A friend mused aloud over a Carlton terrace Pernod: “The Martian school of poetry redefines and revitalizes our response to the familiar object and experiences of terrestrial life by portraying them as if from the viewpoint of another planet. Take the poet Craig Raine . . .” But then it started raining.

The Baby of Macon

Two hours later, splashing into the Palais des festivals for a celluloid warm-up, I was still thinking about what he said. If Martian poetry is an odd way of going about art, how about—Lights! Costumes! Action! —the 46th Cannes Film Festival? This was the weirdest French movie spree in years. For Martians gazing with fresh eyes on Earth, read the Present emergency-landing on the Past. We who came to learn about 1993 were shoved instead into lecture-shuttles going to 1893, 1793, 1493, 993. . . . Victorian New Zealand? Board Jane Campion’s The Piano. Medieval Italy? Pupi Avati’s Magnificat. Napoleonic Italy? The Tavianis’ Fiorile. Miracle-mad 17th century somewhere in Europe? Peter Greenaway’s The Baby of Macon.

Why this obsession with yesterdays at Cannes ’93? Maybe because it’s the shortest, most illuminating route to tomorrow. We knew something funny was being told us about Time and Space when we were all frogmarched off the beach on Day Two—I hadn’t even got my primer coat of suntan yet—to see Abel Ferrara’s Body Snatchers (aka The Siegel Has Re-Landed). And this was followed a few nights later by Wim Wenders’ Faraway, So Close!. Ferrara’s flick is all about the future landing on the present in a small U.S. Army base. Pod people from Outer Schlockland take over the cast and study/impersonate one cosmic community from the viewpoint of another. Wenders’ epic follow-up to Wings of Desire (165 minutes and every one counts) was also about—yes—beings from one dimension coming to earth to study and impersonate those from another. Now as we know from Commander L.P. Hartley of the Starship Go-Between, the past is a foreign planet. So the Cannes filmmakers who launched themselves from one gravity system—Now—to another—Then—were doing much the same as Wenders’ life-enhancing good angels (if their films were good) and Ferrara’s soul-numbing pod-colonizers (if they weren’t).

Of the good, Campion and Avati were the early standouts. From its first showing, The Piano looked the surest cinch for Golden Palm since Padre Padrone. Indeed, the shimmering primitivism and power to new-mint emotion echo the 1977 Taviani film; and like the Tavianis, the Australian director uses a geohistorical terra incognita—the remote New Zealand bush in the 19th century—as a way to explore the present through a sense-awakening encounter with the past.

The Piano

Campion’s beat is feminism, but of a thrillingly nonconformist sort. In Sweetie and An Angel at My Table, she gave us disturbed/dysfunctional heroines, women on the verge of a spiritual breakdown. But for them, as for The Piano’s mute, unmarried other from Scotland, Holly Hunter, who’s pushed into an arranged marriage with Antipodean colonist Sam Neill, an alienated vision is also an objectifying, truth-finding one. Hunter’s 19th century Miss, thrown onto what seems another planet, is given a shock education in Nature (jungly vistas), in Sex (gone-native neighbor Harvey Keitel), and in the untouchable sanctity of Art. Her beloved piano is first left abandoned on the seashore, then seized by Keitel and used as an amorous bargaining chip (he sells it back, one key per sexual favor), and finally thrown from the departure boat at Hunter’s wish, the last redundant ballast keeping her old life afloat.

Just as galvanic as the heroine’s clash with alien reality is the audience’s. We cross not just sea but a century. Campion, deconstructing the modern world by reconstructing a bygone one, unsettles all our “eternal verities” about sex, love, female identity by showing they’re not eternal at all. Other times, other truths. (Therefore, guard each advance we make.) In the disrupting process, Campion’s movie releases all the feral stylistics hinted at in her feature début, Sweetie. Early shots set in Scotland, plus literary voiceover, may threaten Masterpiece Theatre. But once our heroine is carried ashore in New Zealand—a black-dressed body borne above a dozen legs like a surf-borne spider—the past becomes more than just a foreign country. It becomes a wilderness, a bestiary, an Unpeaceable Kingdom. The Campion camera invents its own calligraphy. Shots swoop or arc like birds. Shots tell us that the human mind is a gateway to grace or chaos, as in the bizarre moment when the camera tracks in towards the heroine’s spinsterly hairknot and then rises up and onward into the anarchic forest.

The movie finds preposterous aesthetic rhymes, and each one works. The ribs of Hunter’s hoop skirt—portcullis to sex with Keitel—make harmony with the arching forest twigs she later crawls through in dismay and terror. A dog licks Sam Neill’s hand, producing a transferred shudder of disgust, as he spies on Keitel using his profaner tongue on Hunter. And there’s even a special, ancestral rhyme for movie buffs. Which of them, when Neill thwacks down on his wife’s pianistic hand with a nasty instrument, doesn’t see the ghost of James Mason smashing Ann Todd’s digits in The Seventh Veil? Footnote for certifiable film buffs: When Neill left New Zealand for his first Western acting role, it was James Mason who encouraged and recommended him.

The Piano

The Piano uses past and present in rhyme and counterpoint to create a fugue between the familiar and the far-off or farouche. Similar music is heard in the festival’s other period pix. Peter Greenaway’s The Baby of Macon, pastiching a 17th century mystery play, is a crazed chorale to the age of religious faith and (flipside) the cynical exploitation of superstition. Title character is a tot with miraculous powers toted round a French city by his “virgin” mother before both come to sticky ends. Stuffed (overstuffed) with Greenaway bric-a-brac—gold-and-scarlet décor, mile-high wigs, throngs of naked bodies, keening countertenors—the film still culture-shocks us with an age in which we come to see our own greeds and scams (and our attempts to gild or camouflage them) as in a Velázquez distorting mirror.

Avati’s Magnificat intercuts half a dozen 10th century stories on eternal themes; birth, death, sex, God. But the early-medieval setting gives them a fresh reverberance. The girl baptized into convent life, the royal courtesan giving birth, the grim work-round of an executioner: under a sky bright with religious belief and dark with the fears of Hell, the banal and momentous swap roles. Looking down on Planet Middle Ages from Planet Now, we wonder how death was regarded so casually or serenely, sex and sensuality with such fear and distrust.

These costume films stand modern sensibility in front of a Schüfftan “mirror.” Part of it seems to reflect the present—our own faces in an artwork our own time has created—and part to offer an unsilvered view through to the past. The mixture can be clumsy. Britain’s Chris Newby in Anchoress, another tale of religious faith in the age of peasants and pudding-bowl haircuts, wins the Great-Settings-But-Oh-God-They’ve-Opened-Their-Mouths award. Medieval Britain is photographed with a bleak, persuasive beauty worthy of Andrei Rublev, but the dialogue is Monty Python gone stale. Even the Taviani brothers in Fiorile begin to look a bit rent-a-period. Haven’t these cornfields, doublets, donkeys, and crumbly cathedrals been seen before? And the Tavs’ message for today, about the corrupting power of worldly wealth—do we really give it 10 out of 10 for originality?

Farewell My Concubine

By contrast, the treatment of history in Chen Kaige’s ambitious and powerful Farewell My Concubine focuses a multitude of questions. Here our time—space shuttle delivers us to bygone China, departure point for a trip through that country’s stations of political agony during the 20th century. Last time we did this trip, our guide was Bertolucci’s Last Emperor. Chen offers two Peking Opera singers (Leslie Cheung, Zhang Fengyi) hanging on to the emergency cord of their ancient art as China rattles through Japanese invasion, nationalist victory, Communist rebellion, Maoist dictatorship, and that ruthless bonfire of the vanities—the people went up in smoke along with their possessions—called the Cultural Revolution.

The funny thing about this three-hour historical fresco is that, for two hours it knocks out the eyes, mind, and senses, and then it gets knocked out itself by history. When wise enough to foreground the human story—the two heroes and their struggle to perfect their public craft and resolve their private jealousies (Cheung loves Zhang, Zhang loves courtesan Gong Li)—Chen Kaige creates a brilliant sounding-board both for the din of history and for our own thoughts on art and politics. But by Mao-time the captions begin to outnumber the scenes between. “China 1945,” “China 1948,” “China 1966. The Cultural Revolution,” “China 1977”—no no, stop the history lesson, we want to get off. Our three cunningly contrasted protagonists—He, She, and AC/DC—become littler more than interchangeable puppet-figures barking out prescribed responses of fear or defiance or grief.

The Martian school of moviemaking has one, and only one, simple rule: DON’T EDITORIALIZE. Allow the years their proper time, the characters their proper space, the unfamiliar to stay unfamiliar: at least until the past has spontaneously found the same frequency as the present, or the frequency on which Back Then makes the most interesting compare-and-contrast noises with Right Now.

The Puppetmaster

A couple of other Eastern films—Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s The Puppetmaster and Tian Zhuangzhuang’s Blue Kite—had a go at juggling time zones and counterpointing private lives with public events. Hou’s Taiwan film is a doorstopping domestic epic (two and a half hours) about a real-life puppet maestro, Li Tien Lu, who moonlighted as an actor in earlier Hou pix, and his longwinded troubles with family and history. Trouble is, none of the troubles seem like big ones. Or even very interesting ones.

Compare Blue Kite, wherein a three-generation family goes through the Maoist hells of persecution, rural exile, “criticism” (that is, peer pressure as a form of mental torture), and the brutal thought-policing of Mao’s Red Army. This film never stops to deliver a lecture. All the sobering horror is in the events and the characters’ reactions to them: caught by the camera’s delicate neorealist framings and its attention to minutiae of face or gesture.

Delicate or not, Blue Kite was enough to rattle today’s Chinese though police. They first stopped the director from completing the film in China—was postproduced in Japan by Tian’s associates, following his shot-by-shot instructions—and then he was denied a visa to attend the Cannes world premiere.

The Blue Kite

Blue Kite is a masterclass in letting a story find its own power without authorial pedagoguery. But “Don’t editorialize” is a hard lesson. In Faraway, So Close! even Wim Wenders—who, God knows, can have the patience of the East (see Kings of the Road, The State of Things)—panics a little in the face of the illimitable. This new movie is Wings of Desire 2. That is, Berlin angel Otto Sander takes his turn to follow Bruno Ganz to Earth and become human. Time, Memory, and Emotion are again the themes. But they don’t grow organically from the story as in Wings (1): they’re spelled out on the screechy blackboard of the new film’s voiceovers or neon-written alongside the showbiz metaphysics of the casting. Peter Falk (serial TV star as symbol of eternity); Willem Dafoe (Scorsese Christ flap-jacked into Wenders Devil) as the evil “Emit Flesti” (spell it backwards); Horst Buchholz as the arms-running Industrial Age baddie (Magnificent Seven + One, Two, Three = maleficent 13); and even Mikhail Gorbachev in scene one, receiving a hand on the shoulder from still-invisible Sander as he pens great Gorbyisms for posterity.

Wenders’ Martianism aims to answer the riddle of “What does it mean to be human?” by bringing an alien onlooker to Earth. The Christ parallels are patent. But so is the feeling that after Wings of Desire, where Peter Handke’s tougher cerebrations stiffened the script, Wenders has run out of ways to make mortality seem novel. Instead, in Faraway, So Close! it ends up seeming like a novel—Robert Ludlum or Ian Fleming, to boot—as the climax explodes in shootouts, hijacked boats, and a trapeze-artist heist of which all we can say is, It’s fun but is it art?

Abel Ferrara’s Body Snatchers—the third version of The Invasion of—is fun, and let’s call it art while no one’s looking. Ferrara was roughed up by some Cannes malcontents for taking the twice-told movie fable and surgically extracting its subtlety. The pod people taking over this U.S. Army base somewhere in Nowhere, Middle America, are telegraphic zombies with staring eyes and (when roused) raucous cries. When bodies are usurped, a spaghetti-ish infestation runs amok over the human faces. And the film’s climax, a merry hell of pursuit, death, and small kids thrown from helicopters, is subtle only by comparison with Driller Killer.

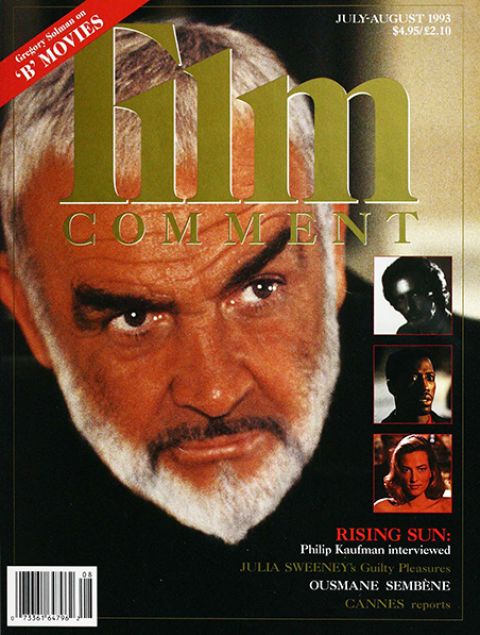

Body Snatchers

Yes, dear colleagues, but 1993 is not Don Siegel’s 1956 nor Phil Kaufman’s 1978. Today’s millennial stakes are higher. The first era was one of Eisenhowerian faux-serenity, when podpersons had to behave like Norman Rockwell to fit into small-town life. The second was circa Star Wars and CE3K, when things that came from Outer Space were supposed to be Nice. Today, apocalyptic nastiness is a movie norm, so a creepy initial setting—army base as seedbed for indoctrination and emotional automatism—must be outcreepied by the creatures. Body Snatchers gives the Martian school of cinema a nihilist twist by suggesting the space invaders see us not as brave and willful earthpersons who must be tamed, but as crawling, corruptible lifeforms pretty much like themselves.

Or—hold the Best Director prize—like the lifeforms in Mike Leigh’s Naked. Leigh’s latest is not so much a movie, more a microscope session in the insect lab. Placing on glass slides the seedy London dwellers who people his entropic underworld, with their grungy mating rituals, restless anomie, and babbling non sequiturs, Leigh then examines the effect on these folk of a human virus from Manchester. This is the film’s “hero,” played by David Thewlis (Best Actor prize) with a Doomsday wit and all-weather sarcasm. He first lays waste his ex-girlfriend’s shared apartment, verbally and sexually, and then mooches off to preach the End of the World to the midnight streetpeople.

Naked is bleak stuff even from the maker of Bleak Moments. But it provided Cannes’s cinema of alien perspectives with the perfect coup de grâce. Everyone here treats everyone else as creatures from another planet. Manchester could be Mars to London’s Earth; an articulate philosopher-bum could be an extraterrestrial to the dim-witted mental down-and-outs he meets on every streetcorner. No need to fantasize outsider’s viewpoints in order to redefine reality: we all end up using sign language to everyone else as we try to say “I come in peace” or “Take me to your leader.”

Naked

Cannes warmed to Leigh’s film, but then it would. The event is living proof of Leigh’s thesis. No sane person could be expected to make sense of anything or anyone here without days or weeks of practice. Even then, you can be stymied by the unexpected. How are you meant to react to a 40-foot inflatable Arnie Schwarzenegger standing in the bay moored to a barge? (He and his real-life alter ego were both in Cannes puffing Last Action Hero). Or to the sight of glamorous Liz Taylor sweeping in to scatter charisma and host $25,000-a-table AIDS benefit dinners? Or to snow falling where there ain’t no snow? This was white soapflakes billowing down from the Palais roof to celebrate Sly Stallone’s snowy comeback in Cliffhanger.

Above all, what does your average newcomer from Mars, Moon, or Earth make of the spectacle of ?,000 journalists brainstorming daily over ?,000 films as the countdown to who-won and who-didn’t-win begins? Me, I wouldn’t give a week’s supply of croissants to see a space alien’s reaction just to the critics charts in the (ever multiplying) festival mags. Some have stars and blobs. Others lovingly fractionate numbers—how do you decide on “3.2” out of 10 for Britain’s stretcher-case comedy Splitting Heirs? One mag even has crosses for bad and what look like walking chicken-feathers—one, two, three, four—for varying degrees of good. Eventually I was told that these are meant to represent palms. But not even a Martian would draw a palm like that.

As for the Golden Frond itself, it went ex aequo to The Piano and Farewell My Concubine; and Holly Hunter grabbed Best Actress. What is this? The world’s festival juries are finally meting out just and well-considered awards? I went straight home and tore up my application form for emigration to another planet.