Every year, the Toronto International Film Festival seems to get a little bigger. And every year, those who attend seem compelled to comment on this. This year, with a program boasting 288 features (almost 150 of them world premieres) and 78 shorts from close to 70 countries, the organizers chose to tackle the issue head-on and pre-emptively. “Are we too big?” asked Cameron Bailey, TIFF’s artistic director, in his welcome letter in the official catalog. “No, because big works in Toronto,” was his answer.

With its legion of 2,500 orange-clad volunteers, TIFF certainly handles “big” with admirable order, efficiency, and ease. But “big” in TIFF’s case is also more than a variable to be managed. It has in many ways, especially in the absence of a distinctive curatorial line, come to be the Festival’s defining characteristic, its identity. It is certainly what has fostered TIFF’s emergence as a focal point in the global film ecosystem. Toronto matters because it is big. And if for viewers that means feeling at times overwhelmed, to use Bailey’s words again, in a “limitless swirl of cinema” and crowds . . . well, there are certainly worse ways to feel. Especially at a time when film and the theatrical experience are, if not quite yet threatened, certainly in crisis.

12 Years a Slave

Amid the swirl, you forge your own small path. It is incomplete of course, and subjective, necessarily. Yet out of the chaos of abundance, the differing tastes, and the ever-raging war between intellectual elitism and unbridled viewing pleasure, the sheer power of certain works still manages to command consensus. This year’s audience award winner, Steve McQueen’s piercing 12 Years a Slave immediately comes to mind—it’s a portrait of American slavery that’s neither sentimental nor sensational (kind of an anti-Django Unchained). Other such titles include Alfonso Cuarón’s visual tour de force Gravity, and Incendies director Denis Villeneuve’s first big American film, the unhurried morally charged thriller Prisoners. Powerful and star-studded, these were released soon after the festival ended—Toronto is also, let us not forget, one of the favored launching pads of the awards season.

Tom at the Farm

Farther from the relentless spotlight of the red carpet, Tom at the Farm by Canadian wunderkind Xavier Dolan was certainly a highlight and a confirmation of the undeniable talent of this rising voice of Quebec cinema. If his first three films (I Killed My Mother, Heartbeats, Laurence Anyways) could be grouped as a loose trilogy on impossible desire, the 24-year-old director appears, at first, to be moving in a very different direction—straight into genre territory—with his latest. Based on a play by Michel Marc Bouchard, the story concerns a young advertising copywriter, Tom (played by Dolan), who travels to the countryside to attend his lover’s funeral. The deceased’s quietly grieving mother—mothers are always central to Dolan’s imagination—remains unaware that her son was gay, and in dire need of sympathy, she is quick to welcome Tom. The other son’s reception is a little more hostile. Slowly, and not entirely unwillingly, Tom gets drawn into their insular web of madness. Needless to say it is not the Transcendentalist spirit of Thoreau that hovers over this grim little rural patch, but that of Patricia Highsmith and certainly Hitchcock, to whom Dolan enjoys making reference throughout, from the early shower scene to the cornfield chases that evoke North by Northwest. The strictures of genre prove bracing to Dolan’s ravenous filmic enthusiasm, tightening his direction, reining in the excesses he allowed himself in his early works, and sharpening his provocative inventiveness. But what makes Tom at the Farm a particularly interesting work is that under the guise—the very efficient guise—of a psychological thriller lies another more intimate, poignant piece on love and mourning. It is this unusual mix of spine-tingling and heart-wrenching that leaves such an enduring mark.

The Unknown Known

There are of course many ways to disturb. A vortex of love, violence, and madness is but one. Probing the mind of Donald Rumsfeld—as Errol Morris does in The Unknown Known—is another. Rather than conducting a classical interview, as he did with Robert McNamara in The Fog of War, Morris has Rumsfeld read and explain some of his “snowflakes,” the tens of thousands of memos he wrote in 50 years of political life (20,000 during the Bush administration alone). It’s a bold and radical line of inquiry given the notorious subject matter. Morris does not cross-examine or contradict his subject. He does not try to extort a confession. He just lets us into Rumsfeld’s mind. It’s a riveting and quirky ride, it must be said (even during his time in office, and in the darkest of days, Rumsfeld’s press conferences were unusually entertaining), were it not for those all-too-real consequences in recent history… The result can at first feel less satisfying than The Fog of War. Morris likes to quote his wife who likens McNamara to the Flying Dutchman, “traveling the world looking for redemption that he’ll never find” and Rumsfeld to the Cheshire cat—“all that’s left at the end is a smile.” Rumsfeld does remain impishly unapologetic—and not wholly unlikeable—throughout. The closest he comes to regret is admitting that “certain things shouldn’t have happened” when faced with the Abu Ghraib scandal. There is no sense of contrition, no reassurance of humanity, no prospect of understanding. And you cannot even bring yourself to detest the man. For a while you are left wanting, until you realize that this feeling of unquenched uncertainty may well be the deeper human truth.

Quai d’Orsay

Rumsfeld would have felt at home in Quai d’Orsay, Bertrand Tavernier’s In the Loop–style take on French politics and international diplomacy. In fact, he would have been a better casting choice. Based on a graphic novel, itself more than a little inspired by the dashing Dominique de Villepin, France’s charismatic foreign minister at the time of the Iraq War, Quai d’Orsay is an uneven film. The script is wickedly smart, strewn with gems, but poorly served by a miscast, overly goofy Thierry Lhermitte as the lead (the supporting roles on the other hand are pitch-perfect, especially Niels Arestrup as the chief of staff). As a result, the tone oscillates uncomfortably between brainy satire and heavy farce, weakening the film’s sharpness of insight.

Night Moves

The intensity and profusion of a festival schedule instills a not entirely unpleasant feeling of captivity that encourages surrender. It also privileges immediacy. You are rendered more vulnerable to the work while at the same time having less time to reflect upon it. A few titles will immediately stand out. But others, at first dismissed, might slowly come back to haunt you. This happened to me with Kelly Reichardt’s Night Moves, in which a trio of young eco-warriors (Jesse Eisenberg, Dakota Fanning, and Peter Sarsgaard) come together to bomb a dam in order to shake up public consciousness. They then go their separate ways only to confront a growing sense of futility and paranoia. From the slow, meticulously filmed preparation of the act to the tensely dilated period of doubt (the film’s second and stronger half), an odd languid thriller emerges.

Starred Up

If Reichardt keeps things on a low flame, David Mackenzie does the very opposite in the brutally authentic British prison drama Starred Up (the title is prison slang for when a young offender is transferred from a juvenile to an adult facility). Shot sequentially and on location in a Victorian prison in Belfast, with a shaky but minutely calibrated camera style, in at times barely intelligible British prison slang (which actually bolsters the primal impact of the film), Starred Up is no mere depiction but a jolting immersion in the claustrophobic mix of violence and vulnerability that is prison life, and it’s powered by Jack O’Connell’s riveting performance as violent criminal Eric Love. It is also, in this unlikeliest of settings, an intensely charged father-and-son story.

Club Sandwich

Mexican director Fernando Eimbcke’s delightful Club Sandwich focuses instead on a mother and her son, who’s on the cusp of manhood. Their fusional and delicately ambiguous relationship comes under threat during a bargain off-season trip to an empty, sunny resort. The film is a very small piece, as narrowly focused as the endangered bond it depicts, but it’s a hilarious and poignant one, so terribly well observed and restrained that it manages to leave you both melancholic and quietly jubilant.

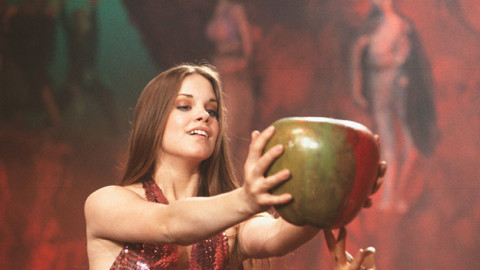

Under the Skin

Saving the best for last, Under the Skin, Jonathan Glazer’s very personal and pared-down adaptation of Michael Faber’s novel, was perhaps TIFF’s most striking film. It reinvents Scarlett Johansson as a mysterious, voluptuous alien being who drives through the Scottish landscape (hypnotically filmed as a palette of grays), picking up men along the way. With images and a soundtrack (by Mica Levi) of staggering strangeness and beauty, and very few words, Glazer delivers a great film about otherness and solitude. Johansson is mesmerizing as the extraterrestrial heroine: robotic and predatory at first, then increasingly curious, as she slowly—and mostly silently—deviates from her mission. It is a dark, sensual, and interior work that runs counter to the standard space-alien genre, which is probably what makes it such a captivatingly otherworldly object.