Two Views of Robert Altman

The crew, as always, does the hard work, hauling a ton or two of gear down from the hills that overlook the winding Kern River about forty-five minutes outside of Bakersfield. California has been in a six-year drought and the heat is awesome. The surrounding hills are burnt-out, brown and yellow. While the real workers crawl over sun-baked rocks and wade through the clear cold water, building platforms, laying tracks, and setting up cameras and sound equipment, the actors, Fred Ward, Huey Lewis, and I, find some shade and get in the mood for some serious fishing. Huey sits on a boulder, blowing some raw country blues on his harmonica while Fred and I exchange some classy reminiscences about long ago adventures in Mexican whorehouses.

A few weeks before, outside a restaurant somewhere in the L.A. suburbs in which we’d been shooting a sequence with Lily Tomlin and Tom Waits, Fred and I had spent an hour or so in the parking lot learning how to cast a line under the tutelage of Huey, the one true fisherman among us. It seems to come more easily than I thought it would, so it is a disappointment to learn that, for reasons I do not fully understand, there are no actual fish in this section of the Kern. A disappointment because actors, after all, like to do things while they’re acting—hold a gun, tap dance, fly a plane, eat a meal, smoke a (now politically incorrect) cigarette, make love to an absurdly pretty woman. And since I am rarely, if ever, asked to do any of the above—well, I’ve smoked in a couple of movies—I thought that fishing, real fishing, would add an interesting dimension to my professional résumé.

Because actors want to be thought of as interesting. Of course they want to be thought of as talented. And funny. And sexy. And intelligent. And a number of other things. But mostly, I believe, interesting. They want those folks out there to think, hey, that guy can not only laugh and cry and say all those words but he can really play the guitar and catch a football and buck a rivet and make an omelet and catch a fish. That guy is really INTERESTING.

So I have to simulate the special thrill of snatching a big fat live one from the river, a creature that’s been carefully attached to my line by a propman with a basketful of slightly comatose fish. (Note to the ASPCA: no fish were actually killed during the making of this picture. Irritated yes, even insulted, but not killed. I believe that, after we were through shooting, the fish were set free in the Kern where, I like to think, newly inspired by their cinematic debut, they swam gratefully away, hoping to be rediscovered further downstream and selected for a role in the sequel to A River Runs Through It.)

We not only have a fish-wrangler working with us. We have a guy whose job description does not appear on most daily call sheets. We refer to him, for want of any accepted official designation, as the corpse-wrangler. He’s crafted an all too real naked dead girl out of epoxy and plastic and who knows what else. Her face is modeled on that of a well-known porno actress. And she’s been placed in the river near where we—the characters in this segment of Robert Altman’s Short Cuts—have made camp and where she will remain for several days, a silent nagging witness to our anglers’ passion. We know we should do something about her, but we don’t have a phone and we didn’t abandon our wives and children and urban anxieties and lug our camp supplies and fishing gear miles into the hills to be distracted by some stranger’s misfortune. After all, what’s the big deal? She’s going to be dead for a long time. And we’ve only got three days to fish.

It’s a creepy situation—like those in the Raymond Carver stories from which Altman and co-writer Frank Barhydt have fashioned their screenplay. It’s also like a lot of Altman films, in which ordinary decent people commit extraordinary mindless acts and where the banal and the gruesome are constantly bumping into each other.

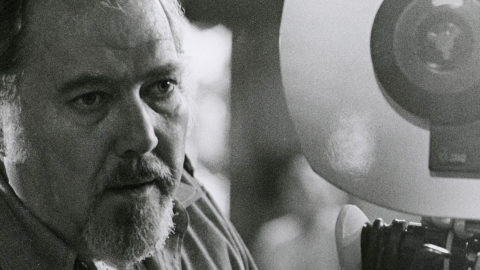

Annie Ross and Robert Altman on the set of Short Cuts (Robert Altman, 1993)

There are a number of reasons actors like to work for Altman. For one thing, it’s fun. ”You figure out who the characters are,” Altman says, “and bring me something interesting.” There it is again. Interesting. There’s not a lot of talk about inner life and motivation. Each one of the actors is in control of a little puzzle inside of them—in this case, a massive puzzle that only Altman has the solution to: twenty-two featured actors are each trying to create a small real life inside the complex pattern of an interlocked and overlapping dozen or so stories going on simultaneously.

Altman generally keeps the camera—in some cases, cameras—out of the actors’ faces. If, as the saying goes, comedy is in the longshots and tragedy is in the closeups, Altman more often opts for a middle distance, content to observe, rather than inspect, the characters’ behavior. It tends to make everyone as important—or unimportant—as everyone else. And it removes the temptation, often succumbed to by many actors who are used to the familiar shooting pattern of master-medium-single, to save their best efforts for the closeups. Altman will frequently shoot a number of takes of a group scene from the same middle distance, each time letting the camera follow a different character. So, in a sense, each actor may be the focus of the master shot when the sequence is edited.

Because all of the actors are miked nearly all of the time, every line, every word, every grunt and groan gets recorded and saved for what must be, for the mixers, a really complicated sound-stew. I am surprised when, after a sequence in which I’m fishing in a particularly noisy part of the river at least a hundred yards from the camera, the script supervisor asks me what the name of the obscure tune is that I was humming under my breath. She makes a note of its title. Everything is of possible use.

And, of course, Altman encourages improvisation—improvised action and improvised dialogue. Improvising dialogue is a tricky business in film, particularly when it’s used in conjunction with written dialogue. The speaking style of the actor is often contradictory to that of the writer’s idea of the way the character is supposed to talk. And the jagged rhythm of improvised dialogue in many films is often neither like that of conversation either in scripted films or in real life. Unlike memorized dialogue, where the emotional arc of the scene is written in and rehearsed and the actor knows when someone else is going to stop talking and it’s his turn, an improvising actor has to make a special effort not to be thinking “what the hell is he talking about?” and “when the hell is he going to stop talking?” and “what the hell am I going to say next?”

It’s a struggle, in other words, to be real and not to be interesting.

Altman tries to keep it simple. The main effort is to keep the dialogue anecdotal rather than programmatic. He suggests a word or a phrase to make the improvisation more fluid in the next take. He tries to get it to sound more like life and less like writing, more like behaving and less like acting. When it works it sounds good and it feels good.

I think it works in Short Cuts. I think it’s real and it’s interesting. But what the hell. I learned how to fish. Sort of.

Robert Altman and Tim Robbins on the set of The Player (Robert Altman, 1992)

TALKING THE TALK

Not having to learn a lot of dialogue is one of the reasons why Altman’s sets are seemingly so anxiety-free. There is a kind of family spirit in which everybody is having a really good time playing an interesting game. And it’s an enormous relief, after a day’s shoot, not to face several hours of memorizing speeches.

I used to wonder why, in the days of silent filmmaking, the actors seemed to have such a prolific social life while they were working. Maybe because they had all those evenings free from the burden of line-learning. If they didn’t get the words quite right, the scripted intertitles would inform the audience of what they were supposed to be saying, thus leaving after-work hours free for glamorous parties, family life, and/or freewheeling depravity.

European films of the ’50s and ’60s, avoiding the problems and expense of recording direct sound and often relying on casts full of actors who spoke in different accents or languages, didn’t seem to care what anyone said as long as their lips moved now and then. Fellini is supposed to have had many of his actors just count from one to ten. The proper words could be dubbed in later, anywhere, and in some cases, by anyone. Sort of like sound effects for the vaguely literate.

The first film I was on that employed a lot of improvisation was Milos Forman’s Taking Off, a film that, in America, everyone liked but no one went to see. In spite of the fact that a number of excellent writers worked on the script, the actors never actually got any pages. Because Forman had been in America a relatively short time and was not yet fluent in the language, he placed a, perhaps, inordinate trust in the actors’ ability to suit the words to the action. What he was really looking for, I think, was dialogue without conscious significance. “Look,” he’d say before a scene—before lots of scenes—”this is—not—important.”

Cassavetes seemed to invite idiosyncratic speech. The more oddball the dialogue got, the more the script supervisor cleared her throat and rolled her eyes, the more Cassavetes nodded happily and smiled his odd, slightly pained, smile.

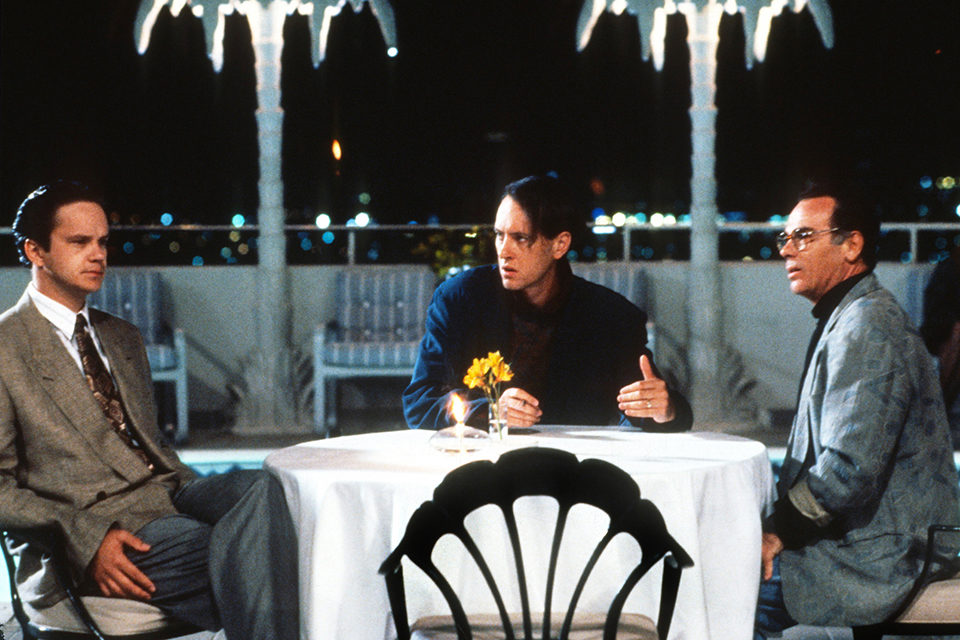

Tim Robbins, Richard E. Grant, Dean Stockwell in The Player (Robert Altman, 1992)

Writers, of course, generally despise improvised dialogue. We all—well, some of us—know the story of Hemingway, who, having received visitors to his walk-up garret in Paris and having been asked where he’d been for the last few days, answered that he’d been right there, lying on his bed, trying to think of the right word. Apocryphal though the anecdote may be, it makes a statement that even the most lonely and neglected screenwriter can relate to, since it is those precious words that are the only proof of our hard work and our superior imaginations (or the superior imagination of our computer’s built-in thesaurus). So we are often bitterly resentful of those who take advantage of our legendarily low position on the filmmaking totem pole–actors and directors who change the words, sometimes change whole scenes, sometimes (arrrgggghhh!) even change the entire endings, of movies. If, however, the changes work, we are perfectly willing to take credit for them.

Most good directors have the ability to lead writers or actors to the place they want them to be in such a way as to allow them to believe that they got there by themselves. Sometimes, in fact, no one can quite remember where the words came from. My brief appearance in The Player is a case in point. Altman asked me if I’d come in and “pitch” a story of my choice to Tim Robbins, playing the head of the studio. So I pitched my purposely lame idea for a sequel to The Graduate. (Although I meant it to be a parody of a concept born of writers’ desperation, several producers and executives asked me, in the first few weeks of the film’s release, if I would like to consider it as a serious project).

The Graduate 2 pitch comes in the now famous opening sequence of The Player, an eight- or nine-minute continuous shot that introduces dozens of characters and accurately portrays the chaotic daily life of a studio, a shot that makes a joke on itself when, toward the end, Fred Ward complains to me—in a more or less scripted dialogue—that they don’t make movies like they used to in the good old days before directors just slapped films together—”cut cut cut.”

In answer, I try to rattle off a bunch of contemporary films that refute his theory, including the example of an extended unbroken shot in The Sheltering Sky in which Bertolucci’s camera follows Debra Winger for a long time. Actually, I didn’t, and don’t, remember the sequence I referred to. It—along with a few other examples—was written on a piece of paper with the lines, a piece of paper that I threw away after the shoot. When The Player opened, a couple of reporters who were writing articles about the film asked me what shot in The Sheltering Sky I was referring to. I told them I didn’t know—that the remark had been scripted. Michael Tolkin, the author of the screenplay, said he had nothing to do with it. Altman said that he didn’t know either—I must have made it up. But I didn’t. Maybe I forgot that Bertolucci called me up and asked me to drop his name, but I doubt it. Who knows where the words, the sentences, and the ideas come from. They appear to actors, writers, and directors in inexplicable ways. Some people call it “God’s gift.” Now that’s interesting.

Buck Henry is an actor, screenwriter, and director, who has contributed his multitalents to such films as The Graduate, Catch-22, The Man Who Fell to Earth, Heaven Can Wait, and Aria.