The Straight Story

When I was young, the words “plot” and “story” and “narrative” were dirty words in downtown New York cinema circles—so dirty that they became interchangeable. Stories were bad habits, “19th-century theatrical conventions” (the conventions in question stretched much further back in time than the 19th-century, but no matter). Narrative was, on the one hand, an additive that polluted pure cinema; on the other hand, the Trojan Horse that concealed the secret weapon of “ideology,” undermining us in ways that only those who read the right books could even begin to understand. Plots were to be dismissed, reviled, feared, seen through, exposed, but they were never to be taken seriously.

This was a matter of intellectual fashion, driven by the fashion of the greater culture. The Eighties was a lengthy season of compulsive judgmentalism, now married in my memory with overcast days in a cavernously quiet Soho, screenings of 16mm prints in fluorescent-lit classrooms with scuffed floors and flaking acoustic tile ceilings, film containers covered with uncountable generations of white tape and permanent markings, and images clicking and flickering in and out of focus on the glass screens of gun-metal green and gray flatbeds. Certain names and phrases and references were invoked so regularly that one had the impression of Benedictine monks chanting morning prayers—“the notion of . . . Barthes wrote . . . imaginary Signifier . . . Heath . . . mirror phase . . . Brechtian…” And Marx and Freud, always invoked together, like a law firm (“I like Marx and Freud just fine,” a professor told me, “but why they have to be synthesized is beyond me”). Everyone but P. Adams Sitney dressed in flannel shirts, corduroys, and work shoes, artists-as-workers. I remember Hollis Frampton, dressed accordingly, sitting on a table and chain- smoking extra-long cigarettes as he not-so-gently chided Sitney for thinking that “everything is a story.”

There appeared to be multiple levels of moral seriousness to traverse, not unlike the spheres of heaven in The Divine Comedy. Commercial movies, running the gamut from Alan Alda to Stanley Kubrick, were scorned by the people that frequented art houses, art cinema was scorned in turn by those that restricted their viewing to the “genuinely” (as opposed to allegedly) challenging cinema of Godard and Straub and Huillet, which was in turn scorned by the experimental cinema world where the lovers of the merely beautiful films of Anger or Brakhage were dismissed by those that had received the ground-zero storyless purity of Peter Gidal or Tony Conrad’s unprojectable pickled films.

A younger acquaintance, too young to have lived through this moment within a moment within a moment, referred to it as “the days of unpleasure.” But finally, there was a kind of infantile satisfaction in the invocations of all these names and theories and the sense of instant mastery they seemed to bestow upon us, and in the reflexive choral distrust of everything under the sun, cinematic or otherwise, in the pursuit of untrammeled and unpolluted Edenic consciousness. But somehow, maybe because it was such an easy target, Exhibit A in the case against The World was always Narrative. The fact that all of the above was set within a greater master narrative that bore an uncanny resemblance to Invasion of the Body Snatchers (and anticipated Carpenter’s They Live, in which the heroes can “see through” the surface to the corrupt essence) went unremarked at the time. The Pod of Ideology could be hidden anywhere at all—under the bed, within our own minds, or within those things they called stories and characters, the ones with which we identified… and to which we surrendered. “Oh, you were moved by the story and the characters? How quaint. Did you vote for Reagan?”

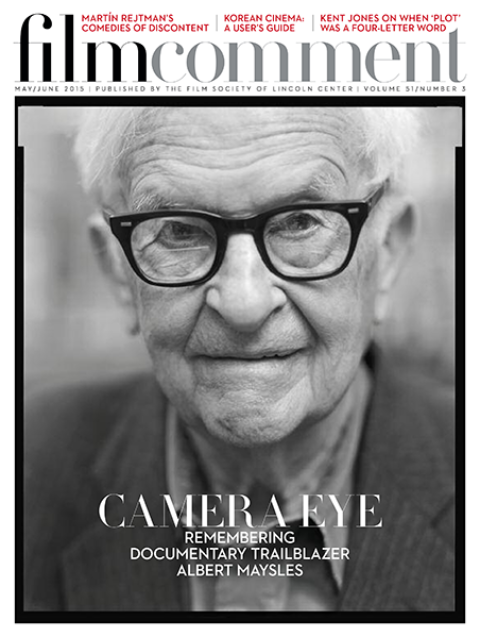

To continue reading this article, purchase the May/June 2015 issue.