The Strength of Street Knowledge

The pioneering filmmaker John Singleton, who died of a stroke earlier this year, at 51, left behind nine films, virtually all of them laced with powerful social commentary and a cinematic style that echoed the humanist tradition of François Truffaut and Vittorio De Sica. The news of his death was a reminder of how things have changed in Hollywood, where he helped pave the way for a new era in black filmmaking. It’s no exaggeration to say that without John Singleton, there would be no Barry Jenkins or Ryan Coogler.

Boyz N the Hood, which Singleton both wrote and directed, set new standards for realism in stories about everyday black life. Inspired by his own experience, it showed the devastating effects that dead-end poverty, gang violence, and absentee fathers have on families in South Central Los Angeles. When the film opened in July 1991, following a 20-minute standing ovation at Cannes, it caused such a sensation that Singleton’s story became the stuff of legend. Here was a nerdy-cool filmmaker of color—barely into his twenties, USC-trained, South Central-bred—who took Hollywood by storm. His $5.7 million movie went on to gross $100 million and score a pair of Oscar nominations for Singleton, including best director, the first for an African-American. Steven Spielberg later said that the film’s gut-wrenching sequence of Tre’s body being brought home to his devastated mother was one of the most powerful he had ever seen in movies.

When I first met Singleton more than 25 years ago, after my brother Anthony—who photographed him for a New York Times Magazine cover story—introduced us, he had a swaggering confidence, keen mind, unflagging energy and ironic sense of humor, not unlike his movies. He was in New York for the Malcolm X premiere, and when we ran into each other again at the glitzy after-party, I remember circling the room as we chatted excitedly about Spike Lee’s impassioned bio-epic, starring Denzel Washington. Like every other black film buff at the time, we both worshipped Lee, whom Singleton credited for his career. Over the years we managed to stay close, sometimes meeting up for dinner or a movie. We talked about our kids (he was a dedicated father of seven), and all sorts of stuff (he was encyclopedically well-informed). Occasionally, he’d run scenes by me or ask me to read a script-in-progress. I considered him a friend, as well as a regular interview subject and mentor. One of the first stories I did was on Magic Johnson’s newly launched chain of multiplexes, in which Singleton stressed the need for quality amenities in theaters that catered to underserved neighborhoods, so they, too, could experience movies as the filmmakers intended.

The start of Singleton’s career coincided with the black film renaissance that emerged in the 1990s, when directors like Spike Lee, Reginald Hudlin, and Mario Van Peebles suddenly found the studio gates wide open to them, thanks to the disproportionate number of tickets purchased by African-Americans and various cultural trends. Until then, Hollywood had rarely told black stories—and if they did, the films were almost always directed by whites, which placed a measure of distance between the material and the moviegoer. Singleton and others obliterated that model by making movies from an Afrocentric (and mostly male) perspective.

Singleton’s early works, still his strongest, brought a groundbreaking hybrid of contemporary subject matter and racial politics. In movies like Poetic Justice and Higher Learning, he showed a knack for creating characters that black audiences would recognize and savor, and for discovering young and emerging talent. Critics sometimes complained that he was too heavy-handed, or over-ambitious in scope. But his immersive stories about urban youth culture and its conflicts, while they were still fresh and volatile—a legacy of his early exposure to the Black Arts Movement—resonated with the hip-hop generation, which either flocked to his movies or bootlegged them. And he never forgot the time his mother took him to see Cooley High, directed by Michael Schultz. A slice-of-life story that centers on a group of rambunctious black teenagers from the midwest, it’s touching and funny—at least until the end, when one of the boys is beaten to death. “It’s such a good movie,” his mom said, when Singleton asked why she was crying. That got him thinking, if he ever made movies he had to induce the audience to feel like they’re watching real life.

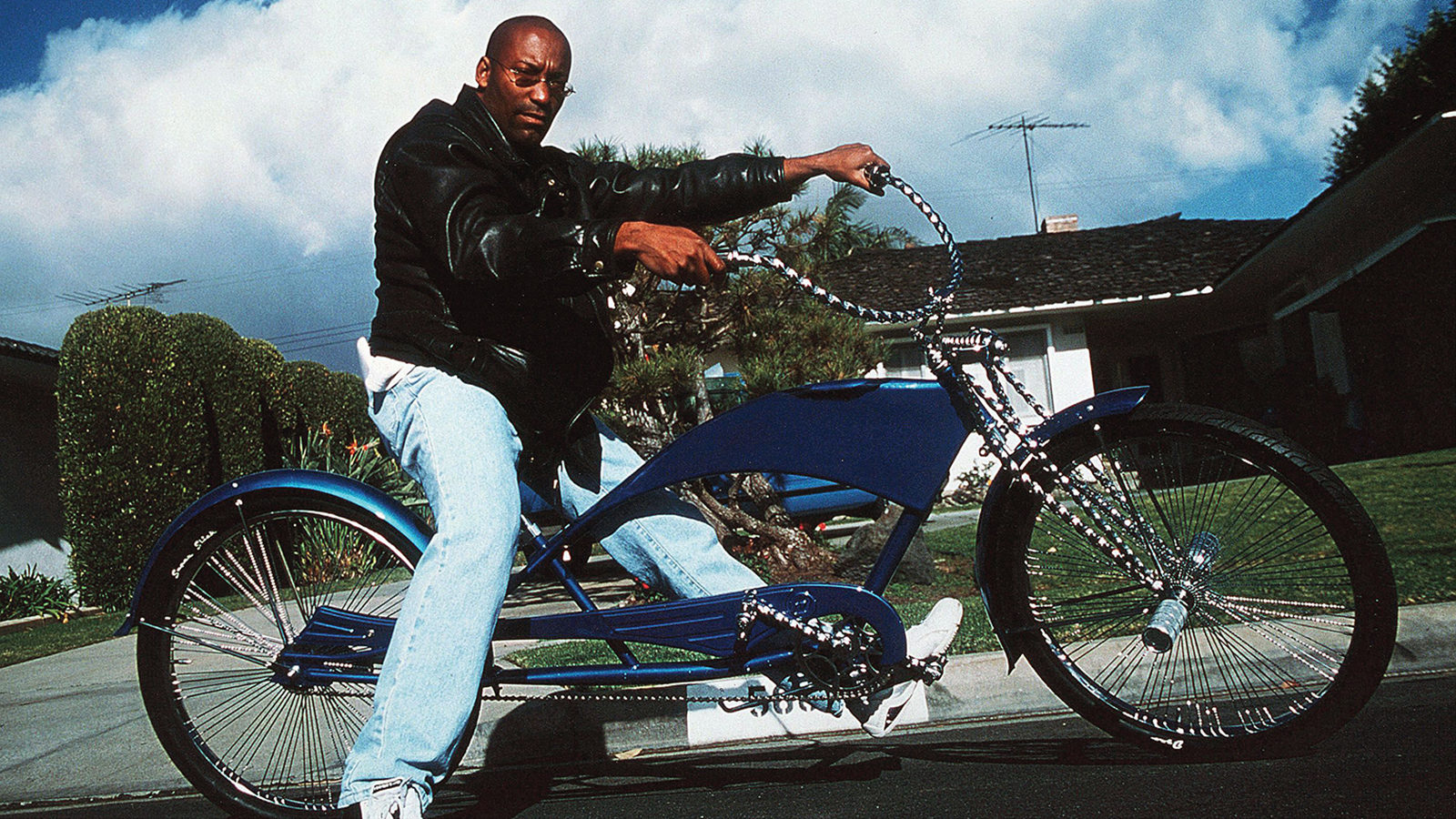

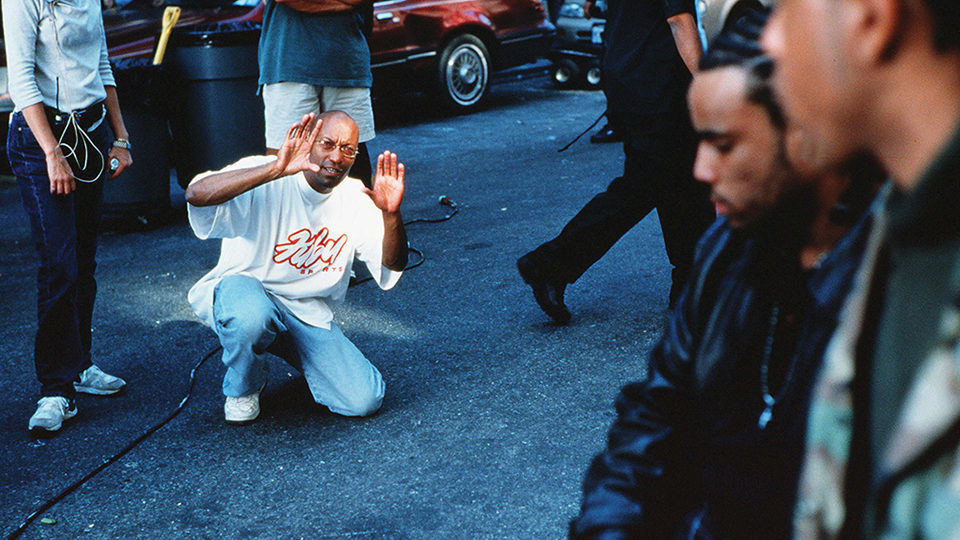

John Singleton on the set of Shaft (2000) Photo by Eli Reed/Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

The constant student, Singleton also spent a good deal of his life immersed in cinema. As a kid, he watched blaxploitation movies from his apartment window which overlooked a drive-in theater; a setting he later used for the opening sequence in Poetic Justice, his urban romance with Janet Jackson and Tupac Shakur. One of his favorite genres was the western, whose underlying moral currents he embraced in Four Brothers, which is set in wintry Detroit, where a group of adopted sons avenge their mother’s brutal murder. And very few people know that Boyz N the Hood was in some ways a stealth homage to Stand by Me, one of Singleton’s favorite movies growing up; both coming-of-age stories feature adolescents encountering a dead body. He wasn’t above devouring the big-budget special-effects fantasies that are Hollywood’s specialty, but Singleton was also inspired by cinema gods like Akira Kurosawa, “whose films dealt with feudal Japan,” as well as Med Hondo, a boundary-pushing founding father of African cinema.

Singleton never claimed to be a great visual stylist, which is not to say that he was an unimaginative director. He had tremendous instincts for creating atmosphere and environment. Perhaps responding to the layered sound design in Boyz N the Hood, with its whirling surveillance copters and random crackle of gunfire, several people walking out of the theater actually wondered if it was a documentary. Then there’s the moment in the film when a character lies dying from a shotgun blast and Singleton strips out the sound altogether, a technique he later repeated in Higher Learning, that is used to shocking effect. Several of his movies also feature interlocking stories that lead to impressive editing sequences.

But mostly Singleton liked to keep the focus on his characters. He wasn’t much for bravura camerawork or gimmicks that called attention to themselves. Everything was done in service of the story. What he cared about most as a storyteller was “emotional resonance.” When it comes to violence, as Pauline Kael once said, there are two types of moviemakers; those who use it as a turn-on and those who sensitize you to what violence does to its victims. Singleton was clearly in the latter group. The characters in his films are often permanently marked by violence. It affects not only their behavior and thinking, but choices in life.

In Poetic Justice, which he wrote over the span of two weeks, Jackson plays a beautician, who is traumatized from watching her boyfriend’s murder and has to learn to love again when she meets Shakur’s postal worker. With Baby Boy, which looks at how black men are infantilized by society, the young, weed-smoking hustler (Tyrese Gibson), who has babies with different women, tells his girlfriend (Taraji P. Henson) he wanted her to have their child because he thought he might get shot out in the streets. “I wanted a piece of me to still be here, even if I was gone,” he says. Today, Baby Boy is considered one of Singleton’s most personal movies and, together with Boyz N the Hood and Poetic Justice, a worthy conclusion to his “hood trilogy.”

One of the pleasures of watching Singleton’s work is the naturalistic performances. Even the supporting characters, like Jeffrey Wright’s Dominican drug lord in Shaft, whom The New York Times said talks as if he’s “burned the roof of his mouth,” are individually etched so we feel we understand their motivations and become invested in what happens to them as the story develops. Like all good directors, Singleton saw aspects of himself and his friends in characters, and could tell if someone was lying. When he auditioned Michael Rapaport for the role of a misfit college freshman who joins a neo-Nazi outfit in the ensemble drama Higher Learning, which follows an incoming class at an elite private university, Singleton had the actor read a racist diatribe in front of an audience of Muslims. Singleton told him: “C’mon, let’s see how good of an actor you are.” Singleton asked tough questions of his characters, too. In another scene from Higher Learning, the militant black student Fudge (Ice Cube) wants to know if Malik (Omar Epps), a black athlete at the school, would stand for the national anthem at a football game, knowing the country’s system of racism and oppression. (Singleton wrote that scene a decade before Colin Kaepernick began kneeling at NFL games to raise awareness of social injustice. How’s that for prescience?)

Singleton’s impact, of course, went beyond his ability to shape minds. “Probably the least known and most heroic thing about Boyz N the Hood, is that the lives of so many people who worked on the production were changed because of it,” said Boyz N the Hood producer Steve Nicolaides. Throughout his career, Singleton made a point of hiring blacks and other minorities behind the scenes. On his first feature alone, as many as 30 people in the nearly all-black crew earned union cards from the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employers.

After such historic beginnings, Singleton for a while believed each movie needed to be more serious than the last. But in order for him to grow as a director, he knew he had to prove he could do more than just hip, urban fare, so through most of his later years he pursued commercial projects, including Shaft and 2 Fast 2 Furious. The Furious sequel gave him the biggest hit of his career, grossing $236 million, a record at the time for black directors. His final and least identifiably Singleton-esque movie, Abduction, a modestly budgeted action thriller starring Taylor Lautner as a troubled, upper-middle-class kid who discovers his picture on a missing children’s website, fizzled at the box office in 2011.

In one of our last interviews, while driving through South Central, Singleton told me about how he’d been itching to return to small, vibrant movies, with a diverse cast and crew that had his back. He hated Hollywood’s recent penchant for making “black versions of white films” and talked about wanting to see more stories rooted in black culture. “Man, I gotta get back to work,” he said. “I gotta do something for the folks.”

There’s no denying that Singleton has done that, and more.

Closer Look: A retrospective of John Singleton’s work runs September 13 to 20 at BAM.

This is a longer version of the article that appears in print in the September-October 2019 issue of Film Comment.

Craigh Barboza is a journalist, professor at New York University, and editor of the book John Singleton: Interviews.