On a Monday afternoon in the middle of the holiday cluster that the Japanese call Golden Week, the Salonpas Louvre Marunouchi in central Tokyo was mostly empty. Attendance was concentrated at the back of the theater, where three rows had been designated as “Premium Aroma Seats.” There, patrons waited to be wafted back to the 17th century by a special smell-enhanced presentation of Terrence Malick’s The New World.

The history of attempts to combine cinema with smell is limited. The best-known effort was Michael Todd, Jr.’s Smell-O-Vision, a commercial bust on its single outing in 1960, when Todd pumped synchronized smells into specially equipped theaters showing Jack Cardiff’s Scent of Mystery. For his 1981 Odorama release of Polyester, John Waters used the lower-tech approach of handing out scratch-and-sniff cards at the theater entrance and relying on the viewers to follow on-screen cues (“Do not scratch until you receive instructions from the film,” the cards warned).

For The New World, Shochiku, the film’s Japanese distributor, teamed with NTT Communications to introduce that company’s new fragrance-delivery technology to filmgoers. On the floor of the Premium Aroma zone of the Salonpas Louvre (The New World was also shown this way at one other theater, in Osaka) sat several plastic globes about nine inches in diameter. These balls contained aromatic oils to be mixed and released during the film according to a network-server-controlled timetable.

As the lights dimmed and the curtains moved into place, the floor of the theater shook, and for a few seconds I wondered if I weren’t about to be treated to the unheralded revival of another film-enhancement technology, Sensurround. But it was only a minor earthquake, and, unfortunately, the aroma-fied New World proved less than seismic.

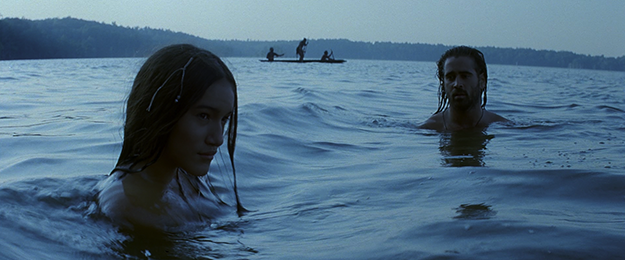

Past smell presentations linked scents to objects visible or implied in the film, like pipe tobacco and baking bread in Scent of Mystery and old socks in Polyester. Scorning such vulgar literalism, Japan Aromacoordinator Association instructor Yukie Nakashima, who mixed the smells for The New World, sought rather to expand on the film’s mood than to play up its realism. This approach had two main consequences. First, the smell track imposed a certain reading—the same one indicated in the printed program, which exhorted the viewer to “enjoy a beautiful love story together with aromatic scents.” The New World was picked as the flagship for Smell-O-Vision 2006 not because Malick’s complex orchestration of image and sound cried out to be raised to the Gesamtkunstwerk level but because the Japanese distributor saw the film as essentially a love story in a pastoral setting and, as such, ideal for aroma enhancement.

Although woodsy smells celebrated the English arrival in America, and citrus pervaded the scene at the English court, in general the (predominantly minty) perfumes targeted romantic scenes between Pocahontas and Captain John Smith, making their relationship the focus of the film. Because the appearances of the Algonquin princess’s second admirer, John Rolfe, were usually odorless (so that a viewer might infer that whereas Colin Farrell sometimes smells like peppermint, Christian Bale has no smell), when, after meeting Smith, Pocahontas rejoined Rolfe and took his arm, the floral scent that was emitted put a perhaps sharper period to the narrative line than Malick intended.

The second effect of the smellifiers’ penchant for the suggestive was that when anything appeared on screen that has an odor in real life, its absence from the smell track became conspicuous. So, one sniffed the air in vain for boiling leather, gunpowder, or the ashes with which Pocahontas covers her face; and when, on taking up residence at the colony, Pocahontas smelled the pages of a book, the smell-sensitized viewer felt acutely the lack of a sympathetic aroma in the theater.

On the whole, the experience was like watching a movie while an aromatherapy clinic was being held in the lobby. Even in my Premium Aroma Seat, I had a hard time distinguishing the scents and often was unsure if a new perfume were being introduced or if a random atmospheric shift had brought a residual scent into stronger focus. Despite the precise synchronization that the NTT technology affords, adding smells to The New World only rendered more diffuse a film that I already found pretty hazy, though I’d seen it twice in the United States (first in the version that was shown briefly in December 2005 and then in the shorter recut that went into general release the next month).

As for the future of the technology, I’d say it’s obviously better suited to the home than to public screenings. If NTT’s computerized aroma balls catch on (they retail for ¥70,000—about $615), there’s no reason why smell tracks couldn’t be created for consumer use and sold or rented along with DVDs. More interesting results would probably be obtained, however, with the films of, say, Jack Smith or Gregory Markopoulos than with a narrative feature, even one as fragmented in its storytelling and as broad in its sensual appeal as The New World.