Up Above and Down Below

For awards-season prognosticators, it all came down to 15 titles this year. The nearest thing to a frontrunner was the plainly filmed but undeniably engrossing Spotlight, but it was hardly on the order of Slumdog Millionaire, Gravity, or even The Imitation Game. The buzzing seemed muted this year, not that I was listening very hard.

In my capacity as a member of the New York Film Festival selection committee I’d already seen most of the other contenders (as well as many others in TIFF’s 289-feature selection, good, bad, and indifferent). The main exception was the hotly anticipated The Danish Girl, Tom Hooper’s follow-up to The King’s Speech. Based, like seemingly every important movie these days, on a “true” story, albeit by way of David Ebershoff’s 2000 novel, it’s about a painter (Eddie Redmayne) in Twenties Copenhagen who discovers a predilection for transvestitism after posing in drag to help his wife (Alicia Vikander) complete a portrait of a woman. He continues to model en femme for further paintings, and while his wife’s art career takes off, he comes to realize that transvestitism is a mere way station on the road to a sex change. Predictably enough, this provides Redmayne with a perfect showcase to follow up his performance in The Theory of Everything with another transformative albeit very different star turn. Maybe lightning will strike twice for director and actor, but while the material has a certain intrinsic interest, the film is overly solemn and tasteful, and doesn’t quite ignite as a crowd-pleaser.

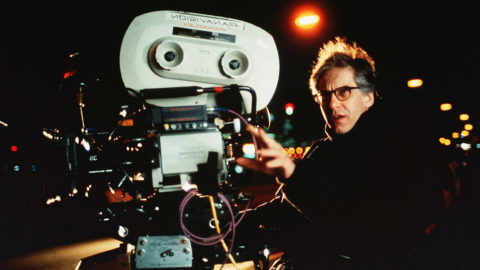

High-Rise

TIFF always manages to land a few must-see world premieres and this year was no exception. Expectations were high for two films from the U.K. that couldn’t be less alike. I wanted to love Ben Wheatley’s ambitious J.G. Ballard adaptation High-Rise, an impressive, visually ingenious wallow in decadence, but it ultimately succumbed to entropy, in large part because it failed to solve the classic problem of adapting a novel whose main character is passive. For an hour, Tom Hiddleston’s protagonist, a doctor, nonchalantly learns the ropes of life in a brand-new luxury tower block and observes the simmering tensions between its stratified inhabitants—so far so good. But as the building’s unstable social structure disintegrates into anarchy and murderous class warfare, the only way Wheatley and his perennial writing partner Amy Jump could maintain audience interest is by making their main character finally do something, all the more so given how claustrophobic the action becomes. Unfortunately they chose not to. Cleverly set in the mid-Seventies at the time of the novel’s writing, High-Rise is an honorable, fascinating mess and I look forward to seeing it again. (It has yet to find a U.S. distributor.)

And then there was Terence Davies’s even more anticipated Sunset Song, adapted from a 1932 novel by Lewis Grassic Gibbon. Set on a farm in northern Scotland on the cusp of World War I, it features an exceptionally strong central performance by Agyness Deyn as Chris, the bright daughter of a brutish farmer (Peter Mullan in top form) who sees her educational prospects and consequent hopes of a teaching career evaporate following the suicide of her mother and the departure of her brother. With great exactitude, Davies traces how Chris’s bleak future as her father’s housekeeper is averted and where life takes her, imbuing the action with an unostentatious tenderness and eliciting uniformly lovely performances from the rest of his cast. As a study in hardship, brutalizing family life, and romantic loss, Sunset Song is a deeply felt return to territory with which the director is intimately familiar. At first I wasn’t sure about the bold and unexpected shift in point of view in the film’s final stages, but the effect is absolutely devastating, and on reflection it’s a perfect move. Nothing short of sublime, Sunset Song ranks with The House of Mirth and The Long Day Closes among Davies’s finest achievements.

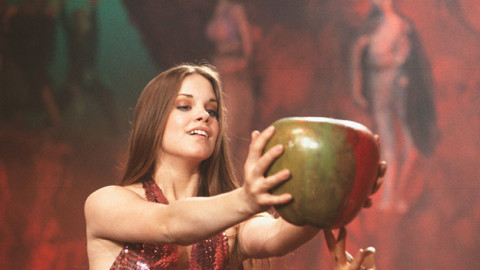

Hardcore

And from the sublime to the ridiculous: in an impulsive last-minute schedule decision that speaks volumes about my debased film-viewing priorities, literally three minutes after Sunset Song had come to an end, I was strapping in to watch the ultraviolent Russian cyborg romp Hardcore, the talk of the town since its Midnight Madness screening the previous night, which saw viewers in the front rows of the Ryerson Theatre running for the bathrooms stricken with motion sickness. So, clearly a must-see. The film’s gimmick is that the nonstop and waaaay over-the-top action is filmed entirely from the POV of a resurrected half-man, half-machine super-soldier—a mute Six Billion Ruble Man I suppose. By the time Hardcore gets around to filling you in on what’s at stake (if anything), it’s obvious that director Ilya Naishuller couldn’t care less, and you probably won’t either. Enlivened by the manic presence of Sharlto Copley in at least a dozen different roles, this is nevertheless a film that sooner or later wears out its welcome for all but the most degenerate videogame-movie aficionados. With an unprecedented but monotonous body count, Hardcore accomplishes its unstated mission to create the cinematic equivalent of a first-person shooter. The title is less a description of its contents than a definition of its target audience. I have seen the future of cinema and it made my eyes and ears bleed.

Midnight madness reliably yielded other treats for the bloodthirsty, of whom there seems to be no shortage in Toronto. Adopting a neat road-movie framework, Southbound did the horror-anthology tradition proud, with no weak links among its five deftly interconnected tales of terror, ably directed by Roxanne Benjamin, David Bruckner, Patrick Horvath, and four guys who go by the name of Radio Silence. And although I seem to be in a minority of one, Nick Simon’s truly nasty The Girl in the Photographs did it for me. In an authentically repellent scenario, a young woman (well played by Claudia Lee) is stalked by a serial-killer duo who present her with photographs of their victims. When the story and the pictures go viral, it attracts the attention of a hateful West Coast celebrity photographer (Kal Penn) in search of a new aesthetic. It’s nihilistic stuff to be sure, but it’s also an original, creepy variation on the otherwise extremely tired format of the so-called slasher film (always the laziest of labels considering Halloween is widely considered to be its progenitor). And straight out of Turkey, Baskin, which roughly translates as “police raid,” was perhaps the biggest surprise of the section, and the least straightforward in its approach to genre. Following five cops who enter a derelict building in a remote village, discover a charnel house, and then descend into a nightmarish netherworld, Can Evrenol’s film delivers the requisite genre satisfactions. But things are clearly not what they seem—from the get-go the action is periodically arrested by intriguing slippages that appear to reset the narrative, perhaps suggesting a dream that never ends—or something like that. One thing is certain, however, and that’s that Evrenol is a talent to watch.

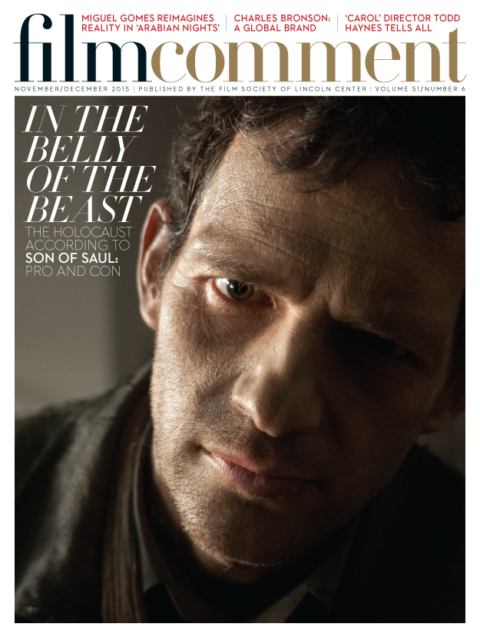

Demon

So is Evrenol’s countryman, writer-director Emin Alper, whose cryptic, brooding Frenzy also deploys a strategy of narrative slippage and pervasive ambiguity and dread in its story of a man released from prison on condition that he report on any subversive activities he detects in his Istanbul neighborhood—activities that may or may not involve his troubled younger brother. As Frenzy unfolds, its depiction of a country rife with intrigue, paranoia, and social unrest becomes ever more unmoored, with the film’s events increasingly appearing to be taking place in the minds of the two main characters, the point of view shifting back and forth between them. The film is a puzzler, but it’s gripping and is further evidence that something exciting is going on in Turkish cinema.

The final word should rightly go to the remarkable Polish-Israeli co-production Demon, whose director, Marcin Wrona, died suddenly at age 42 shortly after the film premiered in Toronto. Like Frenzy, Wrona’s third narrative feature inhabits a realm of disquiet, but in this case that disquiet originates in history and its burden. Fittingly, the film opens with a digger being driven through a country town—this is a film about unearthing a past that haunts the present. This haunting comes in the form of a dybbuk, which according to Jewish folklore is the soul of someone who has not received a proper burial. The story begins with young English engineer Peter (Itay Tiran) moving into an abandoned country house owned by his bride-to-be’s family. While excavating the house’s grounds on the eve of the nuptials (why I don’t know), he uncovers human remains, but reburies them and says nothing—even when things go bump in the night. The next day however, during the course of the couple’s traditional Polish wedding and its celebrations, Peter begins to unravel until he is violently possessed by the spirit of a young Jewish woman. But make no mistake, despite its unambiguously supernatural premise and its deeply unsettling effect, Demon’s intentions have little in common with the horror genre. Rather it is a tough-minded take on the chickens coming home to roost. Tiran, an Israeli actor, anchors the film with a mesmerizing, literally convulsive performance, but Wrona’s direction is something to behold: he demonstrates complete control of his material and a real visual flair—his dynamic staging and sinuous camerawork are the stuff of high-level filmmaking. Cinema has lost a unique talent who, with what is now his final film, was poised to enter the major leagues.