What a Fool Believes

Neither of them wanted it to turn out like this. I refer, of course, to the divorce that (title notwithstanding) is the heart of the story in Marriage Story. Noah Baumbach’s latest film opens with a feint: a voiceover going through the qualities and quirks of Nicole (Scarlett Johansson), married to Charlie (Adam Driver), seen through the gaze of what could only be an adoring husband—until the montage is revealed to be a kind of flashback and not a reflection of the present.

The swerve—goodbye, not hello—expresses the shifting of ground beneath their feet that is their breakup, the sense that something unthinkable has happened… except for all the ways in which this eventuality could have been foreseen. Pinpoint-precise in his wit and eye for detail, Baumbach has also made a positively fierce film that, instead of offering swift resolution, dwells on the deep reckoning forced upon Nicole and Charlie by their separation.

Theirs is in many ways a familiar pairing: two artists, an actress and a director, Nicole’s career expanding into big-screen chances after its start in Charlie’s rigorously experimental New York theater company. By the time Nicole heads West, where her family still lives, for a film role, she’s realized and rejected the self-sacrifice that she’s taken for granted in her life with Charlie; he hasn’t accepted as much, and he remains devoted to their union and child with what at first seems a stringently principled stand before it reveals its own desperate depths. None of this is easy—neither the characters’ decoupling nor Baumbach’s feat in steering through this story without making us want to run (kicking and) screaming. And the greatest stroke of genius is that the writer-director—as if viewing separation now in a kind of reverse shot from The Squid and the Whale—realizes fresh psychological and literary potential in the drawn-out process of divorce, lawyers, and the whole damn thing.

Marriage Story (Noah Baumbach, 2019). Courtesy of Netflix.

Marriage Story largely consists of shuttling back and forth, between present and past, between West and East, between lawyers and Charlie/Nicole. It will be rightly praised for Johansson’s breathtaking tightrope walk as Nicole extracts and recenters herself; the star shows a stripped-down, vulnerable candor that hasn’t been apparent for quite some time (and in the sort of role one hopes begins a new chapter in a career). As for Driver, he adds another entry to a riveting and idiosyncratic reconstruction of masculinity that for my money began on TV with Girls and his self-consciously odd portrayal of a dude, which simultaneously incorporated and refracted how said dude was perceived by women. Charlie exhibits all the classic symptoms of blinkered self-absorption as a capital-A artist, leading his troupe (which includes Wallace Shawn) into new frontiers, but his attachment to their child and the idea of home makes it hard to write him off. Part of the film’s poignancy lies in watching Nicole work her way up to giving herself permission to take on the same kind of independence and autonomy he enjoys. It’s a shift aided and abetted by the attorney (Laura Dern) helpfully recommended by someone on the set of the CGI epic Nicole is starring in.

At first, grey comedy emerges as Charlie lawyers up with a bulldog attorney (Ray Liotta at his best in years) whose game plan for a custody battle is to identify the worst interpretations of the opponent’s behavior and the greatest monetary risks. In these scenes and in his encounters with Nicole (while visiting their kid on the West Coast, and her), Charlie clings to an ideal of good faith, best intentions, dammit we aren’t people who need lawyers, etc. Baumbach brilliantly tunes into the legal jockeying—Charlie instead settles on the grandfatherly, lower-key lawyer played by Alan Alda—as a mix of proxy warfare and some warped form of projection. As the counsels each explain to their clients how their side will be perceived, and what will be judged good or bad parenting, and how much equity can be expected to change hands, we watch the worst possible motives being ascribed to Nicole and Charlie, and we also witness them tempted and goaded into greater aggression than is typical of their personalities. It’s all a kind of rewrite of their life stories, their lawyers helping fuel (or pour fuel on) the movie’s emotional narratives rather than playing the usual anonymous suits in one-off consultations. Johansson’s most spectacular moment comes in a long-take scene in conference with Dern, which turns the lawyer’s strategic pep talk into a confessional monologue and a searching rumination. The film’s many intimate close-ups (shot by Robbie Ryan, DP on The Favourite) and some surprising setups suggest Baumbach reaching for an expression of rupture.

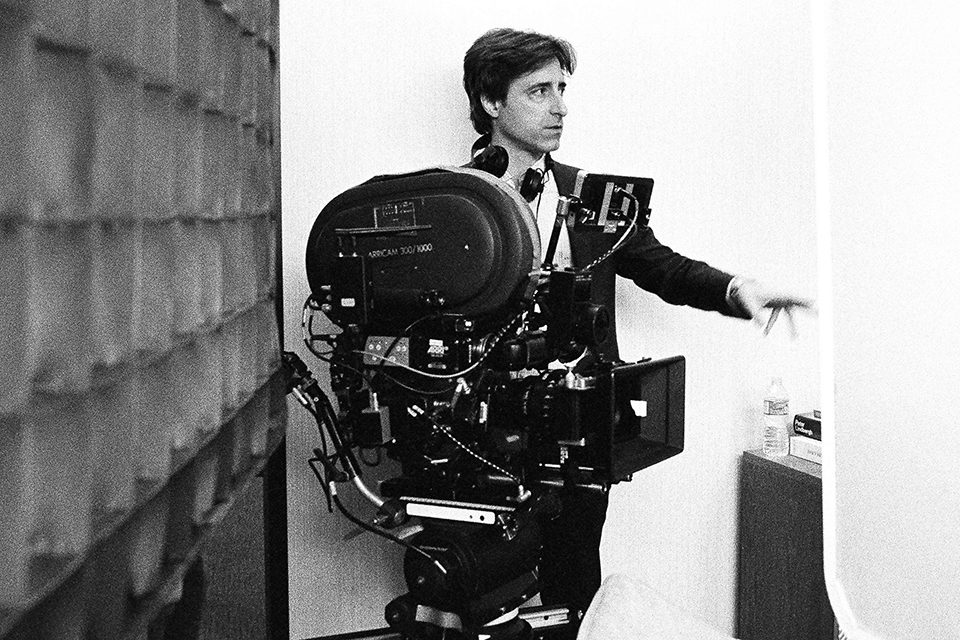

Noah Baumbach. Photo by Wilson Webb/Courtesy of Netflix.

Eventually Nicole and Charlie realize they’ve initiated a kind of mutual assured destruction they’d rather not see through, but not before one more knock-down drag-out nowhere-to-hide argument. The two face each other in the almost stagelike barren apartment that Charlie is renting in L.A. for his visits from New York (feebly he keeps insisting to any who will listen, “But we’re a New York family!”). Buried and not-so-buried resentments and fury rise to the surface, shadowed by (lingering, disappointed) affections and culminating in the kind of invective that could only be flung between those who know each other too well. The scene’s an incredible feat, showing off not only the actors but also another side of Baumbach, a filmmaker who often sticks to the edge of clever social satire (that is albeit saved by the relentless sharpness of his commentary). Baumbach is ever capable of dropping the little detail that can crystallize an entire milieu (like the film’s mention of a play where one could “smell the bacon,” probably a micro-reference to an actual 2009 production of Our Town), but Marriage Story also shows the auteur able to cut himself loose and sit with new ranges of raw feeling.

Will they laugh about it someday? We certainly do, while we’re watching. In case it’s not apparent, Marriage Story is both funny and painful, often at the same time. Its worlds also extend beyond Nicole and Charlie’s dyad, most notably to her dysfunctional family (mom Julie Hagerty still googly-eyed over Charlie, sister Merritt Wever stuck in gear) and the glimpsed close-knit realm of Charlie’s theater gang—and one might also add Martha Kelly’s ineffably strange but dead-on turn as a court evaluator. It’s a movie that should propel Baumbach (not that he needs propelling, in his disciplined and unified oeuvre) in front of more and newer eyes than his past movies have tended to do with their sometimes miniaturist-local bent. These are scenes from almost-after a marriage, from within the great human tragicomedy, as personally felt and indelibly etched as they would feel to those inside the maelstrom.

Closer Look: Marriage Story is the Centerpiece selection at the New York Film Festival and opens in theaters on November 6.

Nicolas Rapold is the editor-in-chief of Film Comment and hosts The Film Comment Podcast.