Stranded

Programming a documentary film festival can’t be an easy task: wading through hour after hour of war, death, disease, environmental crises, and personal tragedies, in films too often artlessly made by anyone with access to a camera, computer, and a few dollars. Yearly retrospective selections are also challenging, as there are only so many Fredrick Wisemans, Werner Herzogs, and Errol Morrises out there. All things considered, the Thessaloniki Documentary Festival – Images of the 21st Century, little sister to the city’s larger, better-attended international fest held each November, does an honorable job, offering a number of highlights.

There were some clunkers, too, of course—namely, the agonizing Behave, about Brazil’s juvenile-delinquent penal system, and The Cocaine Jungle, a clumsy, amateurish examination of Colombia’s role in the cocaine industry—but what festival doesn’t have its share of those? And although the 10th edition, which ran March 7-16, featured over 150 films, it’s a pleasantly manageable affair. Daily viewings didn’t kick off until the afternoon hours, sparing attendees the early-morning rush to the theater, and providing them ample time to enjoy the gorgeous Greek city, or to participate in bus tours organized by the festival’s friendly staff. Later in the day, slightly warmer-than-average temperatures greeted exiting moviegoers, helping to alleviate to the grim moods induced by the bleak subject matter of many of the films.

Of these downbeat selections the strongest was Stranded, which tastefully tackles the predicament of the surviving passengers of 1972 Uruguayan plane crash in the Andes (dramatized in 1993’s Alive) that’s only slightly less infamous for its inspirational story of 72 days of endurance than for its reports of cannibalism. For the first time, the survivors, former members of a rugby team, discuss in vivid detail the horrors they experienced and the impact it’s had on their lives since. Their accounts are articulate, sad, and extremely moving, particularly when told from the crash scene they revisit 35 years later. In his impeccably crafted first film, director Gonzalo Arijon mixes in scenes of dialogue-free reenactment so effective that they begin to pass as real.

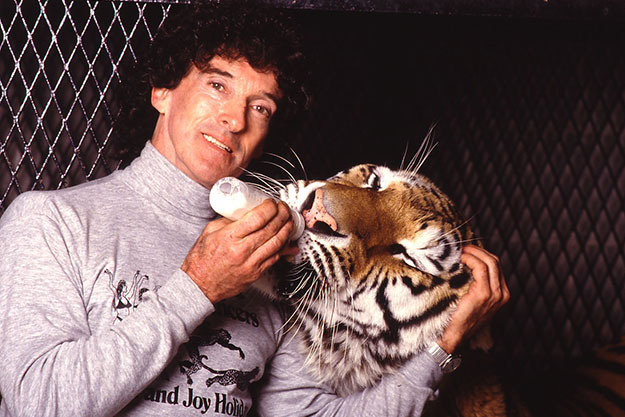

Cat Dancers

The healing of intensely personal scars is also prominent in Cat Dancers, Harris Fishman’s strangely captivating portrait of an American husband-and-wife duo, Ron and Joy Holiday, whose Siegfried & Roy–like onstage routine involved acrobatics with large exotic felines, and their relationship with a much-younger male assistant who joins their act—and eventually their bed as well. With a story like this, the question isn’t, will it end badly, but how badly? Functioning as the engaging, slightly freakish narrator, Ron, downtrodden but still the showman at nearly 70, provides the answer.

Another example of man’s clash with nature is explored in Saving Luna, which chronicles a lonely, playful orca’s persistent efforts to befriend the locals of Vancouver’s Nootka Sound. While many embrace him with open arms, others find him a nuisance and threaten to deal with him on their own terms. To complicate matters further, environmental groups step in to take on the almost impossible task of enforcing an unwritten law forbidding any interaction with the whale. Inevitably, the situation spirals out of hand, eventually becoming the object of media frenzy. Canadian husband and wife filmmaking team Suzanne Chisholm and Michael Parfit, who begin as impartial bystanders and end up falling hard for Luna, capture every step, in comprehensive detail, all the way to the heartrending finale.

Pola Rapaport’s Hair, Let the Sunshine In was a welcome ray of retro light amidst the darkness. The one-hour film considers both the history of the 1967 musical, through lively interviews with former cast members nostalgic for the past—and its future, as a new breed of performers audition for a chance to perform the songs that defined an era. The undying enthusiasm for the show (and the quality of the film) can be indicated by the audience: while showing at 1:30am as the second of a musical-themed double bill (a late start even by Greek standards), not a single person left the packed theater and a few engaged in a sing-along.

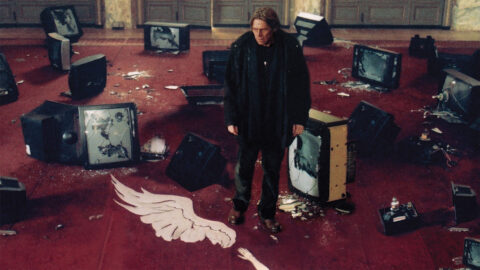

Pavlov’s Dogs

One of this year’s tributes was to Finnish documentarian Arto Halonen. Not exactly a household name, Halonen has a filmography well worth checking out, even if just for Pavlov’s Dogs (05), his fascinating look at Russian psychologist/entertainer, Sergei Knyatzey, who, inspired by behavior modification tests performed on dogs by scientist Ivan Pavlov (Knyatzey prefers pigs and cockroaches), makes his living providing the wealthy with new experiences, including a role-playing game that gives them a taste of poverty by pretending to be homeless. Halonen’s other films, eight were shown in total, cover a wide range of cultural ground, including Cuba’s troubled society, the Temiar Senoi tribespeople of Malaysia, film projectionists in Kyrgyzstan, and government propaganda in Turkmenistan.

Also honored were the acclaimed American doc duo Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, with screenings of all of their features, as well as their episodes of Iconoclasts from the Sundance Channel.

With so many festivals popping up around the world—many of them with a nonfiction focus—it’s difficult to distinguish one from the next, but Thessaloniki seems on its way to becoming a major European festival destination. Despite an arguably too heavy emphasis on Greek cinema, it has the location and the programming to more than warrant the recognition.