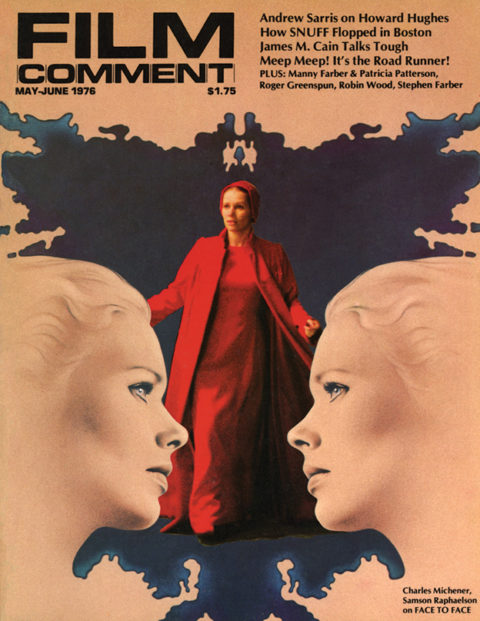

The Power & the Gory

Taxi Driver has a lot of negative aspects, but it would be silly to shrug off its baroque visuals and its high-class actor, Robert De Niro, whose acting range is always underscored by a personal dignity. He’s very good at wild manic scenes and better at poignant introversion: a man watching TV in a trance and eating while not looking at his food, or giving the sense of tense repression. Every scene combines the frantic and the still, almost simultaneously. The film has a good sense of modern paralysis, people flailing about energetically but not moving an inch (“twelve hours of driving a taxi and I still can’t sleep”). The visuals are almost constantly bold, covering a scene from all angles; a scene like the transaction of guns, even the pimp-cabbie verbal duels (in which Michael Chapman’s funky but somewhat slick photography is nearly static), are interesting scenes for the odd way the nearly catatonic cab driver (De Niro) is at an angle to some juicy spielist. He’s hypnotized and puzzled by Harvey Keitel’s razzle-dazzle pimp act. The queer oblique positionings of the scene, buzzing with star-turn acting, reveal a subtle insight: when any person feels tipped off-balance by ridicule, it often has a paralyzing effect. De Niro’s uneducated taxi driver freezes on the spot, not quite sure whether Sport, a big smile, is putting him down. He keeps saying “but I’m not a cop” as he gets the nice quality of a literal-minded person not knowing how to react to a hipster.

De Niro’s Travis Bickle, wanting to be “a person like other people”—to be a pair with the wondrous purity of his political campaigner blonde (Cybill Shepherd)—joins Alice Hyatt and Mean Streets’s always-repenting Charlie in Martin Scorsese’s angst oeuvre. His movies are about youth’s dreams squelched by the adult verities , the charismatic fullness of a jungle-cat punk (Keitel, trapped in Sport’s coded character), a feisty twelve-year-old whore (Jodie Foster, who has the shiny complexion, hair, and bright eyes of neither lower East Side nor a baby prostitute), a vulgar and good-natured cabbie (Peter Boyle, who like a Thirties character actor, tells Manhattan versions of tall tales to his buddies at the Belmore Cafeteria).

The apprehension about an eager-messy world is transmitted through a saucing technique in which Scorsese’s unique effect is the number of optical moves that are made in a tight space, seldom using a character’s point of view for his camera position. He has a romantic appreciation for Life which remembers an actor’s best moves and generously supplies the time for full-scale exposition. With its nervous-generous hoopla of techniques (including the tic of flicking suddenly to a ceiling shot directly down on a seduction, gun sale, or bloodbath episode), almost every moment of a lumpen figure’s hellish career has an assaulting quality, like a gnat banging suicidally against the light fixture.

When sensing danger to their young, small groundbirds with brains go off on a diversionary path, pretending to have a broken wing; in a pure case of bird theater, the female limps away from her nest to divert the attacker from her young; as the stalking fox or coyote gets close, the pretend invalid simply takes off. Just as diversionary to the always-interesting visuals as the pounding, illustrative music which grinds you, are the spike words which stud the Taxi Driver soundtrack. “Pussy” and “fuck” have never been harvested so often; the black race is mauled by verbal inventions spoken with elaborate pizzazz styling, “a regulah fucking Mau Mau land down there.”

One showy stopper seems a blue landmark for the R-rated movie. The pimp Sport, who is dressed with more mannerisms and gingerbread than an X-mas tree, is talking about his teen-aged bankbook Iris: “If I wanted to save money, I wouldn’t fuck her, man. Because she’s only twelve years old. You’ve never had a pussy like that. You’ll be back here all the time. You can do anything with her you want. You can come in her face, you can put it in her ass, she’ll get your cock so hard, you won’t believe it man.” Lots of things in Taxi Driver are diversions keeping the audience’s mind from the fact that it’s not getting the Promised Land: the inner workings of a repressed, ignorant fantasist, the mind of a baby whore, the experience of being a taxi driver twelve hours a day in the incredible New York street noise and jostle.

The movie starts a lot of material and then abruptly cuts it off, giving the sense that much of Bickle’s life, particularly his cab work, is reposing on the editing floor. No other Checker cab seems to be operating at night in Manhattan except De Niro’s cab, which never stalls, needs gas, or runs into the delays and quick decisions which are the cabbie existence norm. New York street noise is replaced by a writhing, intense Bernard Herrmann music track, saxophones and a pulled-taffy Muzak sound that almost buries the visuals. The hero’s taxi is mostly seen in abstract effects pulling up or taking off, the windows awash with ingeniously engineered colored lights; in one quick spray of inserts, there is a rhythm series of the same stop light, seen close by a camera crew that must have been stop-light high at midnight with its equipment almost hugging the light fixture. With its nearly abstract shots of the cab slowing moving like the Jaws shark through liquidy situations, the use of lush-soft, often reddish lighting for the effect of New York’s street jungle, and a floating camera style that finds funny angles of perception, the movie is filled with a spooky, exploratory beat.

Par for a Scorsese film is the jamming of styles: Fritz Lang expressionism, Bresson’s distanced realism, and Corman’s low-budget horrifics. After making a quotation, using the refracted light effects that appeared in so many Sixties European films, the movie adds one more shot inside the slick action. De Niro’s cab almost collides with the two child-whores-just as Janet Leigh’s fearful Psycho thief nearly overruns the man from whom she’s stolen a bundle- but in this film a long tracking shot is added to the gimp effect. When De Niro stares at his Alka Seltzer glass, there is a tiny sneak zoom into the bubbling water, which adds one more shot to Godard’s rapidly-spoken philosophizing in Two or Three Things in which the camera frames the coffee cup from above.

Basing its tortured hackie hero vaguely on the pasty-faced Arthur Bremer, who, frustrated in his six attempts to kill Nixon, settled on maiming George Wallace for life, Taxi Driver not only waters down the unforgettable (to anyone who’s read his diary) Bremer, but goes for traditional plot sentimentality. Bremer, as he comes across in his diaries, was mad every second, in every sentence, whereas the Bickle character goes in and out of normality as the Star System orders. The Number One theme in the Arthur Bremer diary is I Want to Be A Star. Having dropped this obsession as motivation, the movie falls into a lot of motivational problems, displacing the limelight urge into more Freudian areas (like sexual frustration) and into religious theories (like ritual self-purification). The star or celebrity obsession is a Seventies fact-the main thing that drives people these days compared to the dated springboards in Paul Schrader’s script. Instead of Bremer’s media dream, getting his name into the New York Times headlines, this script is set on pulp conventions: a guy turns killer because the girl of his dreams rejects him. The girl of his dreams, a squeaky-clean WASP princess, is yet another cliche assumption: that the outsiders of the world are yearning to connect to the symbols of well-washed middle-class gentility.

Busily trying to turn pulp into myth, the movie runs into all kinds of plot impossibles:

- A shy guy converts himself into a brutal killer after scenes in which he is a smart-ass with an FBI agent, a near matinee idol with his Miss Finishing School, and an unsophisticated, normal Lindbergh type with a teen prostitute. The latter girl similarly goes from street-hardened and cynical to open and cheerful, well-nourished and unscarred, in one twelve-hour time interval.

- The cabbie, after having readied himself with push-ups, chin-ups, burning dead flowers, and many hours of target practice, guns down a black thief in a Spanish deli. The brutality, which is extended by the store-owner golfing the victim’s corpse with a crowbar, is never touched by the police.

- A taxi driver who’s slaughtered three people, been spotted twice by the FBI, and has enough unlicensed artillery strapped to his body to kill a platoon, is hailed as a liberating hero by the New York press.

- A Secret Service platoon, grouped around a rather minor campaign speech on Columbus Circle, fails to spot and apprehend a fantastic apparition: a madly grinning young man who is wearing an oversized jacket on a summer day, sunglasses, and has his head shaved like a Mohawk brave, with a strip of carpeting for the remaining hair.

Although Taxi Driver is immeasurably more gritty, acrobatic, and zigzag-ging than the Jeremiah Johnson mythicizing of mountain men, the two films (one moves blandly forward on snow shoes, the other sets a grueling pace) are remarkably similar in their linear structure and ideology. Both are odes to Masculine Means in which a mysterious young man appears out of indistinct origins; learns the lore of survival warfare in a hostile land; after a heartbreak, lashes out in a murderous rampage; fades into a mythic haze. The lore Jeremiah-Travis learns has to do with manly self-reliance: the first learns to kill a bear, catch a fish barehanded; the “hackie in Hell” becomes a one-man commando unit. Both inhabit a world-an unpeopled wilderness and a callous jungle-where no one can be counted on for help. Women are the spurs to the climactic bloodbath: Jeremiah’s Indian wife is murdered, while Travis’s efficient blond tease rejects him, confirming him in his conviction that blood is the only solution.

The character of the Loner, which dominates American films from Philip Marlowe to Will Penny to Dirty Harry Callahan, has seldom been given such a double-sell treatment. The intense De Niro is sold as a misfit psychotic and, at the same time, a charismatic star who centers every shot and is given a prismatic detailing by a director who moves like crazy multiplying the effects of mythic glamour and down-to-earth feistiness in his star.

Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

From Michael Chapman’s opening camera shot of De Niro’s almond-shaped dark eyes filling a giant screen with a lizard-like stare, this movie’s aim is to turn a supposed nobody that no one sees into a glamorous giant who’s bigger than all New York. The presidential candidate, in his scenes with the lonely cabbie, is a vague, tissue-paper figure in the background, playing it safe. The cabbie, full of energy and verbally exhilarated, becomes movie dynamite with a speech about flushing New York down the toilet. While De Niro is dramatically lit and upshot in a powerful near-closeup, the earnest candidate (Leonard Harris) is pale and wooden in the back, caught off-guard by the verbal passion flooding in from the front seat. With its punching-ahead style, the movie typically explodes another Bickle persona at the spectator. Spreading out his features and smiling, De Niro suggests a slowwitted hick, which is at complete variance with the lean, intelligent face that he mostly wears as a cabbie. The yokel is really excited: “Everybody who comes in my cab is going to vote for you, Sir.”

Though De Niro rarely changes speed inside a scene, from scene to scene his Bickle figure is a whirligig with his IQ and sophistication shifting and sliding all over the place. At one moment, not knowing the meaning of the word “ moonlighting” or how to react to the “how s it hanging” query, at another he uses such words as “ venal,” “morbid self-attention,” and muses to himself: “I cannot continue this hollow empty fight.” At one moment, he is indistinguishable from Robert Ryan’s truculent Odds Against Tomorrow bigot; at another, he ravishes his blond princess like a new Cary Grant: he spreads his hands debonairly on her desk, looks into her eyes, and says “You are the most beautiful woman I have ever seen.” Later, asking the Wizard (Boyle) for advice, he becomes an inarticulate Jimmy Dean mumbler. The point isn’t that people don’t have many sides to their character, but that the filmmakers, going for hot and heavy scores, bend the material for spiking effects.

This changing hero is a deceptive opportunism hiding the movie’s polemics about superman and guns, plus a raft of prejudices that float through the two genres (vigilante and he-man loner) that are blended by the script. Every frame is awash with the prejudices of take-the-law- into-your-hands fare: the idea of sex as transaction, in which all the barely differentiated women are professional manipulators of men; black people as animalistic sinisters who get the sexual goodies and call the sexual shots; the lower class patronized as animals feeding on each other.

What’s really disgusting about Taxi Driver is not the multi-faced loner but the endless propaganda about the magic of guns. The movie’s pretty damn cunning mise-en-scene is a mystical genuflection to The Gun: what a .44 Magnum can do to woman’s face and pussy, the continuous way in which male brotherhood is asserted by one man pointing his pistol finger at the other and saying “pow.” If the male population isn’ t exchanging this payoff gesture, they’re addressing each other with “Hyah, Killer. How’s the killer, today.” The film’s funky, insinuatingly ripe surface comes from a steady litany of ‘ ‘I’ll kill you” shrieks, a collaging of sinister inserts, anal allusions, so many references to the sewer, “wiping the come and sometimes the blood off the seat,” a giant lotus of steam enveloping a cab like fumes from Hell. Each item of this melange is used as metaphor for the destructive blasting of a gun. Even the cab, moving forward with ominous slowness, is felt as either death machine or coffin.

“Isn’t that a honey, that’ll stop anything that moves” is the repellently glib remark of a traveling salesman, dealing in guns, dope, and Cadillacs. He looks like a choir boy turned bad, and is talking here about a .38 Smith and Wesson nickel-plated, snub-nosed Special in a tour de force scene in which the underground man is sold a $900 arsenal. Our salesman, earlier, on a .44 Magnum: “I could sell this to some jungle bunny in Harlem for $750 today, but I just deal high-quality goods to the right people.” This scene opens with a swift lower-case zest, when Bickle is picked up by a cab buddy and taken with the salesman to an anonymous hotel room. As the guns are taken out, one by one, the camera settles into a meticulous interweave that combines some of Vermeer’s patience for illuminating smallness (the rich dark handles, the bewitching highlights of a gun barrel displayed against soft black cloth) with the salesman’s fast talk, Bickle’s silent concentration on choosing his weapons, and a textbook of small sneak-moves of the camera going across furniture, shiny guns, and respectful hands.

De Niro, inscrutably going through a repertoire of gunman stances, seems directed to act a Bresson isolate: disclosing little of his interior, emphasizing the ballet of gestures (like the poacher laying down traps in Mouchette). The movie has entered a new stylized world; the spaces between people are calmer and the black hallucinatory street images have dropped away. The character is in a more methodical world of information and religious ritual; the mood is the one that prevails in Travis’s one-room sanctuary: no sheets, TV propped on a wooden crate, a printed admonishment “I Must Get Organazized” tacked to a wall incredibly layered with cheap, cracking enamel paint.

Seldom since John Ford’s epics of Joad and Lincoln in the 1939-40 period has there been such Oily, over-definition of the lower classes. How colorful these workers are: a one man compendium of champion jazz drummers studied for three minutes (”now Gene Krupa’s syncopated style”); or Keitel’s incredibly garish pimp, decked out with tight-muscled mannerisms, the weirdest clothing, an appetizing voice that tries to score on every word. One standout example of an over-detailed shtick: a snarling, aggressive guy who hires cabbies and overreacts wildly to Travis’s small attempt at a joke with a ferocious “Are you going to break my chops? . .. If you are, you can take it on the arches right now.” Twenty seconds later, he melts with brotherhood and warmth, learning they’re both ex-Marines. The spectator is asked to digest a lot, given an excess of muscle and colloquialism, but there is yet another small feistiness out of Breughel going on over the hiring boss’s shoulder. Behind him is a window in which two cabbies are gesticulating in another rich slice of street ham, starring Peter Boyle or his domed-forehead brother.

The movie relishes getting blacks off as malevolent debris that proliferates on the streets. Everywhere the cab moves there is a black marker representing the scummiest low point of city life. A muscular black walks through a barely noticing crowd on a narrow sidewalk; he’s muttering loudly ‘ ‘I’ll kill her, I’ll kill that bitch.” A gang of black teenagers bursts out of an alley hurling garbage at Travis’s Checker. Three little black kids torment a black whore, who, seeming used to such defiling, lashes back with her shoulder bag. There’ve been tons of media explication about the bigotry and sexism in Travis’s head.

The fact is that, unlike the unrelentingly presented worm in Dostoevski’s Underground Man , this handsome hackie is set up as lean and independent, an appealing innocent. The extent of his sexism and racism is hedged. While Travis stares at a night world of black pimps and whores, all the racial slurs come from fellow whites. In fact, Travis tries to pick up a mulatto candy seller in an interesting porno-theater scene. He tries to joke with this bored, rather pretty but definitely uninterested popcorn girl who’s reading a fan mag, and she calls the manager. De Niro, giving up quickly and furtively switching to buying candy, creates a telling poetic ambience ($1.87: “gimme some Chuckles . . . and some Jujus, they last longer . . . some popcorn and some Coke”).

There’s dubious indication that the cabbie is a woman-hater, but the film is a barrage of cheapened sex washing over a graceful nobody who is basically a receiver rather than a giver. It’s not Travis who talks about blowing a woman’s pussy with a .44 Magnum; nor is it Travis who speaks as the patently insincere voice-over in a porno flick (”Ooh, that’s a big one, I’d like some of that”); nor is Travis talking about a hot customer who changed panty hose on the Triboro Bridge.

Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

Taxi Driver is a half-half movie: half of it is a skimpy story line with muddled motivation about the way an undereducated misfit would act, and the other half is a clever, confusing, hypnotic sell. End to end, behind as well as in front of the camera, is the sense of propagandists talking about power, scoring, and territory. The movie’s ad campaign (the poster of De Niro as a looming presence, the interviews with crew members almost before the final mixing, the terrible schlock novel now sold in every supermarket which takes Bremer’s diary and Schrader’s script to an unbelievably trashy depth) is revelatory of what the filmmakers feel it takes to move, score, and hold your territory in a competitive USA society.

Reconstituting pulp is central to both the movie’s writing and filming, always juicing up or multiplying a cliche notion so that the familiar becomes exotically humorous. Pumping up cliches runs inevitably into moral problems. A scene that’s been grooved a thousand times on TV crime shows, not to mention late film noir like Hustle (a store heist recorded with the camera on an unexposed customer who then guns down the surprised marauder), is super-charged out of the cliche by showing the store-owner brutally beating up the black corpse. Are there any moviegoers left who aren’t fed up with personal reform through Atlas physical exercises? The hero suddenly stops “ mistreating his body,” goes into a regimen of musclebuilding, target practice, and health food. This situation is juiced up with a comedy scene that throws audiences in the aisles. Bickle, strapped up with his special equipment and guns, faces himself in the mirror: “You talkin’ to me, You Fuck! You must because I’m the only one here.” The sneering monologue refurbishes two or three cliches, it sneers at anyone who isn’t a gunsel or muscle boy, and puts a glamorous sanction, a good gunman seal of approval, on the movie’s future holocausts.

A chief mechanism of the script is power: how people either fit or don’t fit into the givens of their status, and the power they get from being Socially snug. Travis’s dream girl has power because she has a certain golden beauty and doesn’ t question or rebel against her face or her position as political campaigner. Various pimps are shown as editorialized icons of illegal power. The cabbies, more or less at peace with themselves, are glimpsed as a gang not fighting job or status. The movie shows the facts of being in or out. Everyone plays this power game but Travis-he can’ t figure what kind of game he wants to play. While this misfit moves toward his massacre in a Twelfth Street bordello, the movie’s heart is an ensemble of chesty people jockeying to score points. The script sets up a world where people constantly score off each other, releasing petty hostilities. Little Iris’s professional command: “You better get to it, Mister, because when that cigarette goes out, your time is up.” Some sexual invitation; the guy’s just payed $25 for Iris’s briskly dispensed time and at least ten smackers for the use of the beads and candle-filled room. The jittery pimp, a big grin, gestures off De Niro toward his fifteen-minute session: “Go ahead, go on, enjoy yourself, have fun.”

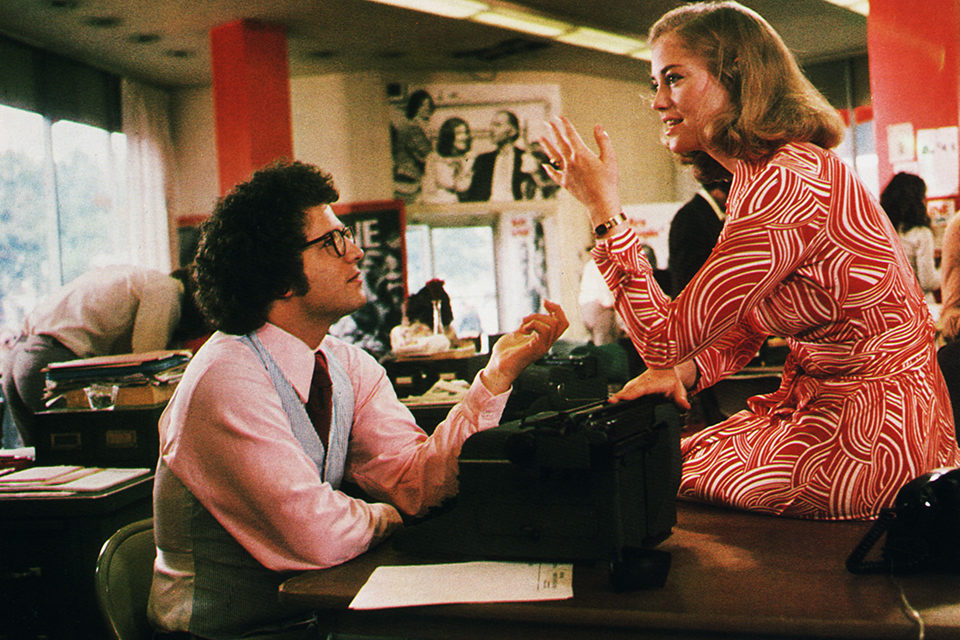

The importance of humor is one of the movie’s trumps, as well as one of its bad cards. When people try to jokingly tease De Niro, he can’t throw it back. He tries to joke with the cab employer and the guy explodes. Betsy doesn’t get his “ organazized” joke. This sealed-off guy’s problems with humor—his crestfallen, embarrassed, or shamed responses are always poetically right; and the movie is almost always good when it’s dealing with his communicative impotence. Each class here has its own way of trading quips. The slick, TV-influenced razzing between Betsy and Tom (Albert Brooks) is repellently smug; the tall-tale sex stories the taxi drivers trade are more inventive, and Peter Boyle’s timing (“Shoot, they don’t call me the Wiz for nothing . . . well, I’m not Bertrand Russell, I’m just a cabbie”) is tantalizing.

Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

Through the use of red- or brown-toned darkness and the feeling of closed space (in which, despite the sneak camera moves, down shots, and weird angles, the focus is narrowly on players), the movie is often zeroed in to womb situations. The spectator is focused on some territorial claim. Tom, the indispensable hack, is upset about Travis’s entering the campaign quarters, which is his turf. The hiring boss at the cab depot is immediately suspicious, all territorial muscle, when an unknown intrudes. When Bickle squires Betsy to a porno house, she makes it clear the skin place is not her turf, she’s a high class girl. A suffocating dance presses home the fact that Iris is Sport’s real estate. At times, the movie seems to be about worried landlords protecting their property. Perhaps the movie’s central speech is the Wizard’s: “You have to find your niche and fit into it. It’ll be awkward at first, but you’ll get used to it.” Travis, seldom relaxed in any territory except his animal-lair room, works his way through a violent landscape which is curiously pluralist in its technique. One frame isn’t promoted over another, there is no favored composition (as there is in every Bresson film), there are constant changes of style, pace, and arrangement. The only constant is that the hero, in crowds or alone, in broad daylight or total darkness, appears to be alone in a dense funnel or cave of space.

All the elements in Taxi Driver-from the steam which billows from street openings enveloping the screen to the incredible army of technicians who had to engineer the fortissimo reverse tracking shot through the bordello’s bloody hallway-are aggressively self-assertive. Taxi Driver is always asserting the power of playing both sides of the box-office dollar: obeisance to the box-office provens, such as concluding on a ten-minute massacre, a sex motive, good guys vs. bad-guys violence, and casting the obviously charismatic De Niro to play a psychotic, racist nobody. (Some nobody-like casting another neurotic-role star, Helmut Berger, to impersonate Kaspar Hauser. “OK Helmut, look as though you had no education at all. Pretend you’re not handsome, no social graces at all.”) On the other coin side, it’s ravishing the auteur box of Sixties best scenes, from Hitchcock’s reverse track down a staircase from the Frenzy brutality, through Godard’s handwriting gig flashed across the entire screen, to several Mike Snow inventions (the slow Wavelength zoom into a close look at the graphics pinned on a beaten plaster wall, and the reprise of double and triple exposures that ends Back and Forth) .

One thing that stands out is that many of the new demons in Hollywood are flourishing inside a Bastardism. They are still deep within the Industry and its Star-Genre hypocrisies, and at the same time they have been indelibly touched by the process-oriented innovations which began with Breathless. The result: a new hybrid film that crosses a mythicized genre film with a mushroomed aestheticism which (while skimping the material of psychosis, prostitution, taxi work, the celebrity urge) shows a new sophistication about pace, camera, and organizing. It’s revealing that the Taxi Driver political scenes—from the office comedy between Shepherd and Albert Brooks to the speech in Columbus Circle—are very bland and stock. Why should a movie that is so anti-American go so dull when it hits a glib phony populist running for President? Busy building the old loner character who never asks for anything, NYC as a dead sea of garbage in the Fritz Lang manner, the girl-boy gag charm from the Screwball era, the crew’s mind comes up empty on the movie’s one area that rises above the working-class milieu, that’s free of the city-as-a-sewer metaphor. Empty politics are more of a US tragedy than the lone assassin. Why is all the attention going toward the De Niro charm as a displaced country boy who is out of his depth, unless the authors are obsessed by Industry staples?

How did they get those colored shapes of light to swim around the nighttime heads of De Niro and his passengers? Was that overhead shot, of De Niro’s hand and arm sweeping over the blond campaigner’s cluttered desk, shot at the same time as their conversation? In the final moments, the furtive panic of Travis, glancing to right and left, washes into a long corridor of multilayered street impressions. When were the decisions made to go for slow motion in this tumultuous irresolution that ends Taxi Driver? Did the final track out of the death chamber move under or above the ceiling’s paper lantern? And what about De Niro’s succulent scene (“Are you talking to me? . . . you must be talking to me . . . I’m the only one in the room”) in which the mole usually on his right cheek shows up on the left cheek? The amount of twisting questions that are thrown at a spectator highlights its director’s boldness on intricate visuals.

Taxi Driver is yet another glorification of the hood as a glamorous energy force; at least its director has injected a rare lower-case vision (the Godfather movies being upper-case filmmaking) into the threatening congested darkness.

Scorsese is clearly an original force in films. Some of the best things come from the sense that the director and lead actor know what it is “to be poor,” to live in a NY walk-up, the tormenting lethargy of depression. The overhead shots of De Niro lying on his grimy cot, fully dressed, totally riddled with discomfort, lap the hollowness of the room that doesn’t nourish its owner with Travis’s desperation. Taxi Driver is actually a Tale of Two Cities: the old Hollywood and the new Paris of Bresson-Rivette-Godard. More importantly, its immoral posture on the subject of blacks, male supremacy, guns, women, subverts believability at every moment in favor of the crucial decal image that floats around the world-a lean, long-legged loner in cowboy boots who strides down the center of a city street, knowing he cuts a striking figure. This De Niro image, looming over his vague environment, is voiced everywhere in the script: “Around his eyes, in his gaunt cheeks, one can see the dark stains caused by a life of terror, emptiness, and loneliness.” The next line is great: “He seems to have wandered in from a land where it is always cold.