Jeff goes outside, and the woman with the kid on the bicycle goes by. And what happens—it doesn’t matter what happens to him, because now he’s not who he was anymore. He’s dead anyway.

Well . . . I wouldn’t like to part with the ending that’s there now.

No, and I think maybe I like it, too, because it’s not as cold. I mean, even if the guy’s just talking to a voice, he still remembers he was capable of love.

Somehow, I know that, whatever my movies are, I’m just starting. I’m still growing, I’m growing out of this shit. This is my humus. (Not hubris, humus. And they’re very similar, because you don’t know whether you’re in the shit or the hubris! [Cackles.]) I think I’m climbing out of this, and I’m taking my movies with me, because I’m the only one left with them. But as I get them shown, and people respond to them, it’s surprising. I’m finding my mates. I’m learning to “rely on the kindness of strangers.” Maybe there’s more of me out there after all.