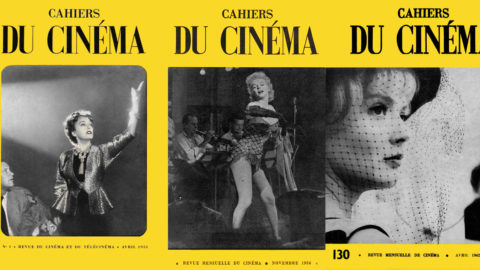

Why Cahiers Still Matters

A couple of months ago I was in Paris to record interviews for the BBC with several film critics about the 50th anniversary of Cahiers du Cinéma. I left with the impression that the magazine has, in a curious way, become a victim of its own success. Once a self-proclaimed “revue de combat,” a forum for contestation and a home for mavericks and radicals, Cahiers is now a fully integrated part of the French cultural establishment. This impression is lent weight by the fact that the magazine was bought up, in October 2000, by Le Monde publishing group, an arrangement that the editor, Charles Tesson, told me ensures the financial security of Cahiers as well as its editorial independence. Frédéric Bonnaud, of the weekly Les Inrockuptibles, described the perception that exists in France of a “triangulation” of film-critical influence between Cahiers, Le Monde, and the left-leaning daily Libération, in which the tradition of cinephile-criticism inaugurated by Cahiers continues. It’s a triangulation that should be extended to include the other nodal point of Les Inrockuptibles itself.

While the influence of Cahiers has grown in France, to the extent that one might say it has become semi-institutionalized (e.g., one of its mainstay critics in the Eighties and Nineties, Alain Bergala, was recently charged by the Ministry of Culture to oversee a program of film education), its influence abroad has waned. Why? The “exportability” of Cahiers’ critical ideas was always dependent on two things: film distribution and academic receptiveness. Dave Kehr describes how the Nouvelle Vague was a truly global phenomenon that served to disseminate many of the ideas the Nouvelle Vague directors had practiced as critics—auteur study and mise-en-scène-based criticism. In 1963, when Jacques Rivette replaced Eric Rohmer as editor, the magazine became more open to the intellectual currents of the time—structuralism and literary modernism, in particular. This intellectual openness remained a feature of the magazine throughout the Sixties and Seventies, with Cahiers writers frequently engaging with the work of heavyweights such as Althusser, Lacan, and Foucault. In this respect, Cahiers’ intellectual history was part of an academic revolution taking place in the humanities. But in the Eighties and Nineties, the dialogue across continents and disciplines appeared to dry up. Much of this has to do with the institutionalization of Film Studies as an academic discipline. Founded on Cahiers’ groundbreaking work in the Fifties and Sixties, Film Studies has since become a satellite of Cultural Studies, an academic discipline that doesn’t exist in France, where film criticism remains informed by the understanding that a film’s form is indissoluble from its content.

Cahiers virtually invented—then reinvented—some of the major tools of journalistic film criticism. The format of the interview, for example, has had several leases on life. Truffaut’s interviews with Hitchcock are exemplary of a kind of first-phase cinephilic oral history. The auto-critical, multi-voiced collective analyses that Cahiers undertook in the early Seventies, most notably on Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln, Renoir’s La Vie est à nous and Sternberg’s Morocco, informed the then-nascent cine-structuralism of Screen magazine in the U.K.

Is Cahiers a victim of its own success, then? A hostage of its own authority? From an international perspective, indisputably. The downside of this is that the magazine’s critical initiatives of the past 20 years remain largely untranslated and inaccessible to English-language readers. The most glaring example of this kind of academic quarantine is the near invisibility of the work of Serge Daney, the most important film critic of his generation. But, in addition, the major work undertaken in the Eighties on cinema and painting by critics such as Pascal Bonitzer and Alain Bergala barely registers. Equally, the magazine’s recent openness to experimental film, digital aesthetics, and the place of the moving image in the art gallery, in response to investigations led by Raymond Bellour (non-Cahiers writer) that go back to the early Nineties, also have yet to be translated. The irony is that Cahiers—which has a publishing imprint with an extensive catalogue—translated the American philosopher Stanley Cavell’s book The Pursuit of Happiness: Hollywood and the Comedy of Remarriage in 1993.

Just as the Anglo-American academic channels have narrowed, so, too, has international film distribution become increasingly constricted. Those Cahiers alumni who turned to filmmaking since the Seventies—André Téchiné, Olivier Assayas, and Pascal Bonitzer, to name only a few—inevitably find that, abroad, their alma mater is still seen in terms set by the debates of the Sixties. There’s a lot of catching up to do.