Review: The Skin I Live In

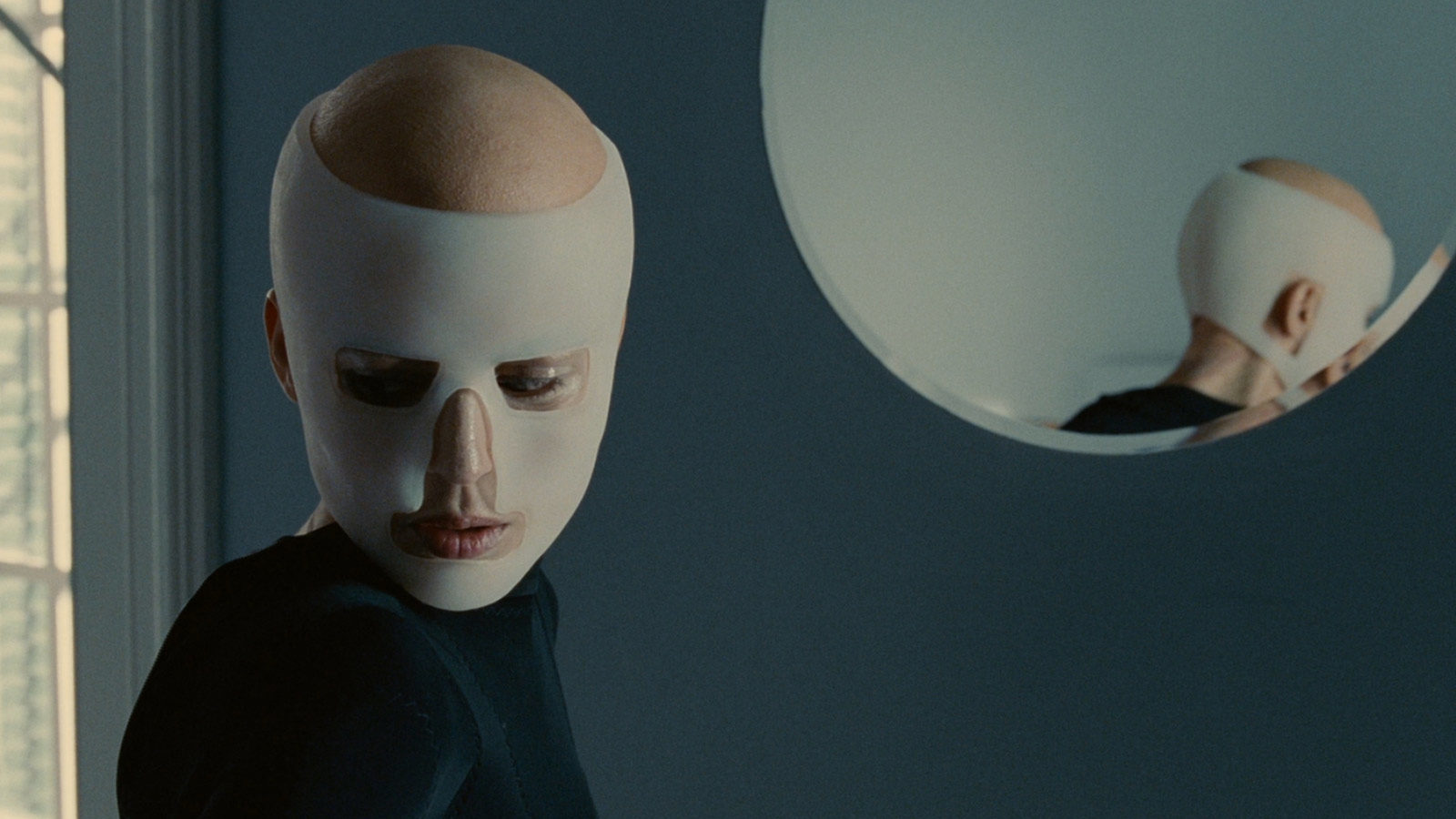

Everything made by Pedro Almodóvar seems to have been developed from the outside in: surfaces yield psychology, decor becomes depth, kitsch proves porous, a parade of pop props dimpled with wells of violently conflicted feelings and frustrated lusts. Seen through this lens, The Skin I Live In, based on Thierry Jonquet’s 1995 novel Tarantula, can be read as a work of perfect unity between its filmmaker’s MO and its fabulous premise. Afflicted by grief over the death of his wife and filled with rage over the rape of his psychically frail daughter—emotions that become perilously conflated as he plots his revenge—Toledo plastic surgeon and mad scientist Robert Ledgard sequesters an unwitting subject in his country home’s high-tech gothic laboratory and sets out to see if the interior self can be redetermined through the complete transformation of the exterior.

An uneasy forecast of looming advances in posthuman sciences, an extravagant extrapolation of Eyes Without a Face, and a fresh opportunity for Almodóvar to fix his unapologetically (queer) male gaze on more immaculate female flesh, The Skin I Live In embodies a rather studied sort of perversion that nonetheless resonates with Almodóvar’s evolving concerns in interesting ways. It returns to the family as a source of torment, consolation, and self-knowledge; it wrestles with anxieties about aging; it depicts the persistence of religious thinking in an increasingly secular world; and its most significant twist speaks to fantasies about gender appropriation and its pros and cons.

The film’s lengthy, flashback-heavy, deliriously knotted second act pushes Almodóvar’s predilection for complicated backstory, already straining in Broken Embraces, well past breaking point—the film’s wisp of a final scene suggests nothing so much as exhaustion. For such a provocative tale, the narrative is oddly tidy: every action taken by every major character in The Skin I Live In is provided with a clearly explained motivation. But a set of motives isn’t the same thing as a coherent character, and the film’s remarkable cast—among them Marisa Paredes, the utterly valiant Elena Anaya, and Antonio Banderas, reunited with Almodóvar for the first time since 1990’s Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, and the actor’s subsequent defection to Hollywood to become a willing embodiment of its laziest Latin stereotypes—are given precious little room to imbue their roles with nuance or ambiguity. So your engagement with this film will probably depend on your willingness to bask in its intricate designs, both narrative and decorative, in lieu of characters you can truly care about.

For my money, those designs are enough. I sometimes get the impression that we can divide Almodóvar’s audience into those who take pleasure in seeing how each new splendidly crafted film contributes to the oeuvre and those who see them as mere rearrangements of past glories, the work of an overindulged, self-conscious, fully domesticated enfant terrible and certified “master”—not to mention the emblem of an entire national cinema—resting on his laurels (it isn’t just his interest in flesh that links Almodóvar to David Cronenberg). Both perspectives are valid, I suppose, but I insist that the former is more generous and more satisfying. Almodóvar has a body of work as rigorously personal as any out there, and, even with its flaws, he wears this latest Skin rather well. In its best, creepiest moments, the film certainly got under mine.