Thinking Inside the Lightbox

After 10 years of covering the Toronto International Film Festival and in view of the festival’s inauguration of its Bell Lightbox facility, now might be a good time to take stock of things. TIFF is an essential festival—for North America’s press and programmers, and, above all, for the people of Toronto. In terms of sheer scale, it’s the movie equivalent of one-stop shopping.

But like the city, the festival suffers from an overall characterlessness. It’s pleasant enough, well-run, but impersonal, and somehow generic. A couple of its more peripheral niche sections—Midnight Madness (genre movies from horror to martial arts, presented with plenty of showmanship) and Wavelengths (experimental film, meticulously presented with care and respect)—have carved out strong identities and audience followings for themselves. In both cases that’s partly because they’re neighborhood- and venue-specific and partly because they’re identified with programmers who put a human face on things.

Otherwise, the puzzling blandness of the festival as a whole is epitomized by the names of its main sections: Gala Presentations (20 high and not-so-high profile prestige pictures and soon-to-be-released Hollywood titles); Masters (“the world’s greatest filmmakers”—among this year’s select group of 13 were Amos Gitai and Jørgen Leth); Discovery (filmmakers unknown to most of us—seriously, I’d only heard of one out of 27); Vanguard (11 edgy films by more or less known filmmakers); Visions (work by 11 filmmakers none of whom are visionary by any stretch of the imagination, except maybe Michelangelo Frammartino—and Vincent Gallo, of course); Real to Reel (documentaries—geddit?); Canada First! (a sad little six-feature and 40-shorts ghetto of local efforts, named with uncharacteristic TIFF irony, since it’s on page 371 of the 448-page festival catalogue); and then there’s the snappiest section name of all—Contemporary World Cinema (of its 51-film miscellany, 13 were by major talents who deserved to be parked anywhere but here).

Confessions

It’s surely symptomatic that the catch-all Special Presentation category is now the largest section of all, containing a ridiculous 59 films this year, all of them “special,” and maybe half of them made by artists like Clint Eastwood, Benoît Jacquot, and Mike Leigh who evidently still haven’t achieved the mastery of a Gitai or a Leth—keep trying, guys! In short, though you can see many of what will come to be regarded as the best films of the year here, there’s little rhyme or reason to the programming. Were it any more inclusive, I’m not sure it could even be described as programming at all. But to mention just one letter of the alphabet, the festival passed on Kiarostami, Kitano, Kechiche, and Keiller, so it’s unfair to suggest that taste isn’t being exercised. But there sure are some weird calls: Rachid Bouchareb’s Outside the Law belongs here but Cristi Puiu’s Aurora doesn’t? Really? Seriously?

How is it that a festival seemingly this lacking in vision and blessed with such mystifying judgment has become so indispensable? In the end, it may simply be an accident of geography. Toronto is so damn easy to get to if you’re American, compared to Cannes, Berlin, or Venice. The people at the top of the festival’s 19-strong curatorial team are world-class programmers, and as with most big-money festivals, they’re surely straitjacketed by the interests and agendas of their corporate and civic sponsors—now more than ever. (The festival may be slightly less a prisoner of its agenda of multicultural inclusivity than before, given that the disappearance of its Planet Africa section went unnoticed.) And with the launch of the indisputably impressive Lightbox, the stakes are a hell of a lot higher now.

Perhaps the greatest edifice dedicated to film exhibition in North America if not the world, this elegant, five-screen state-of-the-art facility is Canada’s airy, inviting answer to Cannes’s dark and daunting Palais bunker, an architectural monstrosity if ever there was one. The Lightbox’s opening was very Canadian—low-key and tasteful, without a trace of grandiosity. This was TIFF’s quantum leap that wasn’t. Next year will be when the game really changes, I assume.

Deep in the Woods

If you compare TIFF’s programming with that of the Venice Film Festival, which I attended just once to serve on a jury, the contrast is striking. As Olaf Möller’s report on page 54 indicates, many of the same films playing in Toronto show up in Venice first. Whether in the main competition (24 films), out of competition (24 films), or its more envelope-pushing Horizons competitive section (21 features), Venice’s placement of films is often marked by mercurial risk-taking and strategic calculation that inevitably invite speculation and interpretation from its audiences and the press corps. This is programming that inspires engagement. At the same time, Venice isn’t saddled with the mandate of being a something-for-everyone movie Wal-Mart. Nor is it a clearinghouse for films from Cannes, Berlin, Sundance, and points beyond, a mission holdover from Toronto’s former identity as “the Festival of Festivals.” If only TIFF could be as adventurous and unpredictable and imaginative as Venice strives to be, for better or worse.

What about the films then? Lots of good ones, a few great ones, nothing so flat-out terrible that you walked out or even thought about it.

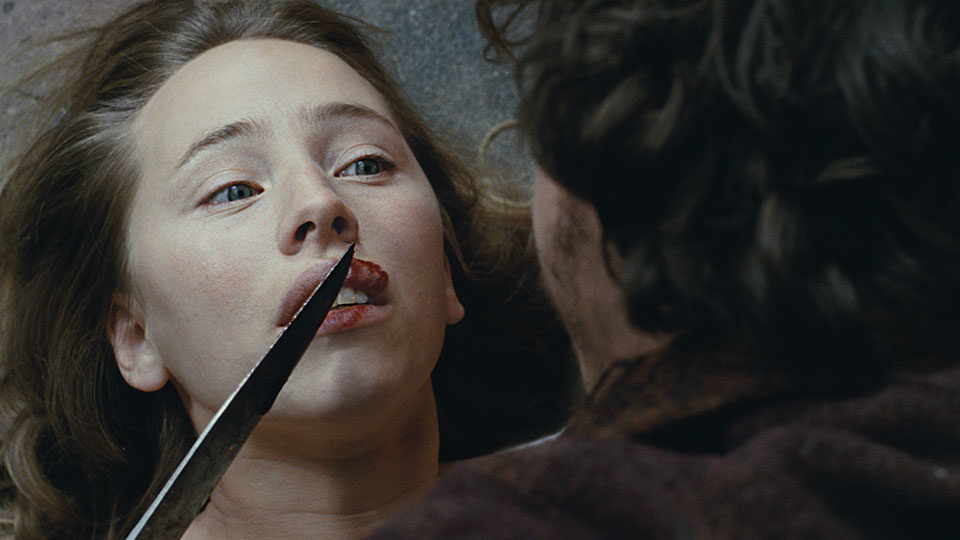

The standout for me was Benoît Jacquot’s singularly engrossing but widely dismissed Deep in the Woods, in which the director’s perennial muse Isild Le Besco plays an upper-middle-class girl in a village in 1865 Provence who literally falls under the spell of a young vagabond (Nahuel Pérez Biscayart) with uncanny mesmeric powers. Still in his thrall after he rapes her, she joins him on his cross-country wanderings, as an irrational and obsessive psychosexual dynamic plays out between them. Based on a real-life case, and filmed with an exquisite feeling for the Provençal landscape, it’s a fascinating and fully-realized study in amour at its most fou—and Jacquot’s best film to date.

Neds

The vicissitudes of youth got a workout in several memorable films. The unexpectedly compelling Neds, Peter Mullan’s tough, unsentimental follow-up to The Magdalene Sisters, chronicles the coming-of-age of a highly intelligent but volatile teen with oedipal issues who falls in with a neighborhood gang in 1972 Glasgow, and features a powerful debut performance by Conor McCarron as the troubled protagonist. In the surrealism-tinged Curling Denis Côté depicts an idiosyncratic, barely verbal, but tender relationship between a loner father and his daughter. Set in snowbound rural Quebec, it’s full of casually enigmatic incident and remains firmly entrenched in its characters’ disturbing eccentricities and involuted community. And Tetsuya Nakashima’s extraordinary Confessions, a box-office hit in Japan, recounts the revenge of a high school teacher on the students responsible for her young daughter’s death, through a series of interlocking voiceover monologues from multiple points of view. Sustaining a fugue-like, intensifying counterpoint of sound and image over 103 minutes, it’s truly mesmerizing, and in terms of structure and articulation, hands down one of the most original films I’ve seen recently, affording a glimpse of another possible direction 21st-century cinema might take.

Midnight Madness’s big coup was the premiere of John Carpenter’s first film in almost a decade, The Ward. In it, the specter of a deceased patient preys upon the inmates of a psych ward for troubled teenage girls. If it wasn’t a return to form on the order of The Thing or They Live, it sure was an improvement on Ghosts of Mars and Vampires. Carpenter still knows how to creep you out, there’s a strong lead performance by Amber Heard, and the film has some nice twists—and it gives the “final girl” convention a new spin.

Shades of Roger Donaldson’s The Quiet Earth and David Twohy’s Pitch Black, Brad Anderson’s effectively creepy Vanishing on 7th Street made the most of its Twilight Zone–ish premise—the entire population of the world instantaneously disappears following a global blackout, leaving only a few baffled and increasingly strung-out survivors. Whether you’ll root for them to stay alive as the devouring darkness encroaches, however, may depend on how you feel about Hayden Christensen, Thandie Newton, and John Leguizamo.

Curling

The vampires in Stake Land aren’t boyfriend material—they’re leprous, black-goo-oozing, feral beasts. A postapocalyptic road movie with a touch of the Western and featuring Kelly McGillis as a conflicted nun, Jim Mickle’s film proves there’s still life in the vampire subgenre. Along the lines of I Am Legend, it depicts a world decimated by a vampire virus, with what’s left of humanity either barricaded in rural enclaves or roaming the land with the Brethren, a Christian fundamentalist militia. Through this Road Warrior landscape a boy and his vampire-slayer mentor drive East in search of a rumored sanctuary. Mickle delivers the requisite scares and gruesome mayhem with a refreshingly down-and-dirty, gritty approach.

Last—and by universal fan-boy acclaim—best was James Wan’s super-scary reinvention of the haunted-house genre, Insidious. Patrick Wilson and Rose Byrne play a couple who move into a new house; soon enough things go bump in the night, apparitions appear, and their son falls into a mysterious coma. Finally the family decamps—but it’s only once they move into their new home that things get really frightening. Enter a medium, paranormal investigators, a mother-in-law played by Barbara Hershey . . . and then there’s a twist that—enough said. In his endearingly logorrheic intro, an irrepressible Wan, director of the original Saw, revealed that one of the rules he and writer Leigh Whannell set for themselves was that there would be no false scares. They never break that rule, and if that’s music to your ears, this is a must-see.