Where Are We with Bergman?

Ingmar Bergman would have turned 100 on July 14, 2018. His final feature, Saraband, was released more than a decade ago, though he had decided to stop making films in 1982. Putting these dates side by side allows us to consider his body of work through the lens of time, posterity, and the history of cinema. You could ask what Bergman’s work has to tell us today, but you could just as well reverse the question and ask what our relationship to his films says about us.

Let’s speed through Bergman’s status in our cultural pantheon. He has achieved a dizzying level of recognition. We have never stopped watching his roughly 40 films, which are accessible in many formats and languages. Among his abundant and diverse filmography audiences can make their own selections and will always find masterpieces matching their sensibilities. His 1987 autobiography The Magic Lantern is a striking literary feat; a rich variety of books have been devoted to his life and films; and there is a foundation dedicated to his memory that preserves his home, personal belongings, and environment so that artists from all over the world can come seek inspiration from his model and aura and enter into dialogue with his ghost.

One could even add that Bergman has the privilege—or the curse—of having crystallized in the collective imagination as an archetype of the filmmaker: introspective, chatty, misanthropic, and also a kind of Bluebeard who left little space between life and art in his relationship with his actresses. In that, he is irreducibly connected to his time. In thinking about Bergman in the present tense, we also question our relationship to his era.

Like most great artists, Bergman is both singular and multiple. He was by turns a young screenwriter for Alf Sjöberg, a novice director influenced by French poetic realism, an early disciple of Italian neorealism, and by the age of 40, an internationally recognized artist whose films had rightly or wrongly left their mark on their era and the history of cinema. The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, Smiles of a Summer Night all came before he was recognized as one of the pioneers and key figures of the cinematic modernism of the early ’60s, and he pushed further with every film, to the peaks of Persona, Scenes from a Marriage, and Fanny and Alexander.

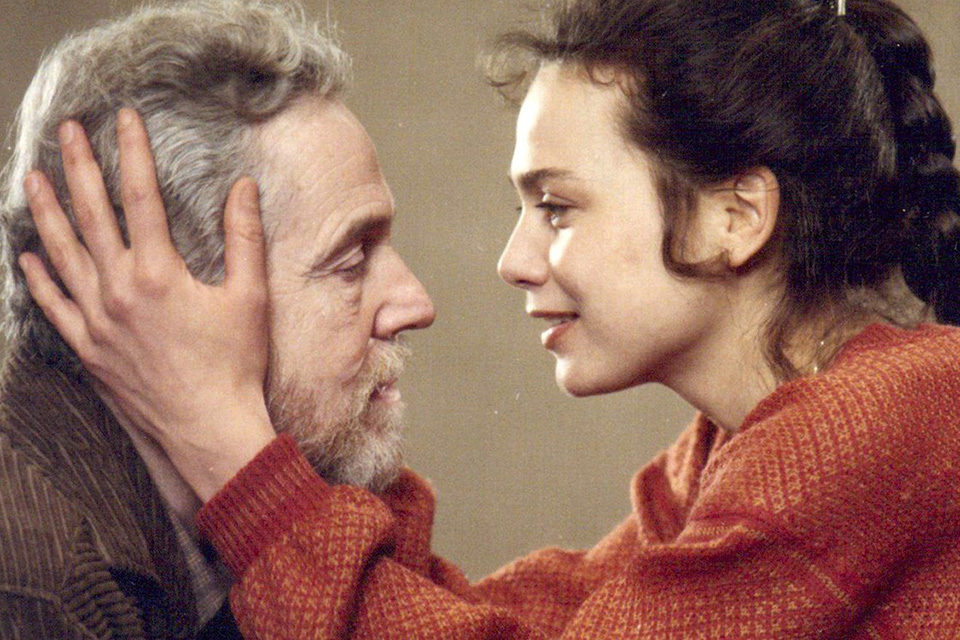

Fanny and Alexander

And yet this is only one of the lives of Ingmar Bergman, a product of the long history of Swedish cinema who never ceased returning to the model of Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Carriage. There is yet another Bergman, one haunted by the figure of August Strindberg. This Bergman grew out of a different modernity, that of the audacious, tortured, and pessimistic interiority of Scandinavian theater from the late 19th century. Which version of Strindberg did Bergman chase his whole life? Was it the cruel and often misogynistic observer who wrote The Dance of Death? The hallucinating author of Inferno who wandered through Paris on the edge of madness? The playwright fascinated by his actresses Siri Von Hessen and Harriet Bosse, to whom he wrote unforgettable letters? Or perhaps the underappreciated painter, a precursor of abstraction with his tormented seascapes, experimenting on the fringes of the art of his time with his Celestographies?

One must first consider Bergman as a man of the theater, like Fassbinder, whose relationship to film and the film image and its aesthetic is an extension of the relationship to the spoken word, writing, and the stage. And while his films participate in and determine the history of modern cinema, what inspires them comes from a much earlier place. In this, Bergman is in dialogue with the peaks of contemporary theater, and if he had never made a single film, he would still be one of the greatest dramatists of his time.

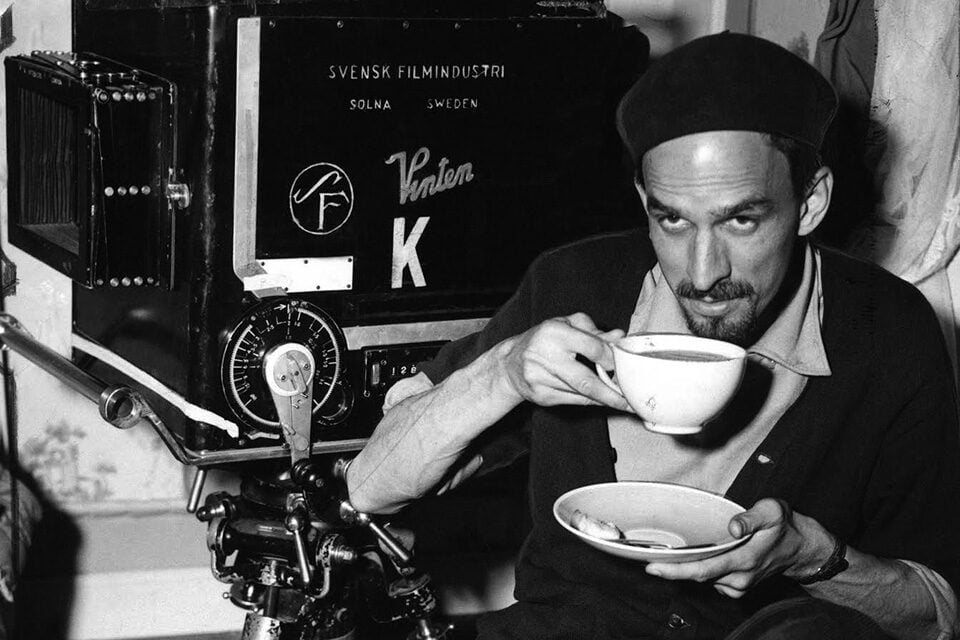

My favorite image of Bergman is found in the 16mm films documenting his shoots in the ’60s: the weather is nice and he is cheerful, even childlike. At the time, he was running the Malmö City Theatre, directing one play after another all season long. When the theater would close for the summer, he would bring together his troupe to make a film in which cinema, vacation, and love seemed to combine in a utopia that may be the key to the duality that defines his work. The underside was depression, which would later be the source of some of his masterpieces.

Bergman’s schooling in cinema is not particularly relevant. His first films—in which one is perfectly entitled to be interested—are very much in the spirit of their time, immersed in the existential gloominess of the postwar years. What is more interesting is the way Bergman struggled to get rid of his influences, to become himself by leaving behind cinema’s old-fashioned baggage, which led him on the path to a luminous and timeless present, that of modern syntax.

This connection to dramaturgy is absent in the French New Wave, which is founded on that idiosyncratic relationship to cinema known as cinephilia. However, it is omnipresent in England, where the British New Wave was written by Harold Pinter, John Osborne, Alan Sillitoe, and Keith Waterhouse. But Bergman’s singularity is in what differentiates him from the English: in his work, the most important thing is that the spoken word is embodied. The relationship to the performer is not through the assertion of the text but in its transcendence. This alchemy is the deepest and most mysterious thing at work in cinema, its very essence. And it is the discovery of this particular fragile and ephemeral truth on the faces of his actors and actresses that defines the most intimate, most secret space in cinema—one that Bergman tirelessly explored, pushing beyond words. Thus we could envision an arc from cinema to writing, and finally to embodiment surpassing both.

But what happened in 1982, when a 64-year-old Bergman announced that Fanny and Alexander would be his last film? That can be interpreted in several ways. You can consider that this film—longer, more ambitious, and more novelistic than all the others—was supposed to be his crowning achievement. Or else that Bergman himself wanted to produce the only legitimate commentary on his oeuvre, since in 1992 he published Images, his artistic autobiography, which was supposed to close the case once and for all. One could also have chosen not to believe him, as was my case: I imagined that Bergman wouldn’t keep his word, like Jean Racine, who after 12 years of silence returned to the theater with two masterpieces, Esther and Athalie. Indeed, Bergman soon contradicted himself. In 1984, he directed After the Rehearsal for television—the film was distributed in theaters against his will, and to prevent that from happening, he never shot on celluloid again—and then regularly continued producing important works on video, all of which have a fully legitimate place in his filmography. This extended to his late masterpiece Saraband, made in 2003 when Bergman was 85 and shot not merely on video but on HD—and, incidentally, the first feature film projected digitally in Paris.

What can be observed is that starting with After the Rehearsal, Bergman stakes a claim to the “small form,” like Racine when he wrote Esther and Athalie for the pupils of the Saint-Cyr boarding school for girls. These new films were absent from movie-theater screens, film festivals, and the radars of film critics and historians, to instead hide in the flow of images. Who at the time paid attention to The Blessed Ones (1986), Sista Skriket / The Last Gasp (1995), or In the Presence of a Clown (1997), to name only the most notable? At this point, Bergman was devoted to a cinema liberated from cinema. He was done with visibility and issues of economic success or failure. No explanations were owed, either to journalists or the audience, or even to the present, from which he moved further and further away to enter the light-soaked, otherworldly eternity of Saraband.

On the set of Saraband. Credit: Bengt Wanselius

Yet Bergman was never more active than during his years of “retirement.” He directed an ever-increasing number of productions at the Royal Dramatic Theatre, getting up to two or three a year; published his memoirs and The Best Intentions, a novel he then adapted into a miniseries directed by Bille August (and which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes); and wrote screenplays for his son Daniel and Liv Ullmann. He regularly granted long interviews (including to me, in 1991), increasingly haunted with concern over his legacy, as if he was making his final pronouncements for future generations.

What changed? Why the abrupt shift? And what’s missing? If not the eroticization of the relationship to bodies, to light, to his actresses, that limpidity that always defined his films, in part due to his collaboration with Sven Nykvist, which began with Sawdust and Tinsel in 1953 and came to a close over 30 years later with After the Rehearsal. The sensuality of the image in Bergman is the secret link between desire and his films.

Could it be that this desire left him? To be reformulated as something else? Something that would allow a withdrawal into himself, through the introspective movement of writing, the humility of a chamber cinema, concealed, deceptively inconsequential, detached from the world and even more so from cinema, but inhabited only by what is most important: an inner necessity. What if in the twilight of his life Bergman wanted to be a different artist? What if he wanted to be something other than Bergman? Or else return in a severe mode to the clarity of his youth, being a man of the theater sovereignly making films whenever he felt the urge. But he was now concerned with the literary work that had always haunted him and for which he never found the time off or the peace, for cinema and the powerful desires it sets off never left him the space or leisure. At this point in his life, Berg-man became aware that his days were numbered and that there were too many things left to do to allow film to remain the focus of his work. And so he chose to shift its center of gravity.

Bergman occupies a unique place in French cinema. Though an icon of the New Wave, admired both by Godard and Truffaut, it is to the next generation that he would serve as a magnetic north. Indeed, the only thing Philippe Garrel, André Téchiné, Benoît Jacquot, and Jacques Doillon have in common, aside from being deprived of a dialogue with their French elders little interested in passing on their experience, is that in the ’70s and ’80s, after the years of political radicalism, they went looking to Bergman for the tools that would allow them to reconstruct a relationship not with novelistic, non-Brechtian narrative but with embodiment, at the intersection between the character and the actress or actor—a cinema that scrutinizes humanity by scrutinizing the mysteries faces reveal.

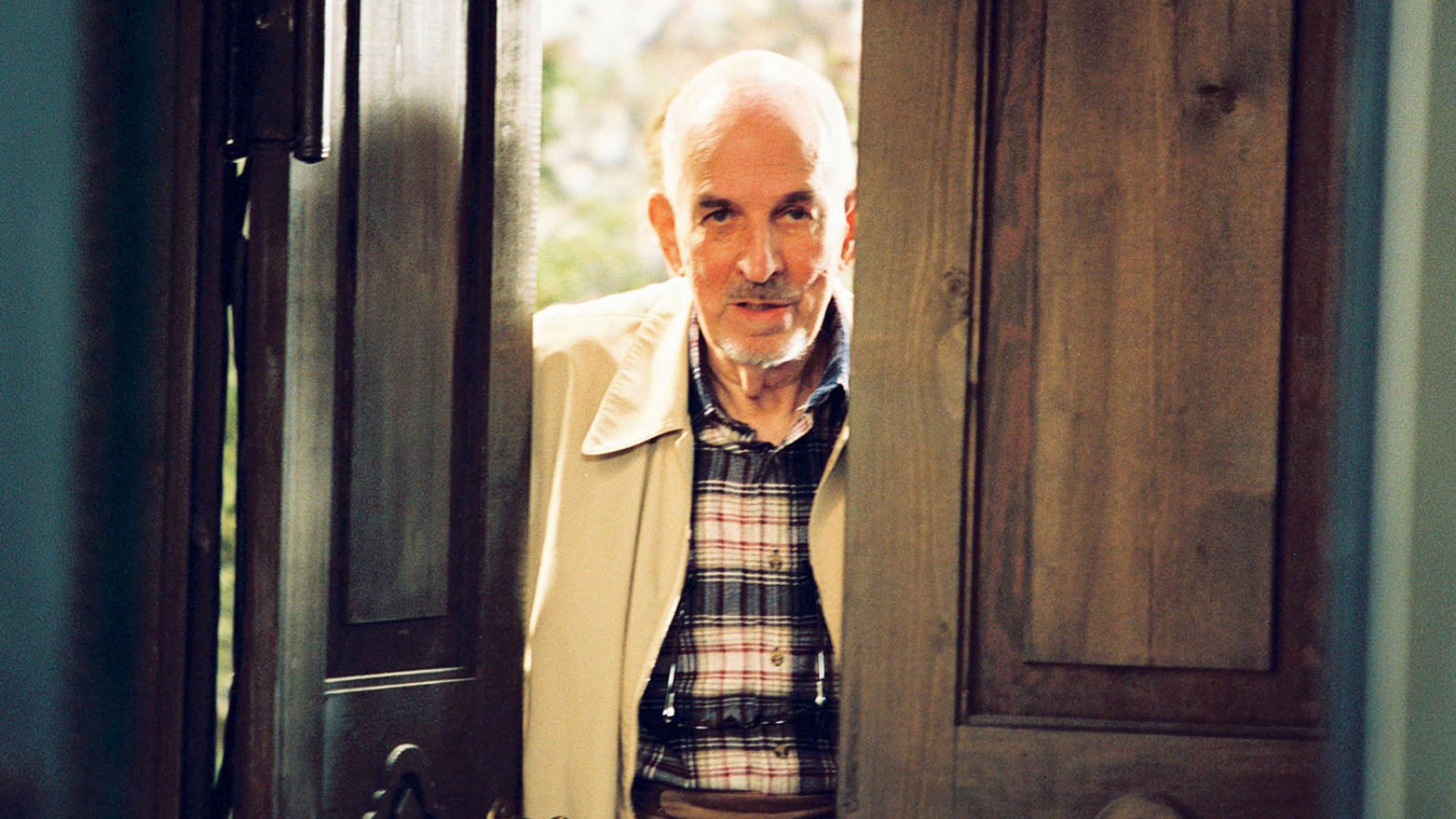

After the Rehearsal

But what exactly can we do with Bergman today? He who X-rayed relationships between men and women—more so from the woman’s perspective, one should add—and who used his camera to explore the paths opened by psychoanalysis and what it tells us about the machinery of our subconscious, its language, its silences, too, and the ways of the invisible? Are we still interested in the mysteries of the human being, the turmoil of faith, the torments of love, and the dialectic of the couple, which inspired the greatest filmmakers to make some of the deepest works of art of the last century, or are we over that? Has the world changed so much? Where are we at with psychoanalysis? Where are we at with time, as the poet Arthur Cravan asked?

It seems to me that there is a lack of psychoanalysis in cinema today, just as there is a lack of Bergman and a lack of relationship to time, or of what is built with time, the way Bergman’s body of work was built with time, for example. Yet cinema, which examines the soul through the features of its performers and records both silence and speech, both the visible and the invisible, has always been the best path to approach the chasms of the unconscious and the part of us that irreducibly escapes us. The truth is that we’ve always known this; Bergman wasn’t the first to discover it. Yet one step at a time, his path led him to understand and choose as his subject what is most precious in the ontology of cinema: its capacity to represent the complexity of human experience, to face its contradictions and ambivalences, to look at what is simultaneously destructive and full of hope, transcendent and maddeningly trivial in humanity. Like Bresson, Bergman turned his back on faith, which was no simple matter. Bergman did not like family, he had a terribly ambivalent relationship to his own children, and he didn’t much like men either. Does this sincerity of a tormented soul make him a bad person or our brother? Ultimately, he only believed in one thing: women as salvation.

It’s hard for me to find Bergman in contemporary cinema. Or rather, I see his absence as a terrible void. We move away from Bergman when we move away from our dark side and the necessity to face it. We move away from psychoanalysis, as is the case today, both in society and on screen, not because we have something to hide but because we don’t want to know or see what we have to hide.

Once this time has passed and we are again interested in questions and doubts in our exploration of humanity through cinema rather than in certainties, preconceptions, and social stereotypes, Bergman’s work will still be there to guide us.

Translation by Nicholas Elliott

Olivier Assayas is the director of Personal Shopper and the forthcoming Non-Fiction, among other films. This article was originally written on the occasion of the Ingmar Bergman retrospective at the Festival International du Film de La Rochelle.